Meeting the Future Demand for Primary Care Services

The primary care market in the United States has seen major shifts in recent years. Retail companies have expanded their footprint in the sector; for example, Amazon’s acquisition of One Medical means that the e-commerce giant owns and operates more than 220 primary care offices, offering a suite of virtual and preventative care services. CVS also further entered the primary care arena by purchasing Oak Street Health, a primary care services provider operating 169 offices across 21 states. Other recent examples include Walgreens’ acquisition of Summit Health, as well as the planned 2023 expansion of Walmart Health, the primary care services unit within select Walmart Supercenters. In addition to retail and private equity expansion into primary care, traditional health systems have continued to consolidate via mergers and acquisitions, causing instability in the landscape as physician groups adjust to new ownership. Physician employment continues to trend from self-employed (physicians owning and working out of their own practices) to employed under a health system, contract agency or, more recently, retail companies. Retail entrance to this sector of healthcare is likely to continue the trend of self-employed physician rates decreasing over time.1

Given such sweeping changes in primary care services and providers, questions remain about what effect these events might have on the primary care workforce. Will current medical students now aspire to work as primary care providers under the Amazon or Walgreens umbrella? Will the high burnout rates cause current physicians to leave traditional primary care and seek new opportunities in private equity-backed preventative care ventures? This insight seeks to examine what primary care now encompasses, how primary care physicians in this field are faring, trends within medical residencies, and whether demand for primary care services will ultimately be met.

What Is Primary Care Today – and Who Offers It?

As large numbers of new commercial entities enter the field, it’s easy for the original definition of primary care to get a bit murky. The influx of new terminology via marketing, rhetoric and service definitions can obscure what primary care is – and who might be offering these services.

This ambiguity existed long before the changes outlined above. Even the National Academy of Medicine has reconsidered the definition of primary care for decades. One of its current definitions is likely the best encapsulation of this new, nuanced era of primary care:

“Primary care is the provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community.”

Table 1, Showing Physicians Who Provide Primary Care 4

| General – Internal Medicine |

| Family Medicine |

| General – Pediatrics |

| Medicine – Pediatrics |

| Geriatrics |

Physicians, physician assistants and nurse practitioners are the most common providers of the umbrella of services now under primary care. In 2010, about 210,000 physicians, 56,000 nurse practitioners and 30,000 physician assistants were practicing primary care in the United States. Services are still typically administered through traditional medical offices, with more than 1 billion physician office visits a year in the United States. About half of them were made to primary care physicians.3 However, recent retail entrants into the field hope to change this model. Amazon CEO Andy Jassy has stated, “If you fast-forward 10 years from now, people are not going to believe how primary care was administered.” The traditional direct primary care means of service delivery is unlikely to fade away quickly, but new entrants marketing concierge care are vigorously pushing for change. As of today, One Medical’s subscription model gives subscribers access to 24/7 asynchronous virtual care (although subsequent visit costs still route through an individual’s insurance plan). Virtual visits and concierge care are not entirely new, and subsequent orders and tests will still need to be done at physical locations. However, the immediate access to providers and referral services being marketed by traditionally nonmedical corporations seems likely to change the pace and rate of change to current service models across the industry – especially as competition increases among these new entrants.

While retail’s entrance into the primary care space could mean more access for patients, it is likely to bring cumbersome process and workflow changes to those delivering the care. Often these entities have their own proprietary electronic health record systems, which new providers will have to learn to navigate. Additionally, these systems often have limited interoperability with existing standard health systems (Epic, Cerner, etc.). These incompatibilities increase barriers to continuity of care and further exacerbate healthcare data silos. Physicians may also have to accommodate more volume and throughput, which has two possible shortcomings. Not only could this shorten allocated times per patient visit, but it might potentially worsen burnout in a physician specialty that is experiencing record levels of professional dissatisfaction.

