We are living in an era of radical uncertainty. Escalating trade wars, multinational militarism and rapid environmental change are only some of the markers signaling heightened global risk and uncertainty. At its extremes, mounting geopolitical turmoil could jeopardize the institutional order established after World War II – an order that has nurtured the greatest expansion of wealth, economic development and democratization in human history and yielded an era of relative peace and progress.

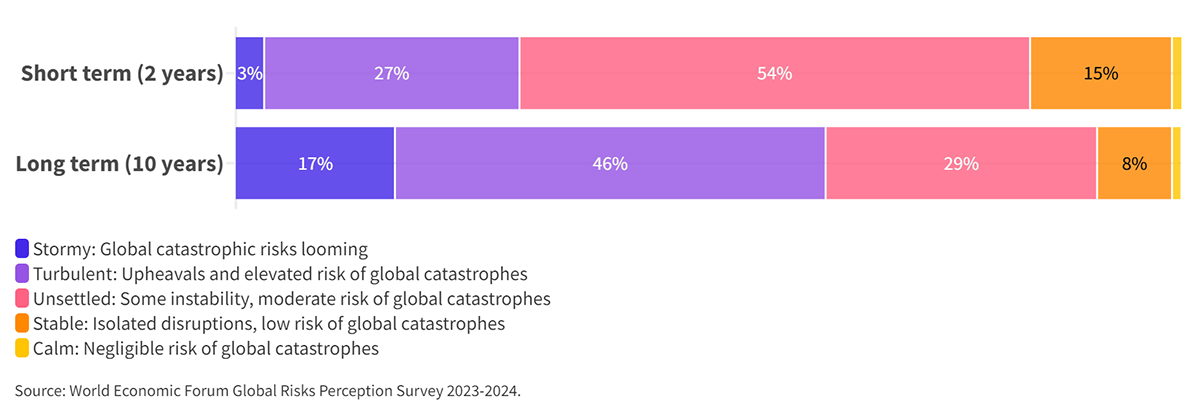

The Global Outlook: Stormy and Turbulent 1

Aside from direct military conflict or environmental cataclysm, the greatest threat to continued peace and prosperity is a loss of faith in the institutions that promote free trade and constrain global powers. Globalized trade has had many benefits, including lowering the costs of tradeable goods and services and spurring innovation and industrywide improvements. The increase in trade among nations has also brought industry, education, modern medicine and opportunity to poor, agrarian parts of the globe, boosting economic development and raising standards of living for billions of people.

Yet these rewards have not been distributed evenly. In too many places, the lion’s share of the spoils has gone to globalization’s “winners” while its “losers” have largely been left behind. Erecting trade barriers and torpedoing international partnerships, however, will only worsen inequities and risks sending civilization lurching toward a poorer, more violent and uncertain future. Buoyed by a rising populist tide, political movements aiming to wash away the international order only intensify the risk and uncertainty that we observe today.

From a business perspective, what should a firm do to build resilience to such radical uncertainty? What can a firm do?

Business Leaders Need to Consider Low-Probability, High-Impact Events

Companies require a degree of stability and assurance, not only to turn a profit but to function. As instability and uncertainty grow, the heads of private enterprises must plan for a more complicated set of possible contingencies. Yet radical uncertainty makes it exceedingly difficult to project future scenarios and assign probabilities to potential outcomes. This reality means that business leaders must give more thought to low-probability, high-impact events – not only because these tail risks are now more likely to occur but also, due to the complexity of global enterprise, because there are more of these potential pitfalls than ever before.

What is the likelihood of another global pandemic in the next few years? Greater than zero, that is for sure. In an election year, might there be radical regulatory shifts on the horizon? There certainly might be. As new tariffs take effect and protectionism is on the rise, what parts of a supply chain can be brought closer to home? How will global climate change impact resource constraints and migration patterns? It is among a business leader’s core responsibilities to pose and try to answer these sorts of vexing questions. Giving thought to potentialities is an important step in mitigating risk and uncertainty, and business heads unwilling to have conversations about challenging scenarios are courting their firm’s existential peril. Uncertainty, however, connotes the unknown – even the unknowable. So, how does a company prepare for something unspecified and undetermined?

