Tackling the Housing Crisis Brewing in America’s Native Communities

Compared with other identity groups, American Indians have some of the worst social and economic outcomes and are more likely to be negatively affected by funding cuts and policy changes. One of the most critical problems facing Native American communities is housing.

American Indians have some of the worst social and economic outcomes and are more likely to be negatively affected by funding cuts and policy changes.

As in many places in the United States, the number of affordable homes in Native American communities is declining, while the units that are available are becoming more expensive. The situation for American Indians is amplified because many of the homes available in their communities are decaying to the point that they must be condemned, further decreasing housing stock. In addition, private developers are not motivated to build in the rural areas where most American Indians live because profitability is limited. If developers do come, they may buy land meant for mobile homes and raise the lot rents for mobile homeowners, a large percentage of which are American Indians in such communities.

How did we get here?

Central to the problem is the fact that the federal government has not substantially invested in affordable housing since the 1970s. Today’s affordable housing structure, mostly instituted through the federal Section 8 housing choice voucher program, is a hybrid public-private model in which people use subsidized vouchers to rent units in privately owned housing developments. The Community Development Block Grant program further decentralizes affordable housing by allowing states to fund projects that meet their specific needs. These models have some economic benefits, but also key flaws.

One pitfall is that today’s affordable housing structure allows developers who build apartments with Section 8 units to institute restrictive policies that effectively shut out those who need these units the most: cost-burdened renters with prior involvement in the justice system. Racism can also hinder the expansion of affordable housing when residents oppose new projects due to concerns over the type of people perceived to live in affordable housing developments. Also, the grant-based funding structure of many affordable housing programs makes it difficult to implement solutions that go beyond the current budget year.

The rural location of many Native American communities brings additional challenges. Rural renters tend to have lower income than those in urban centers; at the same time, they spend a large portion of their budget on transportation because they don’t have access to public transit. Rural communities often rely heavily on mobile homes as affordable housing. Most mobile homeowners do not own the land their unit sits on, have poor legal protections, use high-risk loans to finance their property, and obtain lengthy mortgages, which makes full ownership of their mobile home very difficult.

Spotlight on North Carolina

To dig deeper into the crisis, we examined demographic and economic data and the impacts of relevant policies and programs in North Carolina, home to the largest American Indian population east of the Mississippi River. The state’s American Indians encounter many of the same challenges as those in other parts of the country, with a large contingent living in rural areas and with mobile homes serving as a primary source of affordable housing. According to available data, the state has the third-largest number of mobile home units in the United States.

North Carolina also has some unique factors at work. Tribes located in the state’s Coastal Plain — the Lumbee, Coharie, Waccamaw Siouan, Meherrin and Haliwa-Saponi — are especially vulnerable to flooding and hurricane damage. The city of Lumberton, where many Lumbee live, lost 25 percent of its affordable housing units after hurricanes in 2016 and 2018. The region also has many large pig and chicken farms, which suppress housing prices, deter affordable housing developers and create environmental hazards during floods.