Primary Care and Internal Medicine Physician Concerns, and Potential Movement Across the Market

It is clear that physician burnout and workplace dissatisfaction are major factors behind the changing nature of primary care. One 2016 study from the Journal of General Internal Medicine reported that of 1,235 clinicians, 67% experienced high stress, with low work control, insufficient support staff, documentation time pressure, devalued medical education and low-value alignment with leaders contributing to burnout.4 A cross-sectional analysis of family medicine resident physicians highlighted that depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, issues on personal achievement, and resilience were outcome variables that needed to be addressed to increase physician wellness and update workplace policies.5 In his 2019 report for the American Journal of Medicine, Dr. Scott Yates states that physicians struggle to come to terms with burnout or even recognize their symptoms and seek help.6 Overall, it is estimated that $4.6 billion in administrative costs impacting clinical care hours is attributed to physician burnout in the U.S.7

This issue can be examined under the lens of pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic conditions to illuminate any potential exacerbating factors. Indeed, the pandemic accelerated burnout among clinicians, with an increased prevalence of psychological and moral distress, anxiety, depression and suicide.8 In the first year of the pandemic alone, the United States observed 3,607 healthcare workers and 291 physician deaths in the United States.9 While physician burnout has been discussed in the healthcare worker communities since 1974, COVID-19 has grossly amplified the burden on clinicians, causing increased clinical responsibilities, overwhelming patient load, personal protective equipment issues and other hospital-grade facility shortages, duty hour changes, prolonged electronic healthcare records documentation hindering workflow, and barriers for coordinated care. In light of these factors, even the stoic undertones that dictate medical workplace culture have begun to give, resulting in an exodus of clinicians from clinical medicine after the pandemic.

Are Internal Medicine Physicians Seeking Different Environments?

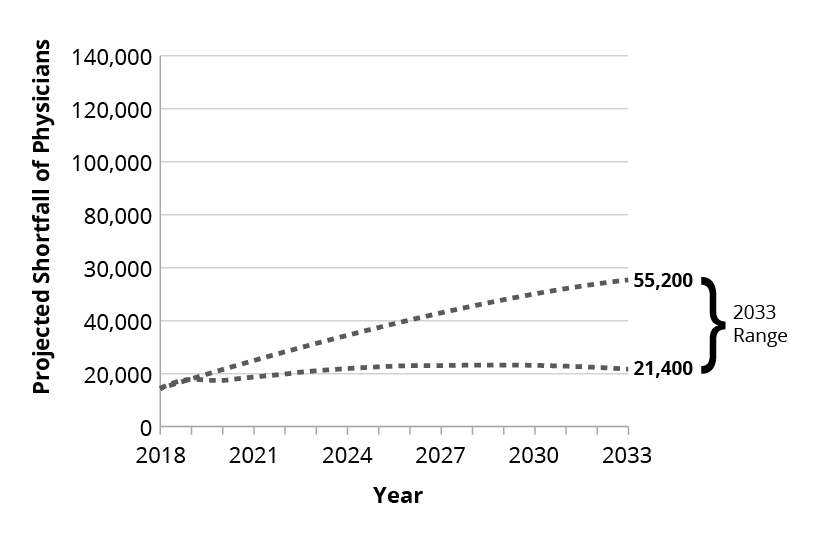

Indeed, since the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, a survey published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovation, Quality & Outcomes reported that 1 in 3 physicians intend to reduce their work hours and, more worryingly, 1 in 5 physicians intend to leave their practice within two years because of direct burnout effects from the pandemic.10 This was substantiated when a report from Definitive Healthcare revealed that between Q1 2020 and Q4 2021, 117,000 physicians left their profession.11 Internal medicine and family practice physicians were among the specialties with the highest rates of turnover during this period. Extrapolating into the future, the projected shortage of primary care physicians is expected to reach between 21,400 and 55,200 by 2033, according to a report by the Association of American Medical Colleges.12 Due to these issues in the primary care clinical sector, possible career alternative opportunities that former physicians may consider are healthcare consulting, digital/telehealth innovations, corporate physician jobs and medical director positions at healthcare organizations, to name a few. Consequently, roles in these related fields are becoming more enticing to physicians as burnout continues to grow.

