Navigating Marketplace Threats: An Analysis of Resilience Strategies from The CMO Survey

The modern business landscape is characterized by unprecedented volatility and uncertainty. Companies face numerous threats – from increased competition and regulatory changes to shifts in customer behaviors and disruptions in go-to-market strategies due to rapid technological change and unforeseen global pandemics. There is now a sizable academic literature on the nature of resilience and its effects on firm survival. Despite this, we lack a view of marketplace threats and resilience strategies from the perspective of actual managers. I leverage data from The CMO Survey, a study of marketing leaders, to uncover this perspective. I perform simple descriptive analysis on these data and show that what leaders emphasize is not always what correlates with effective coping.

The mission of The CMO Survey is to collect and disseminate the opinions of marketing leaders to predict the future of markets, track marketing excellence and improve the value of marketing in organizations and society (see https://cmosurvey.org/). Since its beginning in 2008, The CMO Survey is the longest-standing comprehensive survey of marketing spending and performance. Results from the 33rd edition, which I discuss in this article, are based on a sample of 260 marketing leaders at for-profit US companies, 97% of whom hold positions at VP level or higher.

I set the stage for this descriptive approach by approaching resilience in the broadest terms possible – as the organization’s ability to cope and manage effectively or recover when facing threatening or challenging circumstances (Sutcliffe and Vogus 2003)1. This does not say how or why this coping or recovery occurs. It does not specify the processes or resources that are used nor does it indicate if this ability is a planned or improvised solution and whether these actions build on or deviate from organizational knowledge and skills. These points – which are quite varied even in the literature – will be addressed in the survey results. The view adopted in this article does, however, stipulate that the response is at the organizational level. This is not to say that actions may not have been initiated by individual leaders and/or carried out by teams or functions. However, the response is ultimately at the firm or organizational level.

The Nature of Marketplace Threats and Coping Success

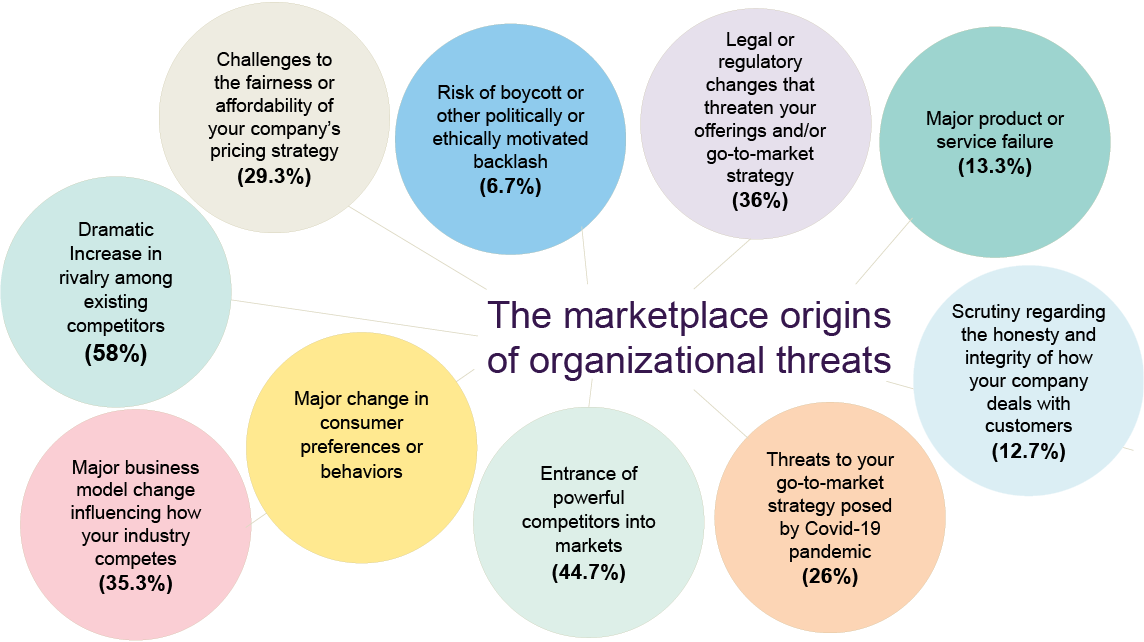

I begin by examining the different types of challenges that might emerge for organizations as they interact with the marketplace. This novel account, shown in Figure 1, reveals that the most common threats faced by companies in the last decade include a dramatic increase in rivalry among existing competitors in their industry (58% of companies), the entrance of powerful new competitors into existing markets (44.7% of companies), major changes in consumer preferences or behaviors upon which their business is based (44% of companies), and legal or regulatory changes that threaten their offerings and/or go-to market strategy (36% of companies). These threats were also judged to be among the most difficult faced by companies.

