Why Affordable Housing Is Not Really About Housing

Finding affordable housing was a huge problem in the U.S. even before the COVID-19 pandemic — and it’s growing worse by the day as the economic fallout of the crisis continues. Despite many attempts to solve persistent housing challenges, very few have been successful.

The crux of the problem is that wages have not kept pace with the rise in housing costs in recent years. The housing problem will persist if we continue to simply look at averages and call for more affordable housing to be built. Instead, we should look at the factors driving the affordability problem for those who are most affected. Doing so raises real questions about whether it is even possible to build housing cheap enough to make it affordable to low-income, single-parent families.

What makes housing unaffordable?

Housing prices typically reflect supply and demand in a city or region. Demand depends on people’s ability and willingness to pay rent and on how much housing is available. Supply is tied to local policies, the cost of constructing units, the cost of raw materials and even an area’s natural geography.

Although we often think of housing being unaffordable in areas where it is expensive to live, household income is also a key driver. Simply put, if you’re not making enough money, it can be as hard to make rent in Lansing, Michigan as it is in San Francisco.

How we study housing has a big influence on how we view these problems. Many studies define rent-burdened households as households spending 30 percent or more of their gross income on housing. This oversimplifies the issue. Not only does this calculation make it impossible to disentangle whether low housing supply or insufficient income is the problem, it does not identify the types of households most likely to face affordability problems.

For a more complete picture of what’s driving housing affordability problems, we examined the amount of affordable housing available in various metro areas.1 We did this by analyzing data from the 2018 IPUMS USA 1% survey, which offers a window into households in metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) across America. An MSA is a geographic area with at least one urbanized core of 50,000 or more people, including the core’s surrounding area.

Is there affordable housing for single parents?