Figure 1: Projected Primary Care Physician Shortfall Range, 2018-2033

Residency Trends: Pipeline for New Primary Care Physicians

As the coming physician shortage becomes a growing concern, we must examine the pipeline for new primary care physicians applying for U.S. residency training. The National Resident Matching Program revealed that the number of complete three-year (categorical) internal medicine residency positions has jumped from 7,542 places in 2018 to 9,380 places in 2022 – an increase of 24% over the last five years.13 Similarly, the number of complete three-year (categorical) family medicine positions has increased 35% over the last five years from 3,629 places in 2018 to 4,916 places in 2022. While these two programs (categorical internal medicine and categorical family medicine) are not exclusive, they provide the vast majority of residents that will eventually become primary care physicians. Other residency programs such as medicine-pediatrics and general pediatrics also echo growth in positions over the last five years. Despite this growth, however, the key will be the retention of these residents from their training and board certifications, as well as a smooth, sustainable transition into long-term practice in primary care.

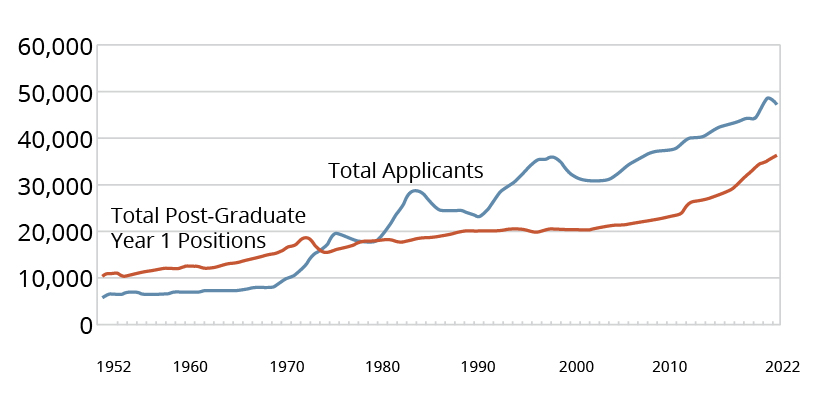

Looking at the bigger picture of the medical workforce in the United States, we should bring into discussion the total number of applicants in U.S. residency training (internal medicine, family medicine as well as others such as surgery, radiology, anesthesiology, etc.). In 2022, 42,549 applicants applied to residency training, with 34,075 successfully matching into a first-year residency program. This meant that 8,474 hopeful medical students and physicians from the United States and around the world were rejected.14 While there are many reasons for an unsuccessful applicant, such as lack of U.S. clinical experiences, inadequate letters of recommendation or research, and low board scores, it is clear that demand has continued to supersede the supply since the 1970s as the resident applicant-per-position ratio has steadily continued to grow.

Figure 2: Applicants and 1st Year Positions in the Match, 1952-2022

According to the Congressional Research Service report of 2022, residency programs and graduate medical education are funded predominantly through Medicare via the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, with $16.2 billion paid by Medicare in the financial year of 2020.15 In light of the projected shortages of primary care physicians, this gives reason for increased funding to residency programs. Specifically, the establishment of new programs across the United States and an increase in the number of positions in existing programs (particularly in internal medicine and family medicine programs) may offer a potential solution.

