Rethinking Economic Distress: Why NC’s County Tiers System Is Due for an Overhaul

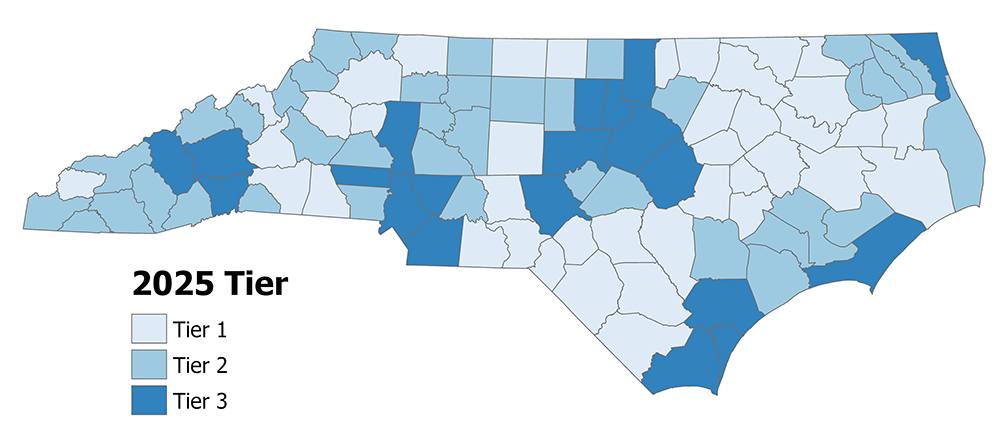

In 1987, North Carolina adopted a relatively straightforward way to direct economic support toward its struggling counties: rank them by distress and offer tax incentives to those at the bottom. The result was the County Tiers System, which grouped all 100 counties into three tiers based on economic indicators such as unemployment rate and median income.

Though the system appears data-driven and objective, stakeholders say it frequently fails to reflect real economic conditions. As one researcher put it, “It’s not completely clear to me what it measures.”

Decades later, that once-simple tool is serving more purposes but delivering fewer results. No longer confined to job creation incentives, the Tiers System is now used to allocate funding and determine eligibility across a wide range of state and nonprofit programs. Yet recent analysis – detailed in An Assessment of the North Carolina County Distress Rankings (Tiers), a report by NCGrowth and the ncIMPACT Initiative, supported by the North Carolina Collaboratory – shows that the system is poorly understood and increasingly misaligned with both economic reality and stakeholder needs. The study highlights an opportunity to rethink how North Carolina identifies economic distress and to design tools that more effectively support the state’s long-term goals.

Where the Tiers System Falls Short

Each year, the North Carolina Department of Commerce assigns every county a distress score based on four factors:

- Average unemployment rate

- Median household income

- Percentage population growth

- Adjusted assessed property value per capita

Counties are then ranked and split into tiers. The 40 “most distressed” counties are Tier 1, the next 40 are Tier 2 and the remaining 20 are Tier 3. Lower tiers receive priority for funding and incentives.

Though the system appears data-driven and objective, stakeholders say it frequently fails to reflect real economic conditions. Over time it has become increasingly misaligned with both its original purpose and current applications. As one researcher put it, “It’s not completely clear to me what it measures.” The report identifies several specific weaknesses in the Tiers System.

- A foundational issue is the system’s reliance on forced categorization. Every year, exactly 40 counties must be placed into Tiers 1 and 2, with the final 20 going to Tier 3, regardless of actual economic conditions. This rigid sorting can group together counties with vastly different levels of need or separate those with nearly identical profiles.

- In practice, small differences in county data can produce big shifts in rank. A county may move up or down a tier simply because of changes in another county’s rank. This volatility introduces uncertainty for local governments and undermines long-term planning.

- Meaningful economic differences might be flattened. A county with just $4 more in per capita income can be grouped with one that has a $6,000 advantage, creating the impression that they are equally well off.

- County-level averages also overlook internal disparities. In many urban counties, high overall income levels mask areas of concentrated poverty, leaving neighborhoods in real need overlooked. Yet the tier designation treats entire counties as if they share the same conditions, with little ability to account for whom within those counties is struggling.

- The Tiers System is also used far beyond its intended scope. Despite multiple attempts at reform, it continues to be used in decisions about education, health care, infrastructure and even environmental and veterinary programs. Over time, it has become shorthand for need – one that influences program eligibility, required local contributions and funding prioritization, even when its relevance is unclear.

- This widespread use has led to unintended consequences. Counties that show economic improvement can be moved into a higher tier, reducing their access to resources. As a result, local leaders may find themselves publicly celebrating progress while privately worrying about losing critical funding. Conversely, many officials mistakenly believe that being in a lower tier is essential for securing state support, fueling pressure to remain ranked as distressed.

- Perhaps most concerning, the system fails to effectively target where need is greatest. More people live in poverty in Tier 3 counties than in Tier 1 and 2 combined, raising questions about how the model distributes resources. The tiers also do little to reflect how rural isolation, racial inequity and historic patterns of disinvestment shape opportunity across the state.

So What Comes Next?

The report points to several areas for further exploration that could inform a more effective approach to assessing economic distress. These include:

- Identifying all programs that currently rely on the Tiers System.

- Understanding the administrative and political considerations of replacing it.

- Exploring alternative models based on statistical clustering or longitudinal trends.

- Clarifying what a designation system is ultimately meant to achieve: helping places or helping people?

Clarifying the purpose of any future model is essential. If the goal is to lift up the most economically distressed individuals, regardless of where they live, then the current county-level approach falls short. If the aim is to boost rural economies, that too must be made explicit – and paired with a tool that accurately identifies rural disadvantage. The shift toward a more responsive model will require diverse stakeholder input, transparency and political will, but the payoff could be a system that better matches North Carolina’s long-term goals.

Matching Tools to the Goals They Serve

A key recommendation emerging from the report is that no single system should serve every program. Several interviewees suggested that different policy areas may require different tools. For example, some proposed a more flexible, index-based model to track county progress over time relative to the state as a whole. Others raised the possibility of using more localized geographic units, such as census tracts, to better identify pockets of need that county-level data may obscure. A few also expressed interest in systems that allow for local nomination or self-identification of distress.

Some states have already moved in this direction, adopting more tailored systems such as targeting based on regional economic clusters, longitudinal performance data or more granular demographic indicators.

Importantly, many pointed out that the current model does not account for how factors like race, rural geography and historic disinvestment shape economic disadvantages. These limitations suggest the need for more tailored approaches, particularly for programs focused on addressing specific population-level disparities.

Conclusion

The Tiers System has persisted in part because it is widely used and already embedded in many state programs. But the report shows that it no longer captures the complexity of economic conditions across the state and is often applied in ways that do not align with actual need.

As North Carolina looks to the future, the findings offer an opportunity to reconsider how economic distress is defined and how resources are targeted. With input from stakeholders across sectors and a careful evaluation of alternatives, the state can move toward a model that is more responsive, equitable and aligned with long-term goals.

For a full discussion of stakeholder insights, methodology and alternative approaches, see the full report, Assessment of the North Carolina County Distress Rankings (Tiers), available in the Research section at ncgrowth.kenaninstitute.unc.edu.