Examining the pandemic fallout and looking toward the future.

By Jessica Wilkinson

Economic Development Manager, NCGrowth

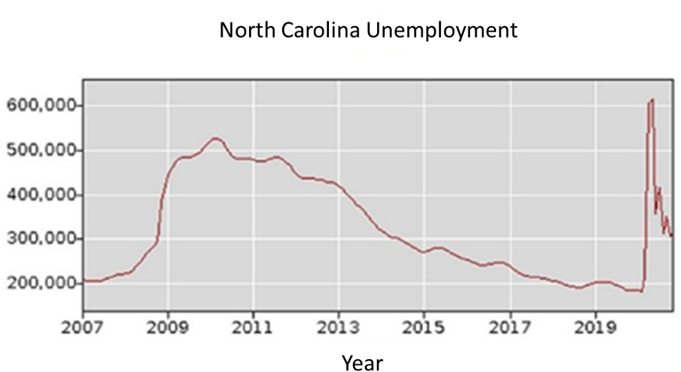

2020 brought an end to North Carolina’s decade-long economic expansion that began in 2010 after the Great Recession. It has now been a year since COVID-19 arrived on U.S. shores, and we can see some changes clearly, while others are just starting to emerge from the haze. It will likely be years before we fully grasp the myriad ways COVID-19 has affected the nation’s and the state’s economies. Now seems like a good time to take stock of the fallout from 2020, the trends we’re seeing a year into the crisis and where things are starting to turn around for North Carolina.

What happened?

- Before the pandemic struck in early 2020, North Carolina was in the middle of experiencing a historically low unemployment rate of 3.6 percent. As we now know, the unemployment rate rose to shockingly high levels shortly after COVID-19 reached our shores. This was largely due to state and local government public health policies aimed at curbing infections, and decreased consumer confidence. At the height of the economic shutdown in April and May, the unemployment rate among North Carolina residents was 12.9 percent, higher than at any point during the Great Recession. Although the unemployment rate has since decreased to 6.2 percent (as of December 2020), it remains higher than it was prior to the start of the pandemic.1 Compared to other states, North Carolina’s unemployment rate was the 29th lowest in the nation.