Meeting Future Primary Care Demands

Will this flurry of activity in the primary care space by for-profit organizations affect demand? While it’s still early, the consensus is that demand for services will continue to increase but that the supply of primary care physicians and providers will not keep pace. A recent brief by Bain & Co. estimated that by 2030, “nontraditional primary care providers” will make up a third of the primary care market. These companies will likely alleviate barriers to access through virtual care and other innovations, which will require more workers to meet the demand for services.16 Before this flurry of activity in the market, demand for primary care services was already estimated to increase 1.4% annually until 2029.17 Meanwhile, the supply of family physicians is expected to increase only 6% by 2030, but demand is projected to increase 13%.18

This mismatch of supply and demand is present for each physician group practicing within primary care. The greatest difference in supply and demand is noted among geriatric care physicians (8% decrease in supply, 50% increase in demand). An additional issue is the geographic dispersion of this clinical workforce. As seen in Figure 3, even if primary care physicians can somehow match demand over the next decade, many physician concentrations are dispersed across the U.S., with southern and eastern states seeing lower numbers of physician entrants to primary care. Innovations coming from new retail companies leveraging virtual care could mitigate some of these geographic concerns – especially among rural populations – but access to subsequent tests and orders by virtual care visits that require physical locations may become confounders to a seamless primary care interaction.

Figure 3: Percentage of Physicians Entering Primary Care by State in 2020

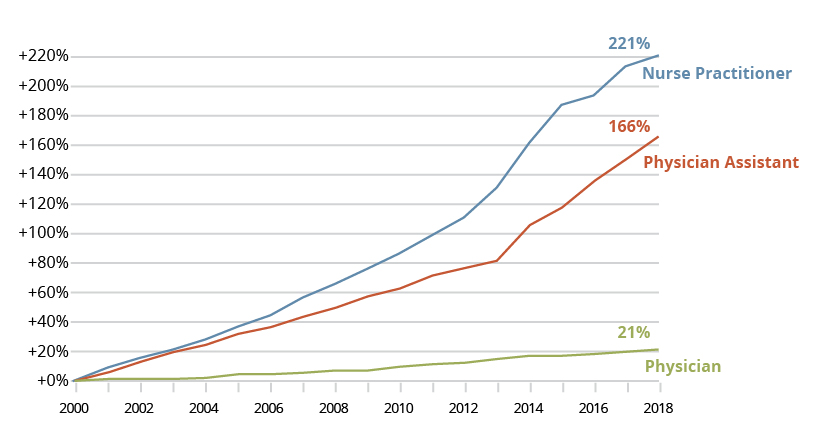

The two other major workforces providing primary care services, nurse practitioners and physician assistants, are projected to outpace the supply of primary care physicians. Figure 4 shows the stark differences in the cumulative growth of nurse practitioners, physician assistants and physicians in North Carolina over the past 20 years.

Figure 4: Cumulative Percentage Growth per 10,000 Population since 2000 for Nurse Practitioners, Physicians, Physician Assistants in North Carolina

These two occupations will be key workforces as the healthcare industry seeks to meet the demand for services. Scope of practice and other policy constraints exist across the U.S. that limit how these workforces now provide primary care services. Usually, a physician is still required to oversee aspects of care delivered by these occupations. However, as physician supply lags behind these two other professions, there will likely be strong emphasis and pressure from multiple industries to adjust the scope of practice laws, and political policy intervention is likely to be required to address the discrepancy.

As we noted above, residency trends gravitating toward primary care, while positive, are not going to alleviate the issue of the primary care physician shortfall. More concerning is the roughly 100,000 physicians who left the workforce during the pandemic; many of the physicians who quit were capable of providing primary care. With potential policies and statewide practice laws changing in the future, perhaps a critical avenue for these burnt-out primary care physicians would be to take leadership positions and guide providers in healthcare retail companies such as One Medical and Oak Street Health, ensuring quality of care is regulated to appropriate standards implemented from authorities such as the American Medical Association and American College of Physicians.