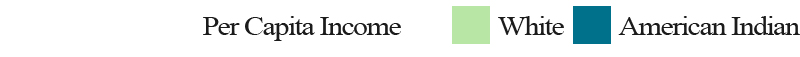

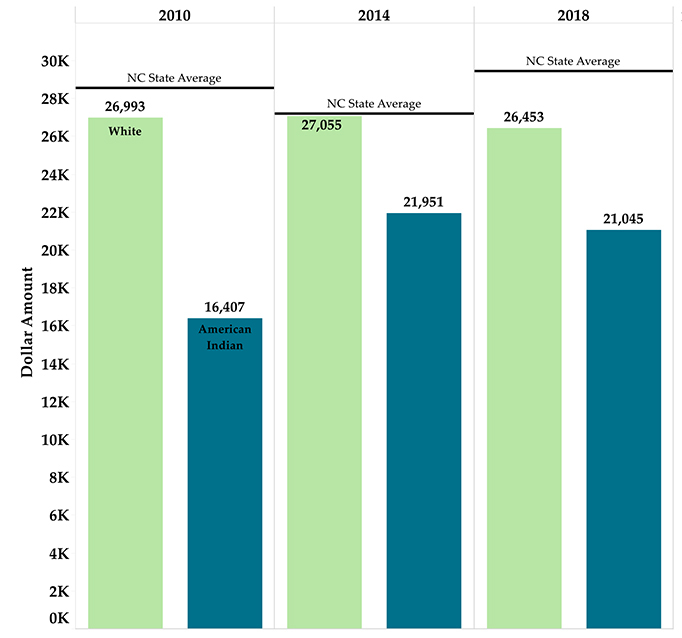

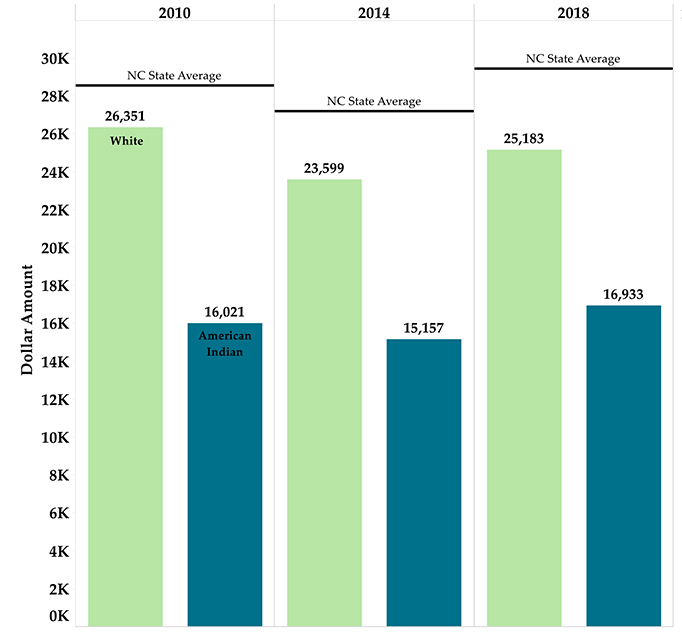

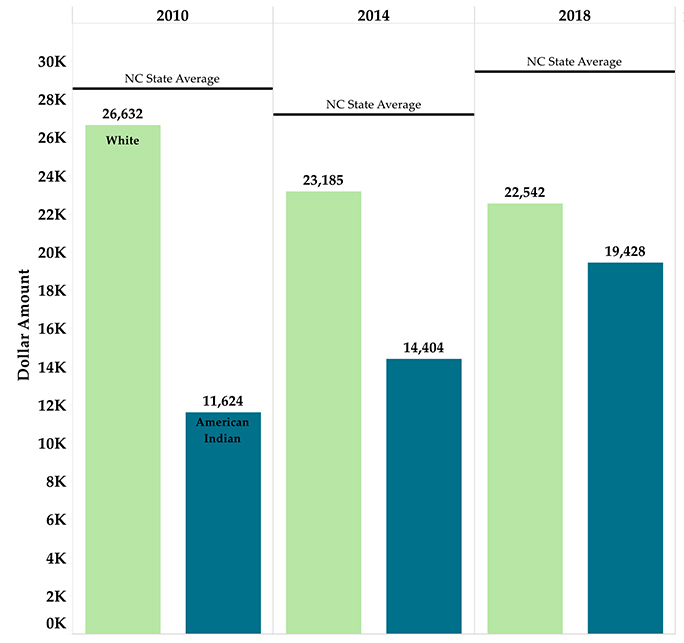

More than half of the state’s American Indians live in Halifax, Robeson, Sampson and Swain counties, the cultural centers for the state’s four largest tribes. Housing and economic data in these counties reveals large disparities between whites and American Indians. Our analysis found that Native communities often face risky and unaffordable housing options, lack the economic resources required for upward mobility and are disconnected from digital resources.

Although these disparities have been evident in each of the counties studied going back at least a decade, there is one community that seems to be narrowing the gap. Compared to other tribes and the state of North Carolina as a whole, the Eastern Band of Cherokee have seen some improvements in local housing and other socioeconomic outcomes. This could be due to the federal funding and programming they receive under their status as the state’s only federally recognized American Indian tribe.

Baby bonds and better homes

We identified several promising options for addressing the housing crisis and improving the broader economic situation in tribal communities. The first is to create “baby bonds” that offer direct payments to individuals. The Minor’s Trust Fund program of the Cherokees sets aside a percentage of yearly profits from the tribe’s Harrah’s Cherokee Casino and Resort and provides funds to registered tribe members at age 18, 21 and 25, along with biannual checks thereafter. Studies show that people who received these payouts had better outcomes in housing, economics and education than those born before these payments were established, as well as compared to non-Indian residents in that area of the state.

Similar programs could serve as a powerful tool to improve the outlook for other marginalized communities. However, tribes that lack federal recognition — and associated benefits such as sovereignty over large plots of land and the ability to run large, money-making establishments like casinos — may have trouble generating the necessary funds. For these tribes, a baby bond program may require backing from a government entity or a financial institution, which could pose significant barriers.

Another option is to weatherize existing mobile homes. High utility costs are one of the main factors that make living in mobile homes difficult to afford; a large-scale effort to refurbish homes with items such as EnergyStar appliances, proper insulation, and low-flow showers and toilets can reduce housing costs, help aging units last longer and provide jobs for those doing the work. Although new units would still be needed eventually, weatherizing could offer an inexpensive first step and buy communities more time to expand affordable housing stock. Policy solutions that make mobile homes both safe and energy efficient are also important, including policies that help protect those in flood zones.

A cooperative model for ownership and operation of mobile home parks could also help address risks such as unexpected rent increases and evictions. Owners in Resident Owned Communities (ROCs) can get assistance from the community for repairs and improvements and help make decisions for the community rather than being at the mercy of landlords. The nonprofit ROC USA assists ROCs, mobile homeowners and landlords with implementing ROCs.

Exploring different types of housing, such as communities of “tiny homes” — fully functioning units that are typically 400 square feet or less — could complement other solutions to help alleviate the housing crisis. The construction costs for tiny homes can be much lower than traditional homes or apartments, though these homes are best suited for 1-2-person households such as young people or elders.

Although such options are promising for temporarily offsetting housing issues affecting American Indians, structural changes to the mechanisms that keep marginalized communities in socioeconomically disadvantaged positions are necessary to solve the issue in the long term. Advocacy efforts should focus on stopping federal, state and local cuts to housing programs and reversing policies that erect barriers to housing access. Philanthropic and private funding can move things forward. One thing is clear: the responsibility for eliminating disparities should not rest solely on the shoulders of those bearing the burden.

All information and original data sources are cited in the full report.