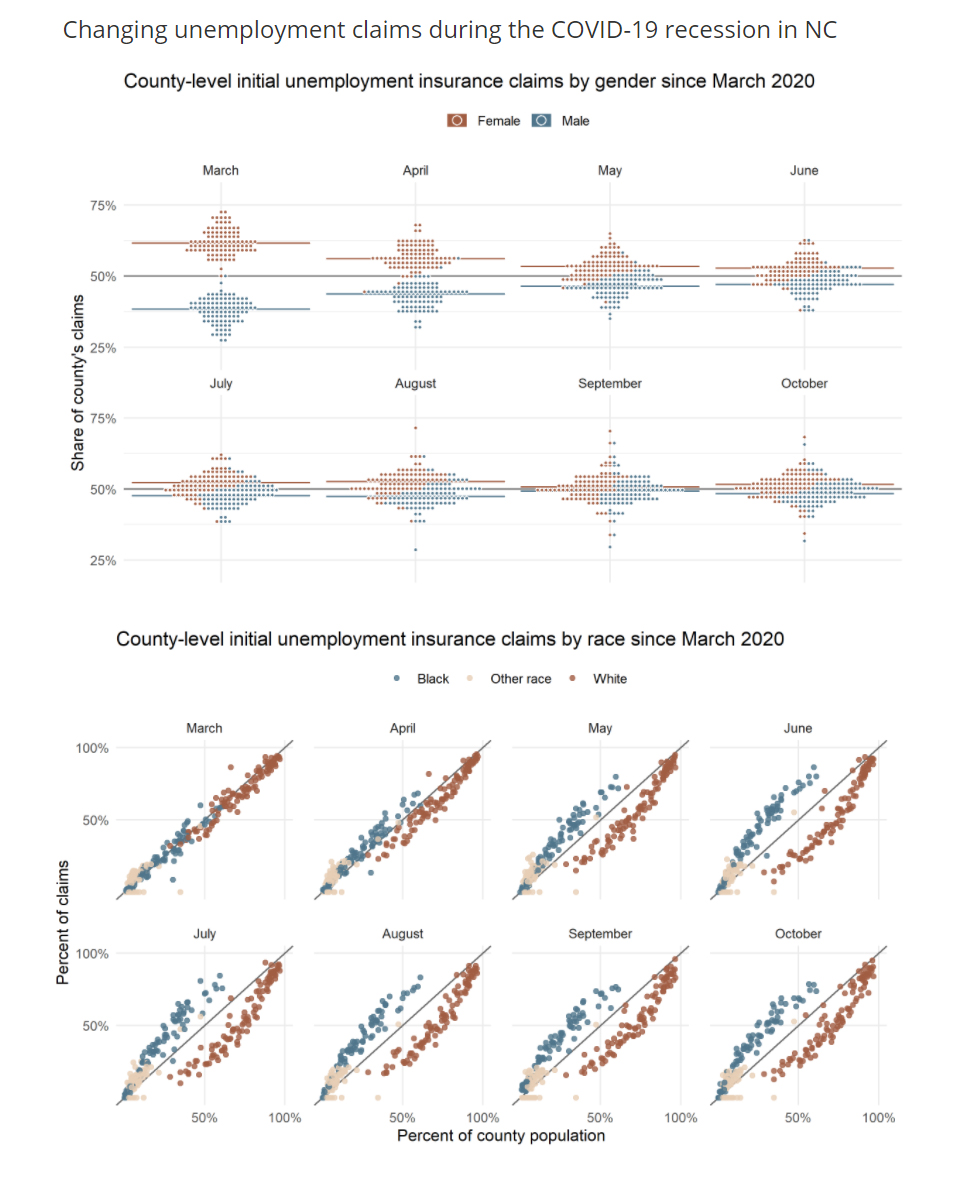

- Although we don’t yet have state unemployment rates broken out by gender or race, we do have county-level unemployment insurance claims data broken out this way. This data shows that women filed disproportionately more unemployment insurance claims at the beginning of the pandemic. However, this gap closed during the summer and fall.2 While the gender gap narrowed, the racial gap in unemployment insurance claims widened. In the graph to the right titled “County-level initial unemployment insurance claims by race since March 2020,” the black diagonal line is where a dot (representing a county’s unemployment insurance claims) would be if the number of unemployment insurance claims for that county’s racial category were proportional to the percent of county residents identifying with that category. Dots above and to the left of the black line represent disproportionately high unemployment insurance claims in that county. For most North Carolina counties, Black residents filed disproportionately high numbers of claims compared to their white counterparts.

- As stay-at-home orders have phased out, businesses and communities are navigating, with little guidance or research, how to reopen in ways that protect the health of their employees and customers. As such, there is no simple “how-to” guide for how governments and businesses should respond to the economic impacts of COVID-19 or how to strategize for a post-COVID future. Many local governments are looking to examples set by their peers for guidance and inspiration on crafting a local response.

- In the early months of the pandemic, many state and local governments and private entities across North Carolina offered support for workers and business owners in the form of technical assistance, information sharing, loans and grants. Although the webinars and technical assistance persist, most sources of funding have dried up.

- Rural counties felt COVID-19’s effect on unemployment sometimes months before they felt its health effects. As of March 16, 2020, COVID-19 cases were only in concentrated population centers; however, unemployment claims were comparable across both urban and rural areas.

- According to an October 2020 national Lending Tree report examining consumer spending, small business revenue, job postings and the unemployment rate, North Carolina ranked 10th among states in rate of recovery from the pandemic.3 The North Carolina Department of Revenue reported that every sales tax category is up for August 2020 compared to August 2019. Some business owners speculate that the rise in spending comes from people spending money locally rather than on vacations and travel.

- Despite the pandemic, a number of large companies announced plans in 2020 to open up shop in the state. In November, Clorox announced that it plans to bring 158 high-paying jobs to Durham, In the same month, Chick-fil-A announced its plans to open a large distribution center in Mebane, bringing 160 jobs to the town. In mid-December, Texas-based Taysha Gene Therapies announced that it will open a manufacturing operation in Durham. This venture represents $75 million in capital investment and 201 high-paying jobs with an average wage of $119,751.

Looking forward to 2021

- In general, economic experts across the state are looking toward 2021 with optimism. In recent news reports, Chris Chung, CEO of the Economic Development Partnership of North Carolina, has noted that EDPNC is monitoring 180 active projects statewide, representing 39,000 new jobs and about $11 billion in investment. December 2020 brought 24 new project proposals, ten more than the previous year.

Adapting our strategies for economic development

- As the health and economic effects of the pandemic continue to play out in unpredictable ways, researchers and policymakers will likely find it difficult to offer long-term strategies for economic growth.

- Prior to the onset of COVID-19, the North Carolina Department of Commerce was in the process of developing an updated multi-year economic development strategy. Originally expected in April 2020, the agency’s website now says it will “publish a new strategic plan for economic development later this year that will guide policymakers and practitioners in their work to bring more economic prosperity to the state.” The website does not include an updated release date for the strategy.

- The economic development recommendations outlined in the NC Tomorrow plan released in 2017 remain relevant and general enough to benefit the North Carolina’s communities despite 2020’s challenges:

- Build on the Region’s Competitive Advantage and Leverage the Marketplace

- Establish and Maintain a Robust Regional Infrastructure

- Create Revitalized, Healthy, Secure and Resilient Communities

- Develop Talented and Innovative People

- According to the plan, economic developers and policymakers should target the state’s “growth clusters.” Indeed, some of these clusters grew in 2020, and some of these clusters operate “essential services,” a term that took on a completely new meaning with the arrival of COVID-19. Although they certainly experienced challenges in 2020, industries such as life sciences, pharmaceuticals, manufacturing, energy, food processing, transportation equipment and financial services all experienced a pandemic-related boom. The only industry listed by the NC Tomorrow plan that took a significant hit due to the pandemic is tourism. However, outdoor recreation, a part of tourism, saw huge growth in 2020. Further, tourism may experience a spike once more people receive their vaccinations or COVID-19 infections begin to subside.

In all, 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic brought with them shockingly high unemployment rates, but only for a short period. Unemployment rates are now at “precedented” levels again, but are still twice as high as they were at the beginning of the pandemic. Emerging but unsurprising data show that racial disparities persist when looking at key economic indicators such as unemployment claims. Economists often say that recessions create winners and losers. However, they don’t usually call attention to how this plays out along racial lines, with Black people and other people of color generally experiencing harsher economic outcomes compared to white people. The truth is that this has been the reality recession after recession. In 2021, we will continue to look toward policymakers, academics, industry leaders and ourselves to see how we finally attempt to break the cycle.

As a whole, North Carolina looks poised to make real strides toward recovery in 2021. The state’s unemployment rate isn’t nearly as high as that of some states. And existing economic development strategies like the 2017 NC Tomorrow plan still seem relevant, even after one of the most bizarre and difficult economic years on record, indicating that its strategies are long-term, diversified enough and resilient.

ANNUAL 2020 NC ECONOMIC REPORT

1 “Bureau of Labor Statistics Data,” accessed January 27, 2021, https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LASST370000000000003?amp%253bdata_tool=XGtable&output_view=data&include_graphs=true.

2 Kaitlin Heatwole and Ethan Sleeman, “Widening Racial Disparities in Unemployment Claims,” Carolina Tracker, accessed January 27, 2021, http://carolinatracker.netlify.app/stories/2020/10/05/ui_claims/.

3 “Economic Recovery Amid Pandemic Strongest in Idaho, Kentucky, Kansas,” LendingTree, accessed January 27, 2021, https://www.lendingtree.com/debt-consolidation/economic-recovery-study/.

COVID Ended a Decade-long Economic Expansion in North Carolina. Now What?