Enhancing the Resilience of Venture Capital

One area of consensus among academic economists and policymakers is the need for greater innovation, an outlook rooted in concern over the lagging rate of productivity growth in many Western nations. In the U.S., for instance, the productivity growth rate has reverted in the last decade to the anemic levels seen from the late 1970s to the mid-1990s after a short surge in the late 1990s and early 2000s. This is a worrisome trend given the strong connections between innovation, productivity and economic prosperity.

Several indications suggest that leveraging innovation to reignite productivity growth in the coming years will be challenging. Research efficiency is falling sharply across fields (Bloom et al., 2020): It appears that ideas are getting harder to find. Large American firms are investing less in R&D, with the decline concentrated in research (as opposed to development) expenditures (Arora, Belenzon, and Sheer, 2021). The origins of these changes is not a settled debate. Is it a response to the unwillingness of the stock market to reward these activities, as those authors suggest, or to shifting corporate incentive schemes (Lerner and Wulf, 2007)? Whatever the causes, the consequences will likely be substantial, as basic research has long been viewed as critical to economic vitality (Griliches, 1986).

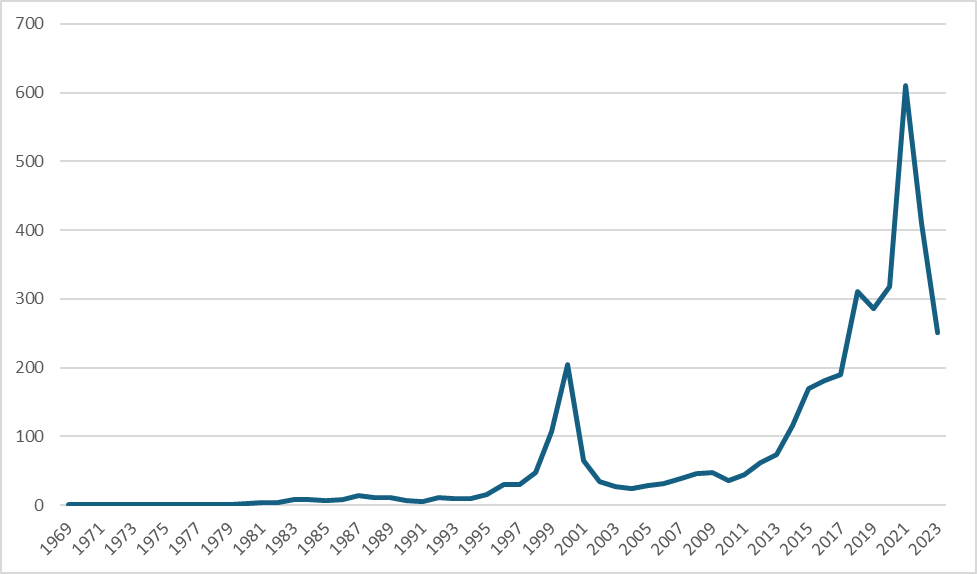

Against this sober backdrop, the venture capital industry appears to be a bright spot in the global innovation landscape. The amount of capital deployed by VC investors and the number of startups receiving funding has grown substantially over the last decade (see Exhibit 1 for data on activity). Entirely new financial intermediaries such as accelerators, crowd funding platforms and “super angels” have emerged at the early stage of new venture finance, competing with traditional early-stage funds. Meanwhile, mutual funds, hedge funds and sovereign wealth funds have deployed large sums of capital into more mature, but still private, venture capital backed firms.

Exhibit 1: Evolution of the Global Venture Capital Industry Between 1985 and 2023

Notes: This exhibit shows total global venture investment, compiled from PitchBook and Refinitiv data, expressed in billions of 2011 dollars. This is an updated version of a graph in Lerner et al. (2024).

Despite VC’s meteoric growth over the past four decades, the pool of capital under management by U.S. VCs remains small in comparison to the several trillion dollars managed by the broader U.S. private equity asset class, which includes buyout and distressed debt funds. Nevertheless, VC is associated with some of the most high-growth and influential firms in the economy. Making up less than 0.5% of firms that are born each year (Puri and Zarutskie, 2012), VC-backed companies represent a very significant share of innovative companies that graduate to the public marketplace.

To view VC’s outsized role, one can examine the impact of venture investing on public firms (Gornall and Strebulaev, 2021). Looking at the subset of firms that were founded after 1968, went public after 1978, and remain traded today (consistent information on venture-backed firms that were acquired or went out of business is hard to find), these firms exhibit an unmistakable effect on the U.S. economy. In mid-2021, these “newer” venture-backed firms made up one-half of the total number of newer public firms and 77% by value at the end of 2020. Yet venture investment’s impact on innovation is truly extraordinary. VC-backed firms make up 92% of all R&D spending in 2020, and 93% of all value-weighted patents in 2018.