Conclusion

A lot of attention is being given to primary care. We highlighted how large corporations have entered the market. This could spawn necessary innovation in how primary care services are rendered and improve patient access to care. However, the primary care workforce still needs major profession fixes and attention. Primary care providers are demonstrating record levels of burnout and massive turnover rates. Attrition from the primary care field will likely continue – and while resident trends are positive, it may not be enough to improve the supply of providers to meet the demands stoked by industry. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are showing major workforce growth, which is ideal to meet demand, but medical policy and scope-of-practice issues are likely to follow these professions, potentially limiting their ability to mitigating the primary care shortfall.

Overall, attention will continue to fixate on primary care given these new market shifts. Audiences will be eager to see if Amazon, CVS and others will be successful in their new endeavors. We can hope the attention is equally focused on expanding the primary care workforce and, more importantly, ensuring the quality of care is regulated with adequately licensed healthcare providers (physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants). These workers are truly the essential element in primary care, as no primary services would be rendered without them. With that in mind, robust protections should be implemented to ensure that interest in this field from large companies does not harm the providers.

1 American Medical Association. (2019, May 6). Employed physicians outnumber self-employed [Press Release]. https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/employed-physicians-outnumber-self-employed

2 Deutchman, M., Macaluso, F., Chao, J., Duffrin, C., Hanna, K., Avery, D. M., Onello, E., Quinn, K., Griswold, M. T., Alavi, M., Boulger, J., Bright, P., Schneider, B., Porter, J., Luke, S., Durham, J., Hasnain, M., & James, K. A. (2020). Contributions of US medical schools to primary care (2003-2014): Determining and predicting who really goes into primary care. Family Medicine, 52(7), 483-490. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2020.785068

3 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). FastStats: Ambulatory Care Use and Physician office visits. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/physician-visits.htm

4 Linzer, M., Poplau, S., Babbott, S., Collins, T., Guzman-Corrales, L., Menk, J., Murphy, M. L., & Ovington, K. (2016). Worklife and wellness in academic general internal medicine: Results from a national survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(9), 1004-1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3720-4

5 Buck, K., Williamson, M., Ogbeide, S., & Norberg, B. (2019). Family physician burnout and resilience: A cross-sectional analysis. Family Medicine, 51(8), 657-663. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2019.424025

6 Yates, S. W. (2020). Physician stress and burnout. The American Journal of Medicine, 133(2), 160-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.08.034

7 Han, S., Shanafelt, T. D., Sinsky, C. A., Awad, K. M., Dyrbye, L. N., Fiscus, L. C., Trockel, M., & Goh, J. (2019). Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine, 170(11), 784-790. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-1422

8 Dzau, V. J., Kirch, D., & Nasca, T. (2020). Preventing a parallel pandemic — A national strategy to protect clinicians’ well-being. The New England Journal of Medicine, 383(6), 513-515. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2011027

9 The Guardian. (2020, August 11). Lost on the frontline: Covid-19 healthcare workers deaths in the US. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2020/aug/11/lost-on-the-frontline-covid-19-coronavirus-us-healthcare-workers-deaths-database

10 Sinsky, C. A., Brown, R. L., Stillman, M. J., & Linzer, M. (2021). COVID-related stress and work intentions in a sample of US health care workers. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Innovations, Quality & Outcomes, 5(6), 1165-1173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2021.08.007

11 Definitive Healthcare. (2019). Addressing the healthcare staffing shortage. https://www.definitivehc.com/sites/default/files/resources/pdfs/Addressing-the-healthcare-staffing-shortage.pdf

12 Association of American Medical Colleges. (2020). The complexities of physician supply and demand: Projections from 2018 to 2033. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-06/stratcomm-aamc-physician-workforce-projections-june-2020.pdf

13 National Resident Matching Program. (2022). Results of the 2022 NRMP Main Residency Match. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data_Final.pdf

14 National Resident Matching Program (2022)

15 Congressional Research Service. (2022). Graduate medical education (GME) in Medicare. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10960

16 Ney, E., Berger, E., & Fry, S. (2012). Primary care 2030. Bain & Company. https://www.bain.com/insights/primary-care-2030/