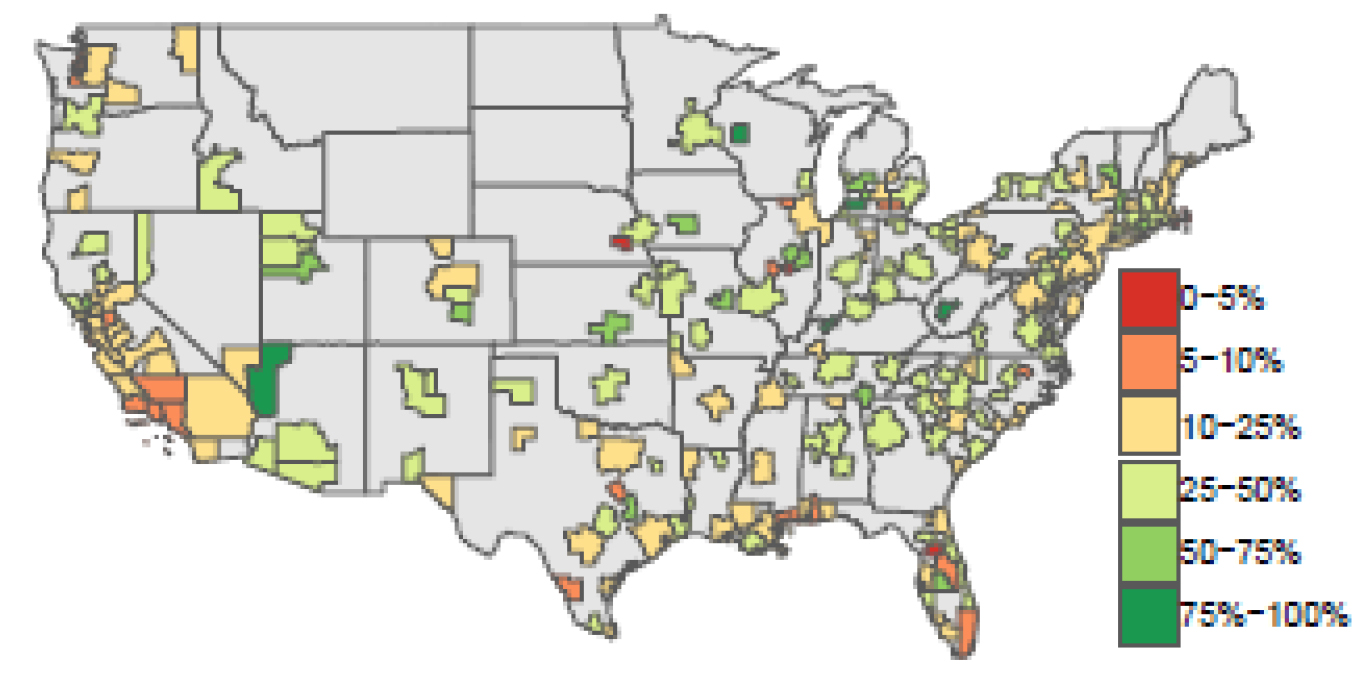

(a) At Median Income of Household Type in the MSA

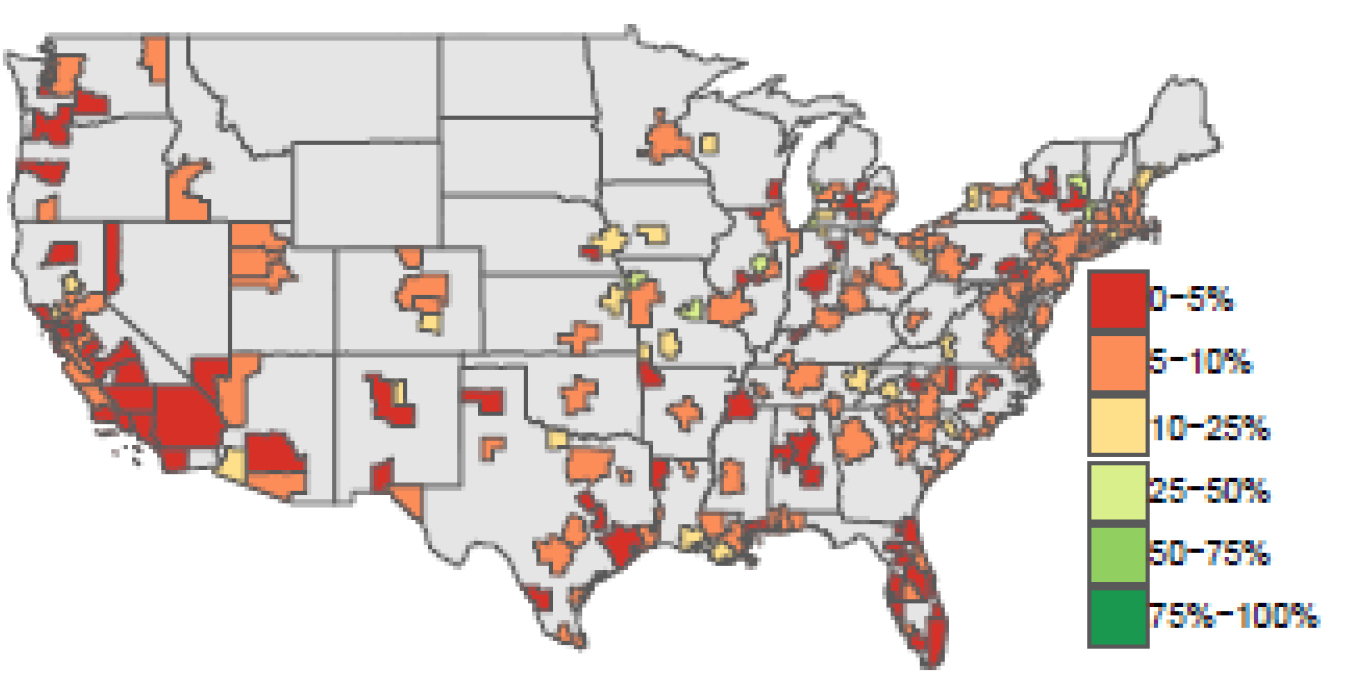

(b) At 30th Percentile of Income Distribution of Household Type in the MSA

Our analysis reveals that housing affordability differs dramatically by household type. In every U.S. city examined, at least half of housing units are affordable to two-parent households with the median income for that city. Only in coastal California do two-parent households face serious affordability problems. However, the picture changes dramatically for single parents. Less than 25 percent of the rental stock in most U.S. cities was affordable to single-parent households that make the median income for single-parent households in that city.

A surprising set of cities rose to the top as unaffordable. Of the top ten most unaffordable cities, only one was in California and two were in the Northeast, regions generally viewed as the priciest places to live. For single parents with one or two children, the most unaffordable MSAs with a population of at least 350,000 included Albuquerque, New Mexico; Santa Maria-Santa Barbara, California; Greensboro-High Point, North Carolina; Las Vegas, Nevada; and Lansing, Michigan. For many of the most unaffordable cities, housing costs were not particularly high, but incomes tended to be low.

Can’t we just build cheaper houses?

Many economists point to land-use restrictions and burdensome development approval processes as driving up the cost of housing and thus decreasing affordability. Although loosening regulatory barriers would certainly help, our analysis shows this alone would not be enough. This is because it’s almost impossible to build housing cheap enough to make it affordable.

Even in the least expensive cities, construction of multifamily housing costs $150,000 per unit, not counting the costs of land or soft development. Even if a developer only required a 5 percent return on capital, this would put the cost of a unit at over $1,000 a month. In the most unaffordable cities, rent would need to be less than $800 per month even if lower-income single-parent families spent 50 percent of their income on rent.

Another issue is that even if a city has adequate affordable housing available, it can be prohibitively expensive for low-income families to move, even if it’s just across town. Moving can mean losing important family or community ties that help families save money on childcare or that provide networks for jobs.

Where do we go from here?

Our study showed that in most of the country, housing affordability is a problem of low wages rather than housing supply. It is possible that focusing on building smaller units with less square footage per bedroom could help housing stay within reach for lower-income families. Tiny homes are unlikely to be a big part of the solution, given that they aren’t large enough for families to live in. New housing that is only slightly higher cost than existing stock could help slightly higher-income households move out of less expensive housing, making a greater number of affordable units available through a filtering-down process.

But we likely can’t solve the issue simply by building more housing alone. We need to consider a broader variety of creative solutions. For example, it may be fruitful to consider ways to help single-parent families share housing. A single parent with one child could potentially save 28 percent on rent by splitting a four-bedroom rental with another single parent. Such arrangements could also help families share household and childcare duties, reducing the burden on those households who have long faced some of the highest obstacles in our country. With today’s households buckling under the strains of a global pandemic, job loss and virtual schooling, housing affordability has never been more urgent.