Health Disparities Were Devastating BIPOC Communities. Then Came COVID-19.

The factors determining a person’s health go far beyond what happens in the doctor’s office. To be healthy, a person must not only have access to healthcare but also be able to obtain healthy food and have a safe place to work, live and exercise. Community and social support also play an important role.

In one out of five communities in the U.S., people can’t access what they need to be healthy. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this problem and revealed just how much an individual’s health depends on their surrounding community.

During the 2020 Business of Healthcare conference presented virtually by the UNC Center for the Business of Health in November 2020, experts from various parts of the nation’s healthcare system discussed contributors to social inequalities that affect health and examined how innovation and interconnectivity can build a more robust healthcare system. View the full conversation.

Pervasive inequities

Health in the U.S. is strongly affected by the structural racism and discrimination that Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) have experienced for generations. A Georgia State University study found that African American youth who experienced racial discrimination were more likely to have elevated depressive symptoms in adolescence and early adulthood.1 This is just one example of how discrimination can directly affect health and potentially influence the accelerated aging and racial health disparities, such as high rates of Type 2 diabetes and heart disease, seen in Black populations.

The relationship between racism and health has become increasingly stark during the pandemic as BIPOC communities are not only experiencing higher rates of COVID-19 infection but also higher mortality rates. Although the factors behind these trends are still being studied, it is likely that housing problems, exposure to pollution and other issues that have long plagued these communities have put them at higher risk of chronic conditions that increase susceptibility to COVID-19.

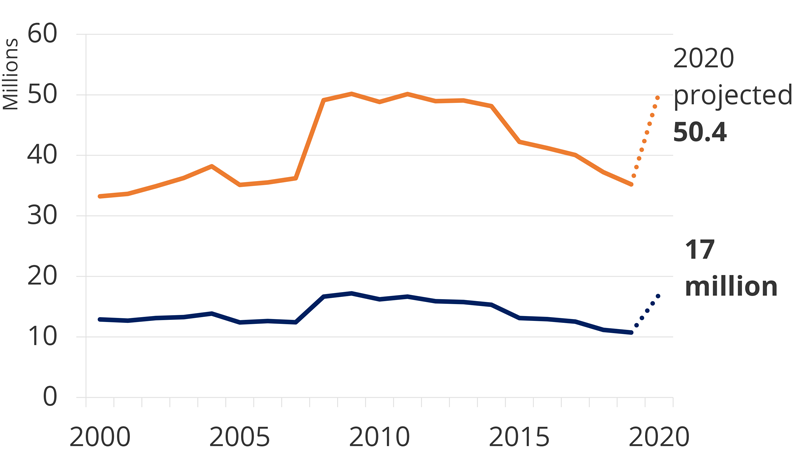

Food is another upstream social factor that strongly influences health and disparities. Studies show that children experiencing food insecurity are least 1.4 times more likely to have asthma than food-secure children, while seniors with food insecurity seem to age faster, exhibiting limitations in daily activities comparable to those of food-secure seniors 14 years older.2 Almost 50 million people in the U.S. are food insecure, a number that has only risen as COVID-19 has interrupted supply chains and left many individuals without jobs. Even areas that are known for producing the country’s food, such as the Midwest, are experiencing staggering levels of food insecurity, with likely health impacts to be seen for years to come.3

Trust, privacy and policy

What will it take to improve health for everyone — including those who struggle with socioeconomic challenges? To even begin, we need a coherent and standardized framework for understanding and addressing the structural issues involved in health on an individual and community level.

Addressing lack of trust in healthcare is key. Susan DeVore, CEO of Premier, says that when people experience discrimination by clinicians or don’t receive culturally sensitive care, winning back their trust becomes critical to improving their health. This is particularly relevant to the rollout of COVID-19 vaccination plans. Successful vaccination efforts will be those that understand where the community has placed its trust, and work through those institutions to reach individuals. This can often be accomplished by forming positive relationships with community leaders who can build trust by example.

Data has a role to play in addressing health disparities, but it must be used responsibly. Ruth Krystopolski, senior vice president for population health at Atrium Health, notes that the pandemic has highlighted the barriers that outdated privacy laws pose for researchers seeking data to understand public health problems and inform solutions. It is also crucial to measure and monitor interventions to make sure that they actually produce improvements. However, when data is being used to expose health inequities, it is important to avoid inadvertently feeding stereotypes or bias. A 2019 study showed that an algorithm used to predict health risk (and influence treatment for millions of people across the U.S.) exhibited significant racial bias.4

John Lumpkin, president of the BCBSNC Foundation, emphasized that the communities most at risk are the ones that have been adversely affected by public and private policies reflecting decades of disinvestment. Funding formulas and other policies need to recognize these historical disparities and enable a more equitable distribution of resources. Lumpkin also pointed out that creating more equitable and local food systems would bring benefits on several levels. Not only is a local food system better for health, because it provides recipients with fresher products that aren’t overprocessed, but it also creates local jobs and enables local farmers, including farmers of color, to get their products to market quicker.

