Consumer Power in the Age of Plastics

Stakeholder capitalism discussions frequently focus on the behavior of businesses – and pay less attention to the consumer. This disparity may, in part, be due to a general discounting of consumers’ agency within the stakeholder framework. Given that producers of goods and services tend to drastically outweigh individual consumers in both spending and market power, one may rightly wonder whether individual buyers have any ability to effect real change. Even the most concerned consumers may feel disempowered or else unable to access accurate information around how to change their purchasing habits.

A single plastic product takes roughly a few hundred years to fully decompose; as it does so, it gradually releases millions of miniscule microplastics that are eventually present throughout the natural and human environment.

And yet, the 20th century is rife with examples of consumer advocates moving the needle on important societal issues. Muckrakers in the Progressive Era were able to push for some of the first consumer protection laws, outcry over the health impact of cigarettes led to substantial decreases in smoking rates, and the work of individuals such as Ralph Nader led to safer automobiles. It is thus clear that concerted action on the part of the public can cause even the most powerful of lobbies to acquiesce to its demands. But the question remains: What are the mechanisms for consumer-driven change?

We examine this larger topic of consumer power through the lens of plastic consumption. Plastic goods carry large, global negative externalities. A single plastic product takes roughly a few hundred years to fully decompose; as it does so, it gradually releases millions of miniscule microplastics that are eventually present throughout the natural and human environment. As a material, plastic is firmly integrated into products across virtually every consumer goods sector, making its entrenchment seem even more unshakable. Moreover, much of the public is under the impression that plastic products are recyclable when only a small percentage of plastic waste actually is reused. Given the ubiquity of plastic and the size of the problem, consumers may rightly ask what power they have as stakeholders to bring about effective change.

Despite these obstacles, individuals can use their power as consumers to address the problem. Below, we draw on models of consumer behavior to demonstrate ways in which one can, in fact, exercise one’s market power to build toward real change. On an individual level, we can change our framing from recycling-focused to reducing- and reusing-focused; on a collective level, we can push for change in our communities and promote regulatory action. The takeaways described can serve as a model for how we can use our power as buyers of goods and services.

The Myth of Recycling Plastic

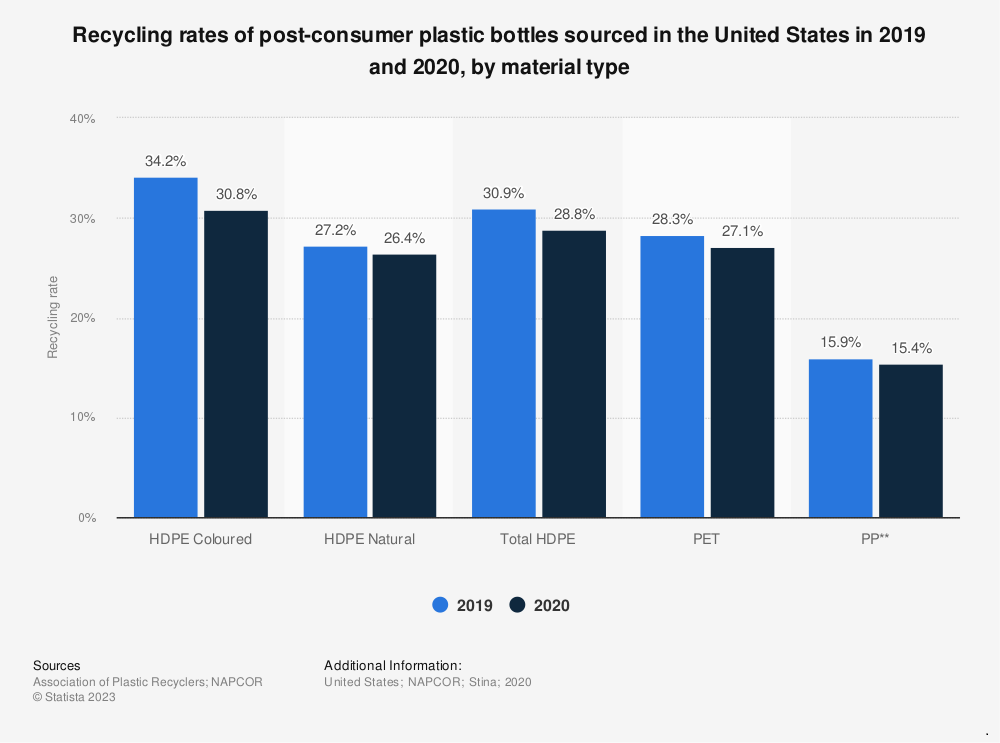

Many of us operate under the assumption that our soda cans, plastic grocery bags and takeout containers are environmentally friendly; if we dispose of them in the blue bin, we aren’t hurting the planet. Unfortunately, this turns out not to be the case, as was documented in an October report from Greenpeace. While the United States produced an estimated 51 million tons of plastic waste in 2021, Greenpeace’s analysis found that only 2.4 million tons of this plastic – a little under 5% – was actually recycled.