Companies reported a moderate ability to cope effectively with these challenges, averaging a score of 4.8 out of 7, where 1 = “very poorly” and 7 = “very well.” Despite this perception, significant negative consequences were also associated with these challenges, including lost revenue (76.3% of companies), decreased profits (56.8%), and damaged relationships with employees, customers and partners to a lesser degree (see Figure 2).

Interestingly, marketing leaders reported significantly higher coping ability when facing “internal” challenges (e.g., major product or service failure), “political” challenges (e.g., legal and regulatory challenges), and “non-market” challenges (e.g., go-to-market challenges due to COVID-19) relative to core “market” challenges associated with competitor rivalry and entry or changes in consumer preferences or behaviors.

The Role of Coping Mindset, Processes and Resources in Resilience

Across the literature, research has examined the types of mindsets people in the company have about the challenges they face with the view that these coping2 mindsets impact behavior and outcomes in important ways. Likewise, the organizational processes and resources used during the coping process can have consequential impacts. Leader reports about the use of these three phenomena are now examined, followed by how they actually influence coping effectiveness.

Coping mindset2. Leaders reported a more optimistic (78.2% of companies), proactive (57.6% of companies), flexible (85.2% of companies), and slightly more fearful (53.5% of companies) coping mindset among people in the company as they worked through these marketplace challenges. This is versus a pessimistic (21.8%), defensive (42.2%), inflexible (14.8%), and fearless (46.5%) outlook. Examining how well these mindsets predict effective coping, results show that more optimistic, proactive and flexible mindsets all enhance coping effectiveness. A more fearless mindset is also more productive for coping, challenging the tendency among leaders to be more fearful in their thinking.

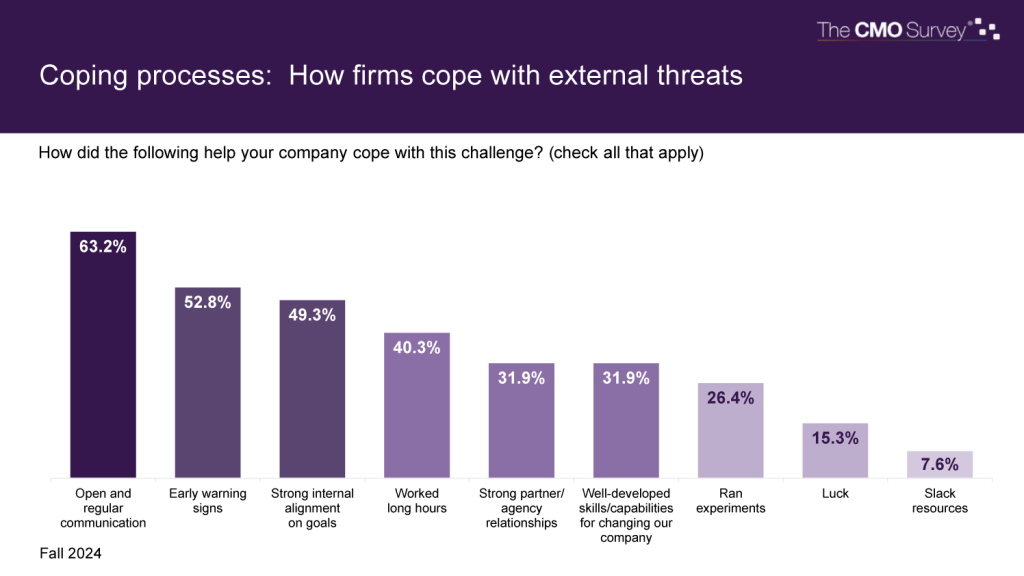

Coping processes. The survey also asked leaders about the various coping processes they used when facing these marketplace challenges. Figure 3 shows the frequency of these activities with “open and regular communication” at the top of the list (63.2% of companies), followed by “early warning signs about the challenge” (52.8% of companies), and “strong internal alignment on goals” (49.3% of companies). All of these top-three processes are also highly predictive of effective coping.