Flexibility Is Key to Building Resiliency

Flexibility is key – not a panacea but a partial immunization against the unknown dangers that lie around the bend. To foster organizational resilience in an era of heightened uncertainty, firms must embed greater degrees of flexibility in their planning, structures and operations, and this flexibility is not free of cost. Firms pay a premium to build in degrees of freedom that allow them to adjust as real-world events unfold, and this price is an increasing part of the cost of doing business in the world today. These trade-offs demonstrate resiliency’s recurring costs, which, in a risk-filled world, reflect a choice between lower efficiency and total loss. Extra flexibility likely means some efficiency loss and a departure from “just in time,” or JIT, operations, which have become commonplace in many industries. In 2022, multiple surveys of business heads found that, in response to supply chain problems caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, about a third had moved away from JIT protocols and toward “just in case” practices, meaning holding more inventory on hand. The pandemic also changed norms and expectations in many industries around employees coming to work in the office, giving rise to a new work-from-home paradigm, which has proved to have staying power. There is evidence that firms that had the flexibility to allow employees to work from home retained more talent during the “great resignation,” when tens of millions of Americans changed jobs after the pandemic’s onset.

Doing Nothing Is Risky, Yet Risk-Reduction Must Be Balanced Against the Pursuit of Growth Opportunities

Not every company can afford to invest in resiliency measures commensurate with heightened levels of risk and uncertainty. It may not be possible for a multinational company with global operations to “near-shore” its supply chain or to safeguard itself from shifting political winds in every country where it does business. There is no way for a firm to bring risk down to zero or to become so flexible that it cannot break. An optimal goal is instead to create accurate risk profiles that reflect an entity’s actual operations, relationships and interactions and to plan accordingly. Perhaps you are head of global logistics for a shipping company that is seeking to reduce its environmental impact facing a near-term likelihood of tightening regulations. Or maybe you see opportunity in AI integration in many places in the firm’s operations, not only to increase operational efficiency, but to anticipate coming industrywide disruptions imposed by new technologies.

This level of thinking may not be sufficient in an age of radical uncertainty, as unknown risks demand an extra layer of assessment and planning in which business leaders consider hypotheticals without historical precedents. When faced with this type of uncertainty, a natural response is to do nothing. Yet inaction is, paradoxically, a sort of action, and, in the current environment, inaction is the risk-maximizing choice, while investing time and resources into risk assessment, planning and flexibility is a hazard-mitigating decision.

Of course, firms must answer to their stakeholders, and the costs of resilience measures – of planning for risks, known and unknown – are constantly in tension with financial performance. In public markets, the rise of short-term thinking and quarterly reporting’s tedious demands have tipped the scales toward maximizing near-term financial gains at the expense of long-term investment. It is entirely understandable why business heads would prefer to operate in this manner, as it would be a difficult discussion for a company executive to have with the company’s board if a sizable investment were paid toward mitigating a risk that never materialized. And yet, this sort of resilience-building investment is necessary to minimize existential peril. Oftentimes the best-case scenario is business as usual.

Radical Uncertainty Demands Action From Businesses, Political Leaders and Global Institutions

At the firm level, radical uncertainty demands fundamental and intentional changes in how business leaders think, plan and invest. The orderly world that we in the West have grown accustomed to is getting messier, and company heads cannot afford to be dismissive of the changes they observe or the hypothetical hazards that remain unseen. These leaders must ask, institutionally, what do we know and what do we not know? How much flexibility does our firm need to withstand the next global shock? How can we self-insure and reduce our reliance on increasingly capricious partners? The answers to these questions should then guide business planning and investment to build resilience to extreme risk and uncertainty.

A Framework for Business Risk Assessment in Times of Radical Uncertainty 2

| 1. Identify and Categorize Risks and Opportunities |

|

| 2. Assess Impact and Likelihood |

|

| 3. Develop Mitigation and Contingency Plans |

|

| 4. Enhance Flexibility and Resilience |

|

| 5. Continuous Monitoring and Adaptation |

|

From a global perspective, leaders of the political and institutional order need to champion globalized trade as well as the unrestricted movement of people, money and ideas – the policies and paradigms that constitute the engine of economic growth. Central to this advocacy, political, civic and business leaders must acknowledge those left behind in globalization’s wake while renewing efforts to open doors and widen avenues for poor and underserved communities to access the spoils of a globally connected world. Through these efforts, governments and businesses can restore public faith in the institutions and ideas that have built a global middle class and are foundational to modernity.

In 2022, the Kenan Institute’s Stakeholder Capitalism Grand Challenge found that companies were forced to focus on stakeholder concerns because of the failure of policymakers to address these issues – a demonstration that global risk is not something that businesses can tackle alone. As much as smart governance, ethical actors and organizational strength are needed to diminish risk and uncertainty, a broad-based belief in global institutions and their ability to equitably improve human welfare is essential for constraining power and promoting peace and prosperity.

This article is part of our Grand Challenge series on business resilience.

1 Figure illustrates survey responses to the query: “Which of the following best characterizes your outlook for the world over the following time periods?”

2 Note: This framework’s numbered steps are meant to be an iterative sequence, with the suggested actions undertaken in overlapping and repeated progression.

- Keyword(s):

- business resilience 48

- risk management 54

Building Business Resilience in an Age of Radical Uncertainty