The Land of Opportunity (Zones)