However, there was a surprise. The most predictive of all coping processes was “well developed skills/capabilities for changing our company” – an approach used by only about one-third of all companies (see Figure 3). This means that this key process is currently being underused relative to its importance to effective coping.

Finally, “ran experiments” and “worked long hours” did not predict effective coping, while “luck” and “availability of slack resources” were negatively correlated with successful coping. This negative effect of slack resources follows other research finding that high levels of slack resources can buffer the pain of a challenge and foster complacency, increasing risk aversion (Tan and Peng 2003)3. When threats require change, these tendencies can challenge survival.

Coping resources. When asked to rate the coping resources most important to their company’s ability to cope effectively with the challenge, “financial resources” is rated most important (average rank of 1.8, where 1 = most important, see Figure 4). A close second is “human resources” (average rank 1.9), followed by “customer relationships” (2.0), “brand reputation” (2.0), “partner relationships” (2.2), and “outside help” (2.3).

Considering the impact of these resources on coping effectiveness across all types of threats studied, results contradict the importance leaders place on these resources. First, the resource that is most highly correlated with effective coping is “outside help,” despite it being viewed as least important by leaders. Second, “financial resources” is not related to effective coping, despite being rated as most important, pointing to another mismatch between what leaders rate as most important and what is most predictive of coping effectiveness.

When we look at the specific threats studied in Figure 1, we find a more nuanced view that appears to reflect the idea of “fit” between the coping resource and nature of the threat the firm is facing. For example, for “internal threats,” such as a major product or service failure, human resources are most important to coping effectively. However, for “political threats,” such as legal or regulatory challenges, and for “customer threats,” such as a major change in consumer preferences or behaviors upon which your business is based, customer relationships are the most important resource. Finally, brand reputation resources are most important when facing the threat of increased competitive rivalry. These results suggest that leaders consider how resources may be differentially important when working to resolve different types of challenges.

Resilience Strategies: Prevalence and Impact

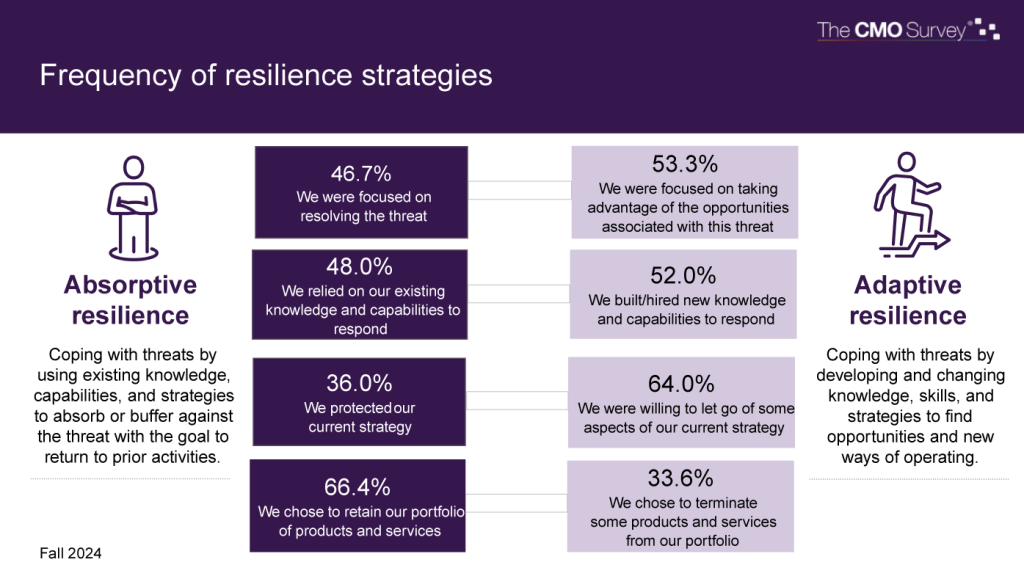

Leaders were asked to rate their use of two different types of resilience strategies (Conz and Magnani 2020)4. Absorptive resilience reflects a focus on coping with threats by using existing knowledge, capabilities and strategies to absorb or buffer the threat with the goal to return to prior activities. Key actions focus on resolving the threat, leveraging existing knowledge and capabilities, protecting current strategies, and maintaining existing product and service portfolios.