This success is no accident, as the academic literature has shown. Much work has focused on the tools employed by venture capitalists to monitor and govern, including the use of staged financing (Gompers, 1995; Neher, 1999), securities that have state-contingent cash flow and control rights (Hellmann, 1998; Cornelli and Yosha, 2003; Kaplan and Strömberg, 2003; 2004), and the active role on VC investors on boards of these firms (Hellmann and Puri, 2000; 2002; Lerner, 1995).

The growth of the venture capital market in the past decade, however, should not blind one to its limitations as an engine of innovation. I would argue that if the reader anticipates that the growth of venture capital will address the challenge of lagging innovation delineated in the introductory paragraphs, these hopes are excessively rosy.

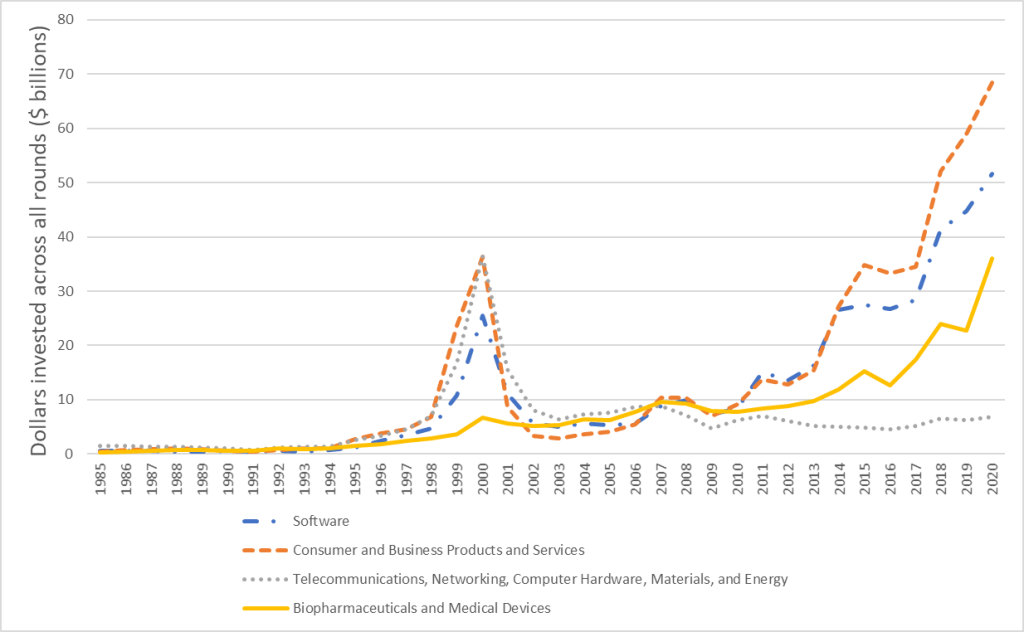

Not enough academic work has focused on the venture capital model’s inherent limitations, many of which may have been exacerbated by VC’s recent growth. I lay out below three distinct areas of concern about venture capital and its ability to successfully spur innovations. These include the very narrow band of technological innovations that fit the requirements of institutional VC investors (see Figure 2 for an industry breakdown) and the relatively small number of VC investors who hold and shape the direction of a substantial fraction of the capital deployed into financing radical technological change.

Exhibit 2: Venture Capital Investment (in Billions of Dollars) into U.S. Startups Between 1985 and 2020, by Sector

Notes: This exhibit reports investment by VC investors into U.S. startups between 1985 and 2020, broken down by four distinct sectors. Data are drawn from the U.S. National Venture Capital Association’s yearbooks and related resources. Consumer and Business Products and Services refer to startups in the following categories: Business Products and Services, Consumer Products and Services, Financial Services, Healthcare Services, IT Services, Media and Entertainment and Retailing/ Distribution. Telecommunications, Networking, Computer Hardware, and Energy refers to startups in the following categories: Computers and Peripherals, Electronics / Instrumentation, Networking and Equipment, Semiconductors, Telecommunications, Industrial/ Energy and Other. Biopharmaceuticals and Medical Devices refers to startups in the following categories: Biopharmaceuticals and Medical Devices and Equipment.

