Resilience: Adversity’s Antidote

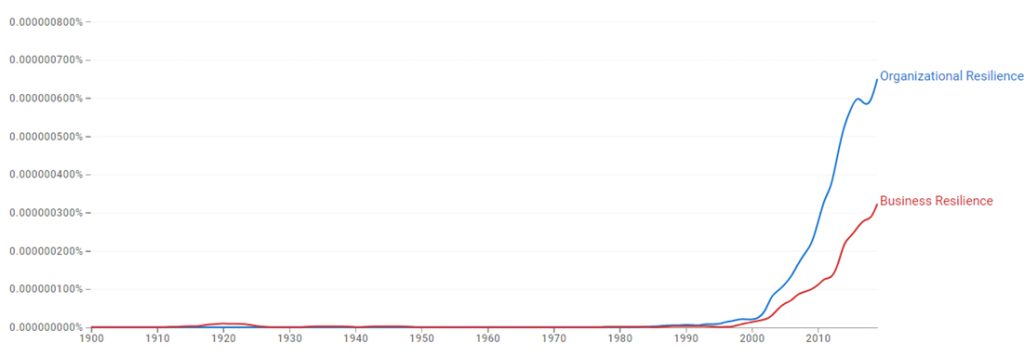

Resilience has become increasingly important not only for individuals but also for organizations. Indeed, interest in organizational/business resilience has surged in the past two decades, as Figure 1 shows.1

Figure 1: Increase of Interest in Resilience

Resilience enables organizations to weather sweeping challenges such as pandemics, workforce disruptions and economic surprises that arise seemingly without warning.2 But it isn’t just sweeping challenges that fuel business needs for resilience. Organizational life is filled with smaller challenges, predictable surprises and everyday uncertainties and risks such as supply chain shortages, unsettling social media trends or information technology malfunctions that can disrupt organizational functioning. Knowing more about resilience and its building blocks can enable emergent flexibility and adaptability. Drawing on two decades of research, we examine some basic elements of resilience, how it is built, and its upsides and some downsides, and we highlight implications for leadership.

Two observations set the stage. The first is that the unexpected is abundant and is becoming an increasing part of the everyday. Whether you are an oil company or a healthcare institution, things that have never happened before happen all the time.3 The second observation is that complex organizations are going to continue to trip up, if only because “The systems in which we live are far too complicated as yet for our intellectual powers and technology to understand.”4 So naturally, we need to be able to cope with dangers as they arise.

Resilience: From Recovery to Adaptability

Resilience has broad appeal across and within scientific disciplines. The word resilience stems from the Latin words “resilire” and “resilio,” which mean “bounce” or “jump back.”5 Indeed, resilience has been defined and studied as an ability to recover or bounce back, to be able to absorb surprises rather than collapse. Although once thought of as an organizational capacity to deal with rare, devastating events, resilience increasingly is used to describe adaptable organizations – organizations that are able to deal with continuing, omnipresent uncertainty and risk by coping with unanticipated dangers as they become manifest.6 The idea is that in today’s world resilience is a capacity to deal with a much wider range of disruptions and disturbances that fall outside of the set of disturbances a system is designed to handle. In fact, our research has shown that a mark of resilience is the ability “to negotiate flux without succumbing to it.”2,7 Consequently more recent definitions suggest that resilience is a process by which organizations build and use their capabilities to interact with the environment in ways that positively adjust and maintain functioning before, during or after adversity.5

Resilience is not fixed, and competence in one period does not wholly predict later competence in a linear or deterministic way. Resiliently facing adversity in one period makes an organization more broadly prepared for competence in the next period, but it doesn’t guarantee it. Rather, resilience is relative, emerging and changing in transaction with specific circumstances and challenges.8

Resilience: How Do Organizations Build It?

Resilience emerges both from capacities leaders and their organizational members build and the processes that they enact. Entities survive not only because of particular endowments such as access to adequate financial, material and human resources (i.e., knowledge and expertise), but also, more importantly, because of processes that fuel abilities to dynamically interrelate with the environment. Our research2,5,8,9,10,11 shows the following elements are critical.

Capabilities: Research points to four endowment/capability building blocks.

- Financial, material and cognitive resources: Financial reserves, usable resource stockpiles and other human capability endowments (e.g., knowledge, expertise, vision, values) enable organizations to adjust to strain and maintain functioning.

- Behavioral capabilities and response repertoires: Broad action capabilities and behavioral repertoires, built through continual training, education and expanding boundaries of people’s work, fuel improvisation and recombining resources.

- Emotion-regulation capabilities: Emotional capital and collective mental fortitude/mental hardiness, as well as abilities to regulate emotions and a culture of care and collective coping (fostering a sense that we are in this together) help to diffuse and reduce anxiety arising from adversity.

- Relational capabilities: Broad and deep social connections provide access to and exchange of resources and play an important role in shaping immediate actions and ultimately enabling positive functioning in the face of adversity.

Processes: Research points to four processual building blocks.

- Communicating and coordinating: Providing structured opportunities for organizational members to speak up, voice their concerns, contribute and share observations provide means to create a rich and accurate mental model of the situation – to understand where things stand now in order to align actions with the changing context. When communicating and coordinating are haphazard, organizational members swiftly lose their shared understanding of the context, develop divergent views of what is happening, and become disoriented and disassociated from their situations.

- Relating: Create opportunities for organizational members to connect physically and emotionally in order to encourage them to collectively bear the burden of adversity. Under adversity, people often start moving away from one another at the very time they should be moving toward one another. In strengthening or reaffirming their connections to one another, organizations can disperse adversity across members, diffusing its effects.