Looking beyond restoration, adaptive resilience reflects a focus on coping with threats by developing and changing knowledge, skills and strategies to find opportunities and new ways of operating. Key actions focus on taking advantage of opportunities associated with the threat, developing new capabilities, reconfiguring strategy and eliminating aspects of the firm’s portfolio of products and services.

Examining the frequency of these strategies, leaders rated three of the four adaptive resilience strategies at higher levels than the absorptive resilience strategies, as shown in Figure 5. The only exception is that leaders were more likely to retain their portfolios of products and services (66.4%) than to terminate some products and services from their portfolios (33.6%).

Considering the consequences of using an adaptive strategy, results indicate that leaders rate their organizations’ level of coping effectiveness higher and that their organizations experienced stronger employee outcomes (fewer layoffs and stronger morale) and stronger customer relationships. On financial outcomes, there is no difference in the profitability of absorptive versus adaptive resilience strategies. However, an adaptive strategy does produce a loss of revenue. This might be expected as the company builds its brand and customer relationships – both of which can take time.

In terms of the types of coping mindsets, processes and resources that tend to be correlated with the use of adaptive strategies, results indicate that mindset is not predictive. In other words, adaptive and absorptive resilience strategies tend to rely on the same mindsets. However, in terms of processes, companies using adaptive resilience strategies are more likely to rely on “well-developed skills/capabilities for changing the company” and “running experiments” compared with absorptive resilience. It makes sense that these processes would rise to the top given the importance of change to adaptive resilience. The other coping processes show no difference between the two resilience strategies. Finally in terms of resources, adaptive resilience strategies tend to rely more on human resources and partner relationships.

What do these results imply about how organizations might plan for different resilience strategies? Given the focus of absorptive resilience strategies on buffering the organization from threats to allow it to survive, it is important to use planning to build resources that prepare the organization to withstand threats. The difficulty is predicting which knowledge, skills and resources may be needed when the exact threat is unknown – making it a challenging and expensive planning problem. On the other hand, adaptive resilience puts the emphasis on change management skills. Hence, leaders do not need to invest in any particular resource. Instead, they should invest in the development of three key organizational skills.

First, organizations need to practice reconfiguring their resources to adapt. These skills are often referred to as dynamic capabilities as they help the organization change as the external environment changes. Teece, Pisano, and Shuen (1997, p. 521)5 notes, “The capacity to reconfigure and transform is itself a learned organizational skill. The more frequently practiced, the earlier accomplished.”

Second, organizations need to build a learning culture that is aware of threats, interprets information accurately and is not resistant to changes in beliefs and behaviors that are necessary for the organization to survive and thrive (e.g., Day 19946, Deshpande, Farley, and Webster 19937; Slater and Narver 2005)8. Weick and Sutcliffe (2007)9 discuss the difficulty of accurately seeing the world around the organization because organizations have blind spots, expectations, habits and a tendency to seek confirmatory evidence. Getting to accurate interpretation requires what Weick and Sutcliffe refer to as mindfulness – “a rich awareness of discriminatory detail, meaning that when people act, they are aware of context, of ways in which details differ, and of deviations from their expectations” (Weick and Sutcliffe 2007, p. 32)9.

An unheralded, but important, aspect of resilience is unlearning. Unlearning is important because new actions may require changes in existing approaches or strategies. If, for example, a new competitor challenges the firm’s go-to-market strategy or leapfrogs its current products, it may be necessary for the firm to find new ways to approach these activities. The willingness to make changes is costly in the short term as the organization retools and re-strategizes its approach. For this reason, many organizations do not change and operate at suboptimal levels. Change is difficult for other reasons, including training, norms and sunk costs. In his work on studying wildland firefighters, Weick (1996)10 recounts what happened at the Mann Gulch and South Canyon fires when firefighters perished because they did not drop their heavy tools and packs while trying to escape. Part of the explanation for this tragedy is that the firefighters had not practiced dropping their gear and that under duress, they relied on training, which told them to keep their valuable tools with them at all times. “Dropping your tools” is Weick’s reminder that surviving threats often requires change (and unlearning).

Third, organizations need to find a way to use a portfolio of planning and improvisational approaches as they develop their new approaches. Results show that leaders report using “planned solutions” when coping with threats approximately 51.9% of the time and “improvisational approaches” 48.1% of the time. Improvisation occurs when organizations do not plan in advance, but instead compose and execute their actions at the same time (Moorman and Miner 199811; Miner, Bassoff, and Moorman 200112). Just like actors or musicians performing outside of a script or score, results suggest that organizational actors make up actions as they go or “on the fly” with a high degree of regularity. Considering the impact of improvisation versus planning on coping effectiveness, results indicate no difference. This finding is consistent with research in this area that suggests that improvisation can be helpful or harmful to organizations depending on the amount of knowledge or experience it has in the area in which is improvising and on the level of real-time information exchange that occurs during the process (Moorman and Miner 1998)11.

Limitations and Conclusions

While The CMO Survey provides valuable data, it is important to consider some limitations. The reliance on self-reported data and the use of cross-sectional analysis might lead to biases. Future research studying these ideas in a longitudinal could yield more valid insights and deep qualitative work might yield deeper insights.

Notwithstanding these weaknesses, the strength of this research is that it studies marketplace threats, whereas a great deal of other resilience research focuses more on internal threats or those emanating from financial markets. Another strength of this research is that offers a rare glimpse into how leaders view their companies’ approaches to managing marketplace threats, including the mindsets, processes, resources and strategies they use. We observe results that are consistent with the literature as well as findings that show what leaders rate as important is not necessarily what is most predictive of effective coping with the marketplace threats.

References

1 Sutcliffe, Kathleen M. and Timothy J. Vogus (2003), “Organizing for Resilience,” in Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline. K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton and R. E. Quinn, eds. San Francisco, CA, Berrett-Koehler, 94-110.

2Note that “coping” was intentionally not defined to reflect a particular approach or strategy of managing through the challenge. Different coping strategies are examined in the survey and discussed later in the article. However, here the focus is on the leader’s subjective sense of how well his or her organization coped with the threat.

3Tan, Justin and Mike W. Peng (2003). “Organizational Slack and Firm Performance During Economic Transitions: Two Studies from an Emerging Economy,” Strategic Management Journal, 24, 1249-1263.

4 Conz, Elisa and Giovanna Magnani (2020), “A Dynamic Perspective on the Resilience of Firms: A Systematic Literature Review and a Framework for Future Research,” European Management Journal, 38 (3), 400-412.

5 Teece, David J., Gary Pisano, and Amy Shuen (1997), “Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management,” Strategic Management Journal, 18 (7), 509-533.

6 Day, George S. (1994), “The Capabilities of Market-Driven Organizations,” Journal of Marketing, 58 (October), 37-52.

7Deshpandé, Rohit, John U. Farley, and Frederick E. Webster, Jr. (1993), “Corporate Culture, Customer Orientation, and Innovativeness in Japanese Firms: A Quadrad Analysis,” Journal of Marketing, 52 (1), 23-36.

8Slater, Stanley F. and John C. Narver (1995), “Market Orientation and the Learning Organization,” Journal of Marketing, 59 (July), 63-74.

9Weick, Karl, E. and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe (2007), Managing the Unexpected. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass.

10 Weick, Karl E. (1996), “Drop Your Tools: An Allegory for Organizational Studies,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 41 (2), 301-313.

11Miner, Anne, Paula Bassoff, and Christine Moorman (2001), “Organizational Improvisation and Learning: A Field Study,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 46 (June), 304-337.

12 Moorman, Christine and Anne S. Miner (1998), “The Convergence of Planning and Execution: Improvisation in New Product Development,” Journal of Marketing, 62 (July), 1-20.