Resilience in the Age of Short-Termism

Publicly traded companies try to “underpromise and overdeliver” when reporting growth forecasts because the only thing better than getting good news is getting unexpectedly good news. The aphorism’s basic tenet – to keep expectations low and pleasantly surprise with results – applies universally across industries, from tech to hospitality to construction, and doubly so for corporations that report to shareholders every quarter. For public firms, the market rewards performance that beats expectations. To an even greater degree, shareholders punish companies that fall short of their projections. Disappointment stings, and it seems to sting more today than it did before.

The Wall Street Journal recently reported that companies that missed earnings estimates in the first quarter of 2024 experienced share price drops of 2.8%, compared with the five-year average of a 2.3% decline. Meanwhile, outperforming expectations in 2024’s Q1 resulted in an 0.9% boost in shareholder value, compared with a historical average of 1%. The article posits that pressures to perform may be particularly strong in the current moment because of high valuations and uncertainty about Federal Reserve rate cuts. These conditions may explain the half percentage point separating this year’s market responses from the historical average, but what about the normal, represented by the five-year average, which shows that the valuation penalty for a publicly traded firm to misstep is more than 2x the benefit of excelling? Does a swinging strike hurt more than a home run helps? The message this sends to C-suite executives of public companies is clear: Do not miss those expectations!

Short-Term Demands Spur Short-Term Thinking

Attributing greater value to a shortfall than to overperformance reflects the market’s “loss aversion” – our tendency to be more sensitive to losses than to gains of equal magnitude – yet this phenomenon also signals a long-term economic trend toward short-term demands and rewards. Companies that must answer to public shareholders every few months are incentivized to make investments with immediate payouts.

What if a firm wishes to make investments that will be costly in the near term yet could foster long-term growth? The firm’s executives could provide guidance downgrading their near-term outlook. Netflix recently tried that and learned a hard lesson. After beating expectations in the first quarter of this year, Netflix gave softer-than-expected guidance for the second quarter and was promptly punished with a 9.1% drop in share price. What would have happened to the share price if Netflix had revealed plans to invest in resilience-building measures, such as greater streaming redundancy and technologies that lower the likelihood of security breaches, instead of in new content and initiatives? The company’s shareholder value likely would have taken an even greater hit for making moves that would increase long-term resilience but do nothing to increase profits today.

Short-Term Thinking Exacerbates Risk, Reduces Resiliency

Technological advancements, such as the advent of algorithmic trading, have helped entrench and amplify short-termism, yet it is not a new phenomenon and, among the private sector, not merely driven by public investors. As part of our 2022 Grand Challenge exploration of stakeholder capitalism and ESG investing, we presented research finding that agency problems that drive a wedge between management and shareholders and operational challenges, such as trouble defining clear and measurable long-term goals – in addition to transient investors’ pursuit of short-term profits – prevent management from focusing on long-term benchmarks and pursuing resilience-building measures. This is a problem because, as described in our article introducing this year’s Grand Challenge, the pace of change has accelerated, and we are in a period of high uncertainty. Firms face myriad potential hazards and accompanying risks, including geopolitical flare-ups that disrupt supply chains, regulatory changes that tilt the playing field, and rapid technological developments that suddenly reshape industries and consumer expectations. Without knowing precisely what gauntlet lies ahead, how can a company build resilience in the face of such pervasive risk?

The answer is investment. To respond to artificial intelligence technology disruption, companies should spend money on training their workforces to use the new tech. As geopolitical tensions, environmental hazards and regulatory burdens threaten to strain supply chains, industry actors may have to invest in vertically integrated measures to build resource resiliency. Meanwhile, R&D investment is the germ of innovation and the source of the next disruptive technology promising productivity gains and long-term profits. Building resilience to the risks of tomorrow demands more than money – it requires time spent learning, thinking and strategizing about how one’s business should approach a particular issue, whether it’s effectively integrating AI, responding to reputational challenges or finding young talent to replace a soon-to-retire workforce.

In many cases, these investments have short-term costs but offer long-term gains – considering that costs include not only the actual spending on a new technology but also the time spent learning to use the new technology. Healthcare providers, for example, have begun integrating AI applications with their electronic health records systems, which requires an upfront investment in the computing technologies and training of their staff. A recent industry survey found that, on average, the new systems pay for themselves in efficiency gains after 14 months – not very long-term at all. The markets are enamored with AI, so perhaps long-term AI-related investments will get a pass from those demanding near-term growth. Yet how will markets value the opportunity costs and management time involved with strategically planning those investments and associated worker training? And what about other R&D initiatives, those that do not have the AI moniker?