Incentivizing impact

Finding better ways to address social determinants of health will require the many players in the U.S. healthcare system to work together to develop innovative new solutions. It is no longer sufficient to treat a patient’s diabetes with a prescription for insulin. Clinicians also need to find out where that patient can purchase healthy food, whether she has access to a place to exercise and if she has appropriate transportation to get to appointments and the pharmacy. All of these factors will determine how well the patient manages her diabetes.

A move away from fee-for-service toward value-based structures that incentivize and reward quality care could help. Such a shift would not only encourage cooperation among clinicians, who are now competitors, but also create an imperative to care for the sickest and less advantaged, many of whom will require costly services later if conditions aren’t managed.

DeVore points out that although incentives have been moving toward a value-based system for some time, it isn’t happening as quickly as it could. One reason for the slow progress is that there are relatively few ways to experiment with new solutions or to bring experimental programs up to the scale needed for practical application. Problems accessing electronic health records and claims data due to privacy laws are also a roadblock.

In addition to changing incentives, Krystopolski points to a need for solutions to regulatory, legal and compliance challenges in healthcare. For example, if a healthcare system provides transportation for a patient to get to an appointment without getting a waiver or consent form, they could potentially be accused of inducement of individuals. Removing some of this red tape could make it easier for healthcare systems to provide the full range of services their patients need to be healthy.

Finding the right balance

There is an urgent need to go beyond fixing healthcare and focus on all the factors that contribute to health. DeVore says that the public sector can be part of the solution by setting rules and guidelines for work being done to address social determinants of health. Government should also help coordinate solutions to minimize overlap and prevent unintended outcomes, while still allowing the private sector to innovate and collaborate to solve healthcare problems. Krystopolski notes that mental health is a key area in which the government could contribute by providing additional funding and resources. The fact that healthcare systems cannot adequately address the behavioral health needs of their patients is contributing to a great deal of extra healthcare spending.

Public-private partnerships can also play a role in addressing attributes of communities that make it hard to maintain health. For example, they can work to eliminate food deserts, improve transportation and create jobs in places where these are needed. Enrique Conterno, CEO of FibroGen, Inc., says that when private and public enterprises have incentives that align around outcomes, rather than activity, it can bring about faster advances with good outcomes. As an example, he points to the public-private partnerships that brought many different groups together to develop COVID-19 vaccines and treatments in record time.

Finally, expanding access to health insurance — such as through the Affordable Care Act or Medicaid expansion — could go a long way toward addressing nonclinical determinants of health. DeVore points out that Medicaid has been expanding for about a decade, and there’s ample research to show that health outcomes improve when people have access to affordable insurance. As an example, Lumpkin notes that in North Carolina the lack of Medicaid expansion has created a coverage gap that leaves the working poor often choosing between medical bills, rent, transportation to work and food. Medicaid expansion would not only relieve some of that financial burden but also help address social needs, creating an environment where healthy choices and healthy outcomes are more likely.

DeVore says that with the current closely divided federal government, many of the sweeping initiatives meant to expand access to insurance, such as Medicare for All or a public option, likely won’t be achievable. However, other approaches such as improving incentives, encouraging collaboration and partnerships, and making it easier to share data are all feasible and have the potential to lower healthcare costs and improve the health of the American people.

1 Carter, S.E. et al. (2019) The effect of early discrimination on accelerated aging among African Americans. Health Psychology 38(11), 1010-1013.

2 Gundersen, C. and Ziliak, J. (2015) Food Insecurity and Health. Health Affairs 34(11), 1830-1839.

3 Saraiva, C., Gonzalez, C., and Forte, P. (2020) Workers Keeping Americans Fed Are Going Hungry in the Heartland. Bloomberg. Saraiva, C., Gonzalez, C., and Forte, P. (2020) Workers Keeping Americans Fed Are Going Hungry in the Heartland. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2020-hunger-minnesota-pandemic/?srnd=premium

4 Obermeyer, Z. et al. (2019) Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science 366(6464), 447-453.