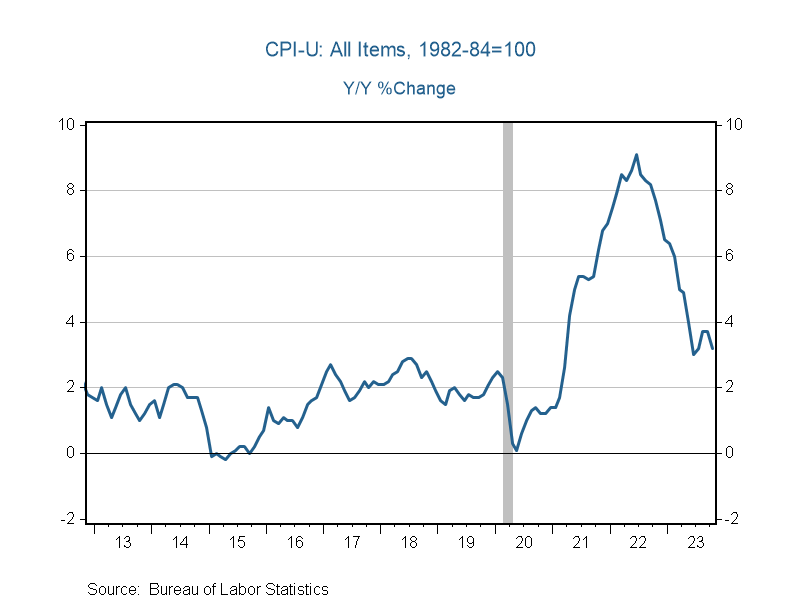

Chairman Jerome Powell and the Federal Reserve policymakers must be pretty happy with the most recent inflation report, which showed that the U.S. inflation rate fell to 3.2% in October, compared with a 12-month rise of 3.7% in consumer prices in September.

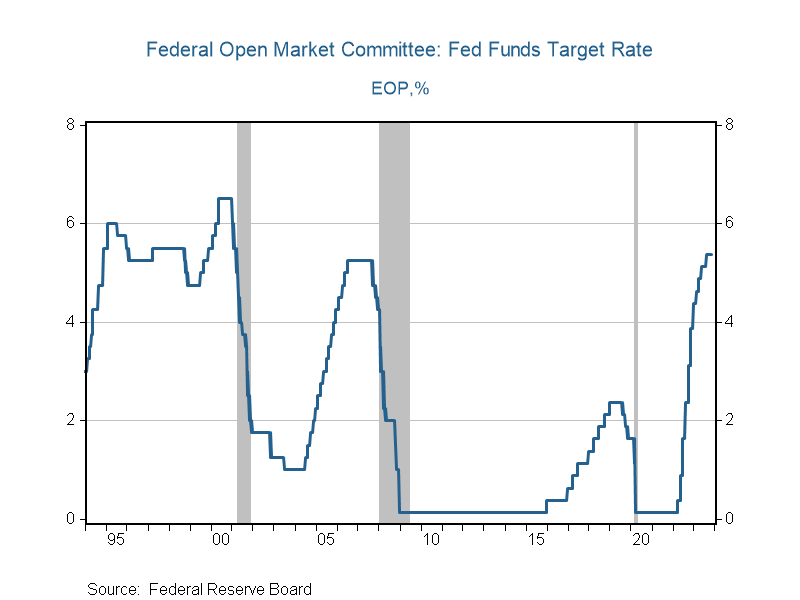

This inflation report is certainly comforting news to the Fed. Since March 2022, the U.S. central bank has battled the highest inflation in decades. The Fed steadily increased its benchmark rate at the fastest pace in more than 50 years, from around zero in March 2022 to 5.25%-5.5% in July 2023, and has kept the benchmark rate steady at that level, a 22-year-high. Despite the rate hikes, the economy largely continued to forge ahead, defying most analysts’ expectations, maintaining a sub-4% unemployment rate with healthy GDP growth and consumer spending. It is only now that the hot economy is showing some signs of cooling, and that finally may be good news.

The latest Labor Department numbers show small signs of the job market cooling, as hiring slowed in October, and the unemployment rate ticked up to 3.9% from 3.8% in September, up from its low of 3.4% in April. Slower hiring was accompanied by dampened wage growth, which slowed to its lowest level since June 2021. Other indicators point to the pandemic-relief economy being long over, as credit card delinquencies rose to their pre-pandemic levels, up from historic lows during the pandemic. And perhaps the most gratifying of all news for the Fed is the continued progress on inflation: Price pressures have eased markedly.

So, is the interest rate cycle over? Investors are already declaring it the end of the era of rate hikes. Immediately after October’s inflation report, markets put the chance of the Fed raising its policy rate any higher at only about 5%. Investors appear to expect a rate cut by May of next year.

Since earlier this month when he announced the decision to keep the benchmark rate steady for a second time, Powell has struck a cautious tone and suggested that he believes monetary policy still has work to do. It is not surprising that the Fed would want to err on the side of rate-hike hawkishness after facing persistent high inflation. Yes, the inflation rate is down to 3% from its peak level of 9% a year ago, but the Fed still would like to see inflation neatly back at its goal rate of 2%. The Fed has rightfully worried that continued signs of strength in the economy would produce nasty surprises, threatening recent progress on inflation. The recent inflation report should help ease those worries some. The markets may be showing optimism that we have arrived, yet the Fed will surely need more evidence before rate cuts appear on the horizon.

It is smart to take stock of the current state of affairs of the whole economy and not cherry-pick economic data.

While there are some signs of a softening economy – jobless claims, for instance, have trended up in the past few weeks, and the Institute for Supply Management surveys of manufacturing and services activity showed weakening in those sectors – not all data point in the same direction. It is yet to be seen whether the uptick in the unemployment rate is truly a slowdown in job creation or simply driven by an increase in the size of the labor force as more people return and have not yet found jobs. After dropping significantly, the labor force participation rate has still not recovered to its pre-pandemic level. Meanwhile, the ISM’s manufacturing measure contradicts S&P Global’s manufacturing survey, which indicated stable conditions for U.S. manufacturing activity in October. From a bird’s-eye view, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow growth estimate is tracking 2.1% growth for the fourth quarter – hardly a slowdown.

A key question is what does the Fed estimate for the long-run neutral rate – the interest rate that neither stimulates nor suppresses growth. Unfortunately, the neutral rate cannot be observed directly but can only be estimated looking backward. It is plausible to look at the most recent period, in which the Fed raised interest rates over 5 percentage points alongside strong real GDP growth and consumer spending while the unemployment rate remained below 4%, and to argue that the neutral rate must be higher than its pre-pandemic level. High uncertainty in measuring the natural rate makes policymakers less inclined to heavily rely on it for guiding monetary policy. If inflation continues to fall while the Fed funds rate remains constant, however, it means that inflation-adjusted short-term interest rates are rising, which is certain to increase the pressure on the interest rate-sensitive parts of the economy.

Then there is the matter of long bond yields. About a month ago, the yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury note touched 5% – a 16-year high. Even after dropping sharply to around 4.44% following the inflation report, the long-term bond yield remains significantly higher than where it was before the summer – when the ratings agency Fitch downgraded U.S. sovereign debt and Moody’s lowered its outlook on the U.S. credit rating from “stable” to “negative.”

Higher yields on long-dated bonds may have allowed the Fed to rest a bit easier by doing the job of tightening financial conditions. Yet the term premium – the extra compensation that investors demand for holding longer-dated investments – that is driving the rise in long-dated Treasury yields may point to greater trouble ahead: fears around fiscal sustainability, large chronic budget deficits, and investors’ limited willingness to view these conditions to be a sustainable path. The higher-term premium may in fact be what investors require because they are worried that eventually the Fed will have to resolve the deficit issues by monetizing the debt. This might be the real future trouble at hand.

The U.S. is now facing rising and increasingly expensive federal budget deficits in a high-interest-rate environment – at least for now – which means debt servicing is going to take up a growing share of public spending. The U.S. Congress, with its perpetual stalemate, should take notice.

The Fed and Inflation: Are We There Yet?