Much of the money and time spent on risk avoidance and mitigation is costly to implement and may never show tangible returns beyond survival or outperformance – the hallmarks of resilience – when other firms fail. A firm with too great a focus on near-term returns is likely to discount future risk, and, even when the risk is acknowledged, short-term thinking would make the company less inclined to invest in mitigation.

At a recent business roundtable discussion on business resilience featuring Kenan Institute Distinguished Fellow Kathleen M. Sutcliffe, several C-suite executives noted that their companies’ cyber mitigation philosophies amounted to building a wall one brick higher than cyberattackers could climb. This would be a smart decision if one were confident in how high such criminals can climb, but a spate of successful attacks on key infrastructure demonstrates that no one knows just how high to build the wall. The idea that a firm should safeguard its data only to the extent that it would thwart a would-be thief and no more epitomizes the short-termism paradigm: Once the marginal cost of the proverbial wall’s bricks exceeds the opportunity cost of near-term returns, short-term thinking dictates a halt to bricklaying. If public markets were to reward long-term risk-mitigating activities, investment in preventing cyberattacks, for one, could innovate lasting solutions to the problem, building sturdy infrastructure rather than using a brick-by-brick approach.

R&D Investing and Productivity Stagnate

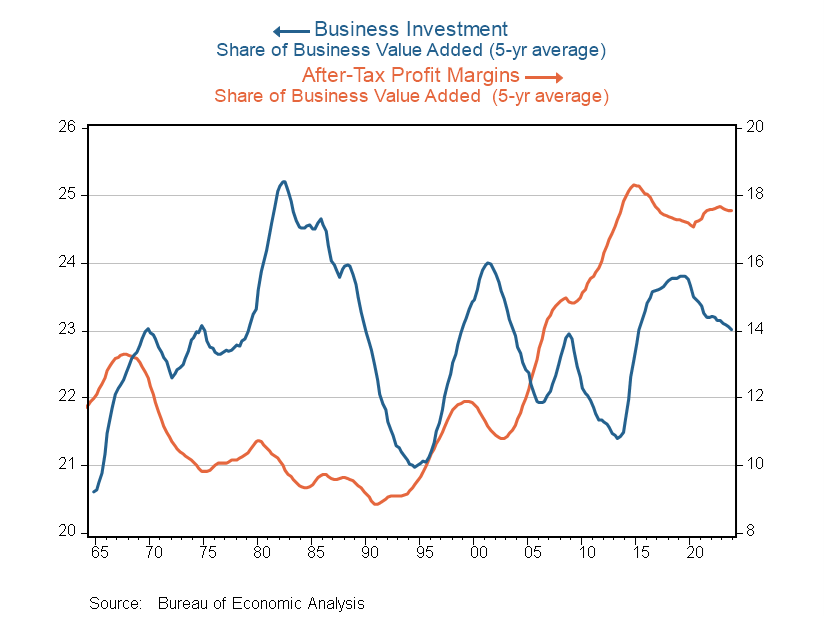

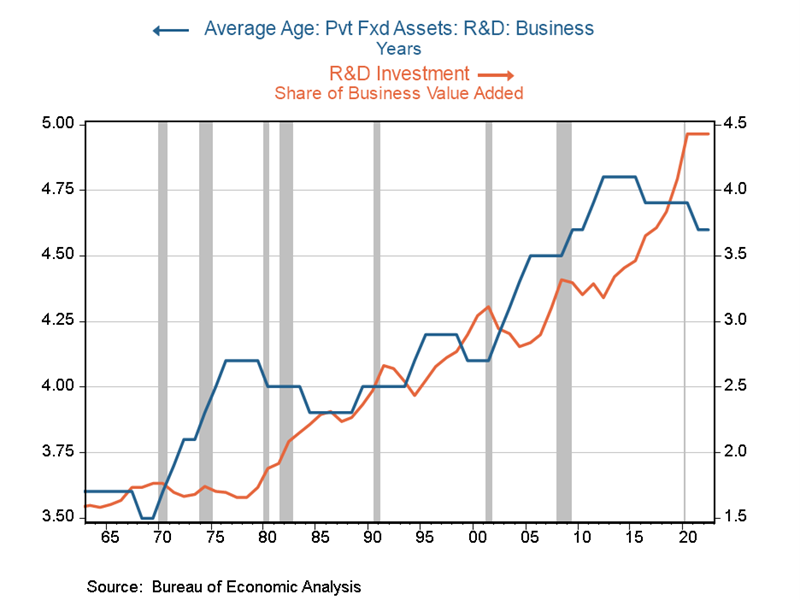

It is difficult to measure business resilience, yet we have proxies for spending on resilience-building measures. Corporations have had healthy profit growth for the past several decades and, more recently, robust corporate profit margins, yet business investment’s share has remained around historical averages. This discrepancy suggests that companies are returning capital to investors rather than in R&D and other investments that would build long-term resilience. Digging deeper, R&D investment, which is a proxy for resilient capital, has been rising for decades, though it has remained flat since 2020 and is a relatively small share of business spending. Meanwhile, R&D-related capital stock – i.e., servers and lab equipment – has, until recently, been aging. This data suggests that while businesses are spending more of their income on R&D, they are not keeping abreast with this type of investment’s fast depreciation rates. Kenan Institute Distinguished Fellow Josh Lerner supported this notion, as he observed that large American firms are investing less in R&D, with the decline concentrated in research (as opposed to development) expenditures.1