- Meaning making: Adversity taxes organizational members’ emotional realities and the meaning of their experiences because it shatters fundamental assumptions about one’s organization, the environment and even oneself. Relating is crucial, but so too are processes of meaning management. Leaders and others must reshape and reinforce meaning to allow people to keep going. Meaning-making processes involve integrating the current adversity into a new or temporary narrative that fuels members’ momentum. This might involve changing definitions of performance and success, recrafting the organization’s identity and/or emphasizing the impermanence of the current situation.

Downsides of Resilience

Resilience certainly has its upsides in shaping organizational functioning under adversity, but this functioning sometimes comes at a cost. Three downsides come to mind.5 First, adversity often generates negative emotions, providing a clear signal that something is amiss and requires attention and action. Yet, resilience often gives rise to “positive illusions” that fuel organizational members’ optimism, energy and confidence. If organizational members are “immune” to negative sensemaking triggers, they may fail to attend to and act on signals indicating the need to change course, which will have important implications for performance.5 Second, when collectives experience a near miss and escape a pending disaster, they underestimate the danger of future similar situations and are less likely to take actions to mitigate potential risks. In other words, successfully resiling in the face of adversity can perversely lead to more risky behaviors in the future and perhaps to even more devastating consequences. Finally, resilience fuels persistence under hardship. While noble in many cases, there are situations in which persistence may be ill chosen. For example, healthcare studies show that nurses are unusually resilient, constantly creating work-arounds for daily adversities in hospitals.12 Unfortunately, this resilient performance prevents leaders from learning about the depth of organizational problems and resource constraints, and inadvertently curtails the provision of additional resources or systemic changes that would improve performance and would serve to mitigate burnout.

Adversity: A Moment of Truth

Situations requiring resilience confront us with the limits of our comprehension and with the limits of permanence. All order is transient. Impermanence is the same everywhere: Leaves fall, maidens wither and kings are forgotten.13 The experience of impermanence – that everything is shifting, dissolving, rising and falling – often leads to a clinging to what was and blindness to what is. But when humans are resilient, they emphasize what is left rather than what is lost. Indeed, the essence of human resilience is to be concerned with the future more than the past, to apply one’s abilities to boldly face the current situation and create hope that something will make sense no matter how things turn out, despite chaos, brutality, stress, worry or despair.

Adversity is a moment of truth. It is an abrupt and brutal audit of all that has been built before. It affects how much organizations stretch without breaking and then how well they recover. Some audits are mild; others are brutal. All are ultimate tests of organizational resilience. Resilience isn’t just a fixed trait or capacity, it can be built, and, most of all, it is something we do together with others.

Kathleen M. Sutcliffe is a 2024 Kenan Institute Distinguished Fellow and a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Business and Medicine at Johns Hopkins University with appointments in the Carey Business School, the School of Medicine (Anesthesia and Critical Care Medicine), the Bloomberg School of Public Health, the School of Nursing, and the Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality. She is also professor emeritus of management and organization at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business. Her contributions to the institute’s Grand Challenge focusing on business resilience provide key insights and research that help examine and drive solutions to the most complex and timely issues facing business and the economy today.

1 Figure 1 plots the relative frequency of the appearance of the phrases “organizational resilience” and “business resilience” from 1900 to 2019 (the last year for which data were available) in English-language books using Google Book’s Ngram Viewer. It illustrates a long period where the phrases never appear and shows an obvious increase in the relative frequency of the phrases since about the early 2000s.

2 Weick, K.E. & Sutcliffe, K.M. 2015. Managing the Unexpected: Sustainable Performance in a Complex World, Third Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

3 Sagan, S.D. 1993. The Limits of Safety: Organizations, Accidents, and Nuclear Weapons. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

4 Churchman, C.W. 1968. The Systems Approach. New York: Delacorte: p. xi.

5 Williams, T.A., Gruber, D.A., Sutcliffe, K.M., Shepherd, D.A., & Zhao, E.Y. 2017. Organizational response to adversity: Fusing crisis management and resilience research streams. Academy of Management Annals, Vol 11 (2), 733-769.

6 Wildavsky, A. 1988. Searching for Safety. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books: p. 77.

7 Boin, A., Comfort L.K., & Demchak, C.C. 2010. The rise of resilience. In L.K. Comfort, A. Boin, & C.C. Demchak (Eds.), Designing Resilience: Preparing for Extreme Events. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press: p. 8.

8 Sutcliffe, K.M., & Vogus, T. 2003. Organizing for resilience. In K.S. Cameron, J.E. Dutton, & R.E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive Organizational Scholarship. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler: 94-110.

9 Barton, M. & Sutcliffe, K.M. 2009. Overcoming dysfunctional momentum. Human Relations, 62(9): 1327-1356.

10 Barton, M., Sutcliffe, K.M., Vogus, T.J., & Dewitt, T. 2015. Performing under uncertainty: Contextualized engagement in wildland firefighting. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 23(2), 74-89. DOI 10.1111/1468-5973.12076.

11 Barton, M. & Sutcliffe, K.M. 2023. Enacting resilience: Adventure racing as microcosm of resilience organizing. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, Sep 2023, Vol. 31 Issue 3, 560-574.

12 Caza, B., Barton, M., Christianson, M., & Sutcliffe, K. 2021. Conceptualizing the who, what, when, where, why, and how of resilience in organizations. In Powley, N., Caza, B., & Caza, A. (Eds), Handbook of Organizational Resilience. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Press, 338-358.

13 Weick, K.E., Sutcliffe, K.M. 2006. Mindfulness and the quality of attention. Organization Science, 17(4), 514-525.