A third concern relates to the cyclicality of governance. Venture capital has traditionally been a tough business, characterized by onerous stock purchase agreements (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2003). Moreover, Kaplan, Sensoy and Strömberg (2009) and Ewens and Marx (2018) document, these are not just “paper rights” – frequent turnover of management has been the rule. These patterns have changed dramatically in the past decade. Across the board, “founder friendly” terms appear to have replaced the onerous provisions traditionally demanded by venture capitalists. Several potential explanations can be offered for this shift.

First is an increase in competition between venture capitalists associated with the industry’s recent growth. Given the very skewed nature of venture returns – a few deals generate the bulk of the returns (Hall and Woodward, 2010; Ouyang, Yu, and Jagannathan, 2020) – the competition to get access to the firms that show potential to generate outsized returns is particularly intense. Responding to the heightened competition, VC groups appear to be vying to outdo each other in the hospitable terms offered to company founders.

To an economist, however, this explanation is puzzling. If the intensive governance provided by venture capitalists is socially beneficial – as generations of academic analyses suggest – why would VC groups choose to abandon it? Should venture firms not compete exclusively by offering entrepreneurs progressively higher valuations (and less dilution of their initial equity stakes) and not abandon governance provisions? More research is needed to fully understand these dynamics, yet one possible explanatory factor is that entrepreneurs now have a lot of discretion in who funds their startups, and so they strategically choose more hands-off funders (Hsu, 2004), perhaps underestimating the need for VC governance.

In this final section, I summarize elements that would require the VC industry to reconceptualize and internalize to become more effective and increase sector resiliency. These hypotheses, which are designed to provide some ideas to practitioners and academics interested in thinking “outside the box,” are developed in greater detail in Lerner and Nanda (2020) and, regarding the organizational and incentive structure of venture partnerships, in Lerner (2012). My first set of suggestions relate to the design of the venture fund. Since the early days, VC funds have been eight to 10 years in scope, with provisions for one or more one-to-two-year extensions. Venture capitalists typically have five years in which to invest the capital, and then are expected to use the remaining period to harvest their investments.

The uniformity of these rules is perplexing, given that funds differ tremendously in their investment foci, from quick-hit social media businesses to long-gestating biotechnology projects. In periods when public markets are enthusiastic, venture capitalists may be able to exit still-immature firms that have yet to show profits or even, in some cases, revenue. Given the short fund lifecycle – and the fact that VC groups shift their focus after a few years to raising their next fund – it is not surprising that venture funds have increasingly focused on sectors characterized by fast innovation “clock speeds,” such as software and social networking. Revisiting the uniformity of VC fund life is an important first step.

A second idea relates to de-risking ventures. Venture funds invest in stages, enabling them to reinvest in businesses that continue to show promise while abandoning those that do not (Reis, 2011). One reason for the dramatic rise in venture capital directed toward software and related enterprises is that this industry has exhibited rapid declines in the cost of learning about a venture’s ultimate viability. The VC model is less suited for industries with substantial regulatory and technological risk, such as clean energy and advanced materials.

A solution for de-risking ventures begins with the process that VCs use to identify promising new ideas. The traditional approach entails entrepreneurs coming to VCs to pitch them new ideas and VCs deciding whether to fund them. This process allows investors to maintain an arm’s-length relationship from the entrepreneurial team, reducing the entrenchment that is sometimes associated with corporate R&D and internal capital markets. Some VC investors specializing in biopharmaceuticals, such as Third Rock Ventures and Flagship Pioneering, have begun to use an alternative approach: to incubate and finance ideas in-house. This process reduces asymmetric information because much of the entrepreneurship team comes from within the fund, while enabling the VC firm to fund what it believes is the most promising idea as opposed to selecting among the ideas that walk through the door. Such new approaches may hold promise for widening the scope of venture capital investment.

Josh Lerner is a 2024 Kenan Institute Distinguished Fellow and the Jacob H. Schiff Professor at Harvard Business School, specializing in venture capital, private equity and innovation management, as well as a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. His contributions to the institute’s Grand Challenge focusing on business resilience provide key insights and research that help examine and drive solutions to the most complex and timely issues facing business and the economy today.

Acknowledgments

Harvard Business School’s Division of Research provided funding for this work. This essay is based on Lerner (2012) and especially Lerner and Nanda (2020). It draws on the ideas in Gompers and Lerner (2001a), Kerr, Nanda and Rhodes-Kropf (2014), and Ivashina and Lerner (2019). I owe a debt of gratitude to Paul Gompers, Bill Janeway, Steve Kaplan, Victoria Ivashina, Ramana Nanda, Matthew Rhodes-Kropf, William Sahlman, and especially Felda Hardymon for many helpful conversations over the years. I have received compensation from advising institutional investors in venture capital funds, venture capital groups, and governments designing policies relevant to venture capital. All errors and omissions are my own.