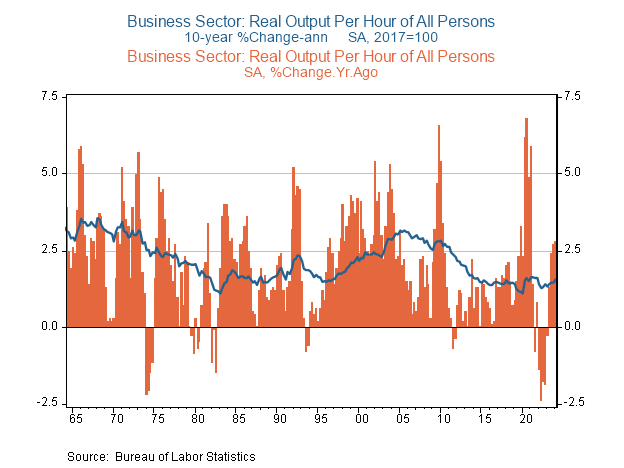

It is challenging to know whether this trend reflects firms’ enhanced abilities to leverage shared resources such as Amazon Cloud Services to create capital-light businesses or whether it shows the deleterious impact of short-termism. Business productivity is a key metric speaking to the effects of lackluster R&D investment, and this indicator has been weak over the past 10 years, growing at a sluggish 1.5% annual rate (it grew at more than double that pace in the 10 years ending in 2005). This metric has shown a slight uptick in the past year, and economists are wondering whether the recent productivity gains reflect the payoff from investments made years before or if it is merely part of post-pandemic volatility. If this year’s modest boost to productivity turns out to be cyclical, the prevalence of short-termism will not help reverse 20 years of tepid productivity growth.

A Healthy Balance Between Short- and Long-Term Thinking

There are, of course, caveats when we try to neatly frame a short-term versus long-term paradigm. If short-termism is the impediment to building business resilience, does that mean long-termism is the key to building business resilience? Yes and no. In the 1980s, the Japanese model, which featured long-term planning, lifetime employment and “keiretsu” – a close relationship between companies and banks2 – was hailed as the future of business. This attention fueled an equity and real estate bubble – at one point the 1.3-square mile Imperial Palace in the heart of Tokyo was worth more than the entire state of California3, and the Nikkei stock index rose to unprecedented levels in 1989 that were only surpassed in February 2024. Then in the early 1990s, the price bubble burst and Japan’s economy entered a prolonged period of stagnation. One of the lessons from the Japanese bubble – and many bubbles – is that some short-termism is warranted and even healthy. Japanese companies were very flexible in some ways, investing in their workforce with workers granted lifetime employment, but were brittle in others, as these firms were unable to shed workers during the structural downturn.

As with other areas related to economics, there is an appropriate balance, an efficient equilibrium, between short-term and long-term thinking. Being beholden to investors and being penalized for not performing ensures that companies are focused on their bottom line and that they think strategically about their investments. Yet if too much attention is given to next quarter’s returns, it shifts a firm’s gaze toward the immediate, blinding it to long-term risk. The rise of short-term thinking has exacerbated this effect, reducing the resiliency of some firms and industries. In fact, quarterly reporting, with its carrots and sticks, may be the reason why more companies are going private – research suggests that private ownership allows for greater long-term planning and investment than does public ownership. Our next Grand Challenge piece on the theme of resilience tries to find this balance by quantifying some of the uncertainties businesses face and suggesting ways in which management of both public and private companies should respond.

This article about the rise of short-termism and its effects on investment and resilience is part of our Grand Challenge series on business resilience.

1 Arora, A., Belenzon, S., & Sheer, L. (2021). Knowledge spillovers and corporate investment in scientific research. American Economic Review, 111(3), 871-898.

2 https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1164&context=jgi

3 https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/japans-crazy-1980s-bubble-dim-memory-nikkei-hits-record-high-2024-02-22/#:~:text=The%203.4%20square%20kilometres%20(1.31,roughly%2040%25%20of%20annual%20GDP