Apathetic consumers are not to blame for this disparity. A 2022 survey found that roughly 62% of U.S. adults reported that they recycle most or all of their household’s plastic waste. And, despite 86% of adults believing the U.S. plastic recycling process needs improvement, our recycling management systems aren’t the culprits, either. The problem lies with plastic products themselves, which are far less recyclable than one might think. As an oil industry insider acknowledged in a 1974 speech, “there is serious doubt that [recycling plastic] can ever be made viable on an economic basis.”1 In the 50 years since that statement, little has changed in how we recycle that would alleviate this doubt.

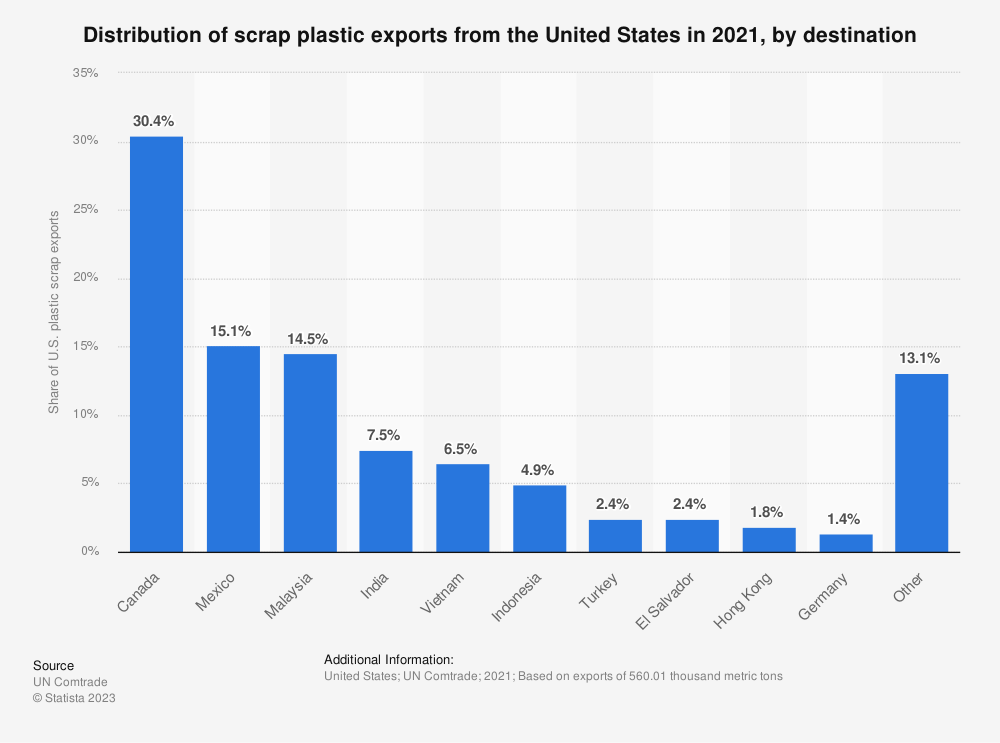

In reality, the U.S. and many other developed nations tend to export plastic waste to other nations’ landfills. Until recently, the recipient was usually China, which received roughly 7 million tons of plastic a year.2 However, in 2017, China imposed sharp restrictions on plastic trash imports before instituting a complete ban of the practice the following year. Rather than eliminate U.S. waste exports, however, these regulations have merely changed where the plastic waste goes. The U.S. now sends most of its plastic scraps to countries in southeast Asia, such as Malaysia and Thailand3, as well as its continent mates, Canada and Mexico.4 These bits of plastic then end up in landfills or bodies of water overseas.

Recycling as plastic management has been a failed experiment – partly due to the cost and pragmatic difficulty of recycling. Plastic degrades each time it is used and so can only be reused once or twice even when recycled properly. The wide range of plastic items and different processes required for each means that waste companies must undergo the labor-intensive work of sorting and separating plastic into categories before it can be processed. By contrast, waste companies and consumers can quickly and easily dispose of the plastic in a landfill. New plastic, made from oil and gas, is cheap and quick to produce and usually results in higher-quality products.

Moreover, the actual environmental impact of plastic has been understated. The decision of developed countries to ship plastic waste overseas often leads to mismanagement of this waste, due to a more lenient regulatory environment and fewer waste management resources in the destination country. Mismanaged plastic waste often ends up in rivers, which inevitably results in plastic waste eventually reaching oceans and affecting water systems worldwide.

As a piece of plastic decomposes, it generates millions of tiny microplastics that enter our water supply and affect ecosystems and natural habitats across the globe. The release of these microplastics can occur over a few hundred years, meaning that a single item can be releasing poisonous materials into the environment for centuries. These negative health and environmental effects are largely the result of chemical additives that are known to be endocrine disruptors, and are associated with cancers, birth defects and immune system suppression in humans and wildlife.

The Power of the Consumer: Replacing ‘Recycle’ With Reduce and Reuse

If recycling isn’t an option, what, if anything, can consumers do to tackle such a large problem? While the scope of the plastic waste problem is far too large for anyone to tackle by oneself, there are changes in daily consumption habits that can be implemented in order to lessen our overall environmental impact. Largely, this revolves around changing the framing with which we view our personal use of plastic goods. Rather than viewing an item based on its ability to be recycled, we can achieve greater impact by reducing our total consumption of plastic and reusing the plastic we do purchase.

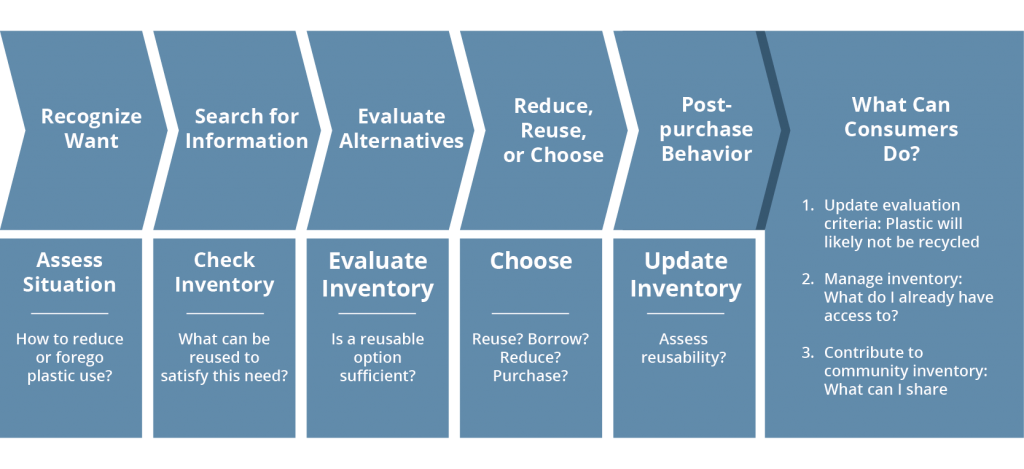

The typical model of consumer decision-making spans five discrete stages: Need Recognition, Information Search, Evaluation of Alternatives, Purchase Decisions, and Post-Purchase Behavior. According to this model, consumers initiate the decision-making process after recognizing that they lack or need something. The item in question can include either essential needs (such as groceries) or nonessential needs (such as entertainment devices). Either way, it sets the consumer down a path of determining the options available to them on the market and then choosing one of these options. Each of the other four stages offer avenues for market-based change; Table 1 below also offers a variety of alternatives for effectively changing to a framework of reducing and reusing plastic.

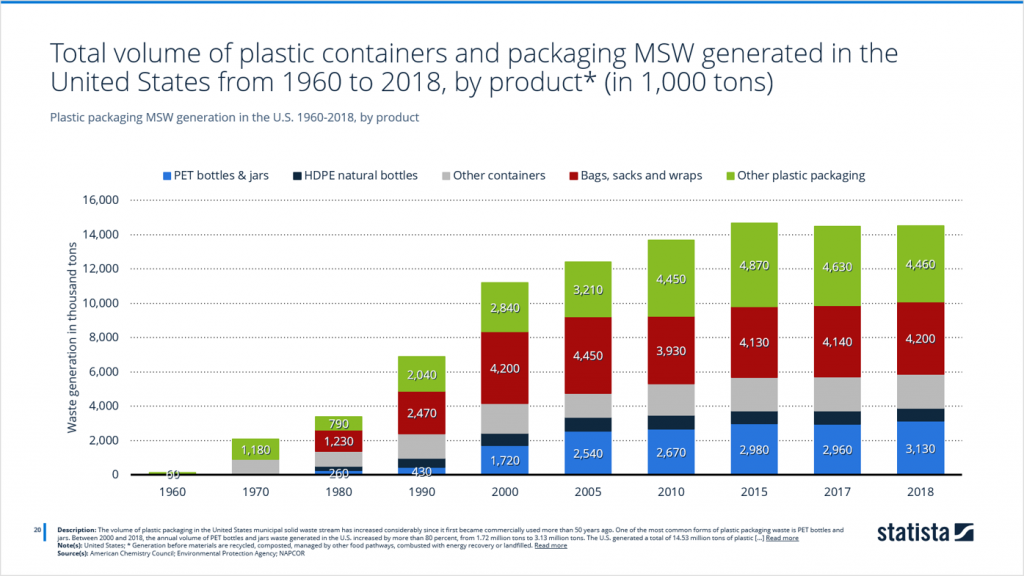

Informationally, it stands to reason that consumers would first do well to know which types of plastic generate the most waste. The two largest culprits in the U.S. are 1) bags, sacks and wraps, and 2) PET containers. The former category includes resealable bags, grocery bags and thin films used for sealing containers, while the latter refers to anything made with PET – a clear, lightweight plastic that is used for virtually all bottles of carbonated soft drinks and water. These two categories generate 4,200 and 3,130 thousand tons of waste, respectively.5 In addition, single-use plastics such as straws, bags and food containers constitute about 40% of all plastic waste.6

Knowing the largest contributors to plastic waste is one thing, but what alternative actions can consumers take? Table 1 below outlines possible alternatives for commonly used plastics, different alternatives for those specifically facing monetary or time constraints, and ideas for how to effectively change one’s personal practices. The psychological burden associated with changing a habit has been shown to require significant time and retraining; as a result, making systems that are highly actionable are more likely to result in lasting lifestyle changes.7

These alternatives include making different buying decisions that eschew plastic in favor of other products made with more environmentally friendly materials. This won’t always be possible, however –the convenience and low cost of many plastic-based goods means that we likely can’t eliminate all such purchases from our budgets. In those instances, the most effective post-purchase decision a consumer can make is to reuse the item as many times as possible. This can include rinsing and reusing plastic bags, turning old single-use beverage containers into planters, or using old containers for storage. Research has also found that using reusable cutlery, water bottles and other food-related items are the consumer actions associated with strongest environmental impact.8

Strength in Numbers: Communities as a Vehicle for Change

However, these personal actions are not enough to change the direction of plastics consumption on their own. They may buy us more time by lessening our overall impact, but the size of the issue requires quicker and more systemic change than individual consumers can provide on their own. Moreover, it’s unrealistic and unfair to expect individuals to be able to reverse a societal problem on their own. It may not be possible for many of us to entirely cut plastic out of our lifestyles – and the burden of doing so is particularly onerous for those facing financial, emotional or other constraints.

Modified Consumer Decision Making

It follows that deeper change will emanate from wider, communal action within our communities and political arenas. On a community level, people can come together and organize events such as beach cleanups, as well as push for changes within their groups, workspaces and social circles. Communities can also augment reusability options through the creation of plastic drop-off programs or rinse stations that properly clean plastics for recycling. Some of these actions, such as the work of the nascent Polypropylene Recycling Coalition, have already improved access to recycling such materials, increasing the amount of recycled polypropylene by an estimated 25 million pounds.9 Other consumer-led efforts have led to plastic straw bans and increased usage of metal or paper drinking materials.10

Additionally, as consumers move to more environmentally friendly alternatives, they also can signal their appetite for such products to companies and brands – which can, in turn, spur further supply-side development and focus on greener items. Without the necessary demand from consumers, there is little incentive for companies and waste management entities to clean up their practices. Individual actions can thus aggregate to effectuate change on a larger scale, but only if firms are sufficiently pressured by market forces.

Table 1: Alternatives to Plastic Use

| Single Use Plastics | Ideal Current Alternatives | Time-Sensitive Alternatives | Financially Sensitive Alternatives | Consumer Behavior Shift |

| Plastic Grocery Bags | Reusable bags, cloth bags, insulated bags | Reusable bags, cloth bags, insulated bags | Reuse single-use bags. Use durable bags. | Store bags in vehicle or with your shopping list. |

| Drinking Straws | Drink from the container. Use silicone or metal straws. | Dishwasher-safe silicone or metal straws | Only use straws when it is necessary. | Maintain a case to store the straw and cleaning brush. |

| Eating Utensils | Switch to biodegradable, wood or metal. | Switch to biodegradable, wood or metal. | Carry metal utensils from home. | Keep clean and dirty utensils separate. |

| Liquid Soap | Soap sheets, bar soap | Soap sheets | Bar soap | Keep the soap in all bathrooms at home. |

| Plastic Cups | Glass, beverage- and temperature-specific thermoses and cups | Dishwasher-safe flask or thermos | Reusable flask or thermos | Use the dishwasher if you have one. |

On a political level, individuals can come together to advocate for regulatory changes, which will ultimately create the largest impact. Developed countries were able to offload their plastic waste to China until the state banned the practice; if such bans were present around the globe, waste management companies would have to find other means of disposal. This is but one illustration of the need for concerted and coordinated governmental action and the rapid behavioral change it can bring about.

One final note: As discussed in a previous Kenan Insight11, entrepreneurs and innovators can play a significant role in expanding the menu of options available on the market. As consumers have become more concerned about the environmental impact of their purchases, some startups have begun finding new ways to reuse plastic and “upcycle” existing plastic waste into valuable products.12

Conclusion

It is difficult not to feel overwhelmed by the sheer amount of plastic waste generated already, or by the universe of single-use items in circulation. However, consumers are not completely powerless to begin moving the needle through personal lifestyle changes. When those lifestyle changes are combined with collective action in one’s community or political environment, real change becomes more than conceivable – it becomes possible.

Many of the takeaways from the example of plastics can apply to other situations in which individuals may feel powerless against large and entrenched issues. By integrating actionable possibilities for the consumer with larger-scale collective action, we can begin to tackle societal problems that seem too overwhelming to handle.

Appendix 1. Distribution of scrap plastic exports from the United States in 2021, by destination

Appendix 2:

Appendix 3:

1 Sullivan, L. (2020, September 11). How Big Oil Misled The Public Into Believing Plastic Would Be Recycled. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/09/11/897692090/how-big-oil-misled-the-public-into-believing-plastic-would-be-recycled

2 Joyce, C. (2019, March 13). Where Will Your Plastic Trash Go Now That China Doesn’t Want It? NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2019/03/13/702501726/where-will-your-plastic-trash-go-now-that-china-doesnt-want-it

3 Mosbergen, D. (2019, March 9). Here’s Why America Is Dumping Its Trash in Poorer Countries. Mother Jones. https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2019/03/heres-why-america-is-dumping-its-trash-in-poorer-countries/

4 UN Comtrade. (2022, October 12). Distribution of scrap plastic exports from the United States in 2021, by destination [Graph]. Statista. Retrieved April 07, 2023. https://www-statista-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/statistics/1228470/plastic-waste-us-exports-destination-shares-by-country/

5 Environmental Protection Agency. (2021, January 23). Total volume of plastic containers and packaging MSW generated in the United States from 1960 to 2018, by product (in 1,000 tons) [Graph]. Statista. Retrieved April 07, 2023. https://www-statista-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/statistics/1229615/us-plastics-container-packaging-waste-generation-by-product/?locale=en

6 Association of Plastic Recyclers. (2022, April 22). Recycling rates of post-consumer plastic bottles sourced in the United States in 2019 and 2020, by material type [Graph]. In Statista. Retrieved April 07, 2023. https://www-statista-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/statistics/623553/plastic-bottle-recycling-rates-in-the-us-by-material-type/?locale=en

7 Depaul, K. (2021, February 2.) What Does It Really Take To Build A New Habit? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/02/what-does-it-really-take-to-build-a-new-habit

8 Marazzi, L., Loiselle, S., Anderson, L.G., Rocliffe, S., & Winton, D.J. (2020). Consumer-based actions to reduce plastic pollution in rivers: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach. PLoS ONE 15(8): e0236410. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236410

9 The Recycling Partnership. (2022, July 28). The Recycling Partnership’s Polypropylene Recycling Coalition Celebrates “Widely Recyclable” Upgrade. https://recyclingpartnership.org/the-recycling-partnerships-polypropylene-recycling-coalition-celebrates-widely-recycled-upgrade/

10 Freeman, J. (2018, July 25). The Incredible Campaign Against Plastic Straws. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-incredible-campaign-against-plastic-straws-1532545186

11 Cohen, G., Pless, J., & Toome, E. (2022, March 16). Can Entrepreneurs Save the Planet? Frank Hawkins Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise (unc.edu). https://kenaninstitute.unc.edu/kenan-insight/can-entrepreneurs-save-the-planet/

12 Sengupta, S. (2020, July 30). 9 Innovations for Recycling and Replacing Plastics. 17 Goals. https://www.17goalsmagazin.de/en/9-innovations-to-up-cycle-plastic-waste

- Keyword(s):

- innovation 188

- stakeholder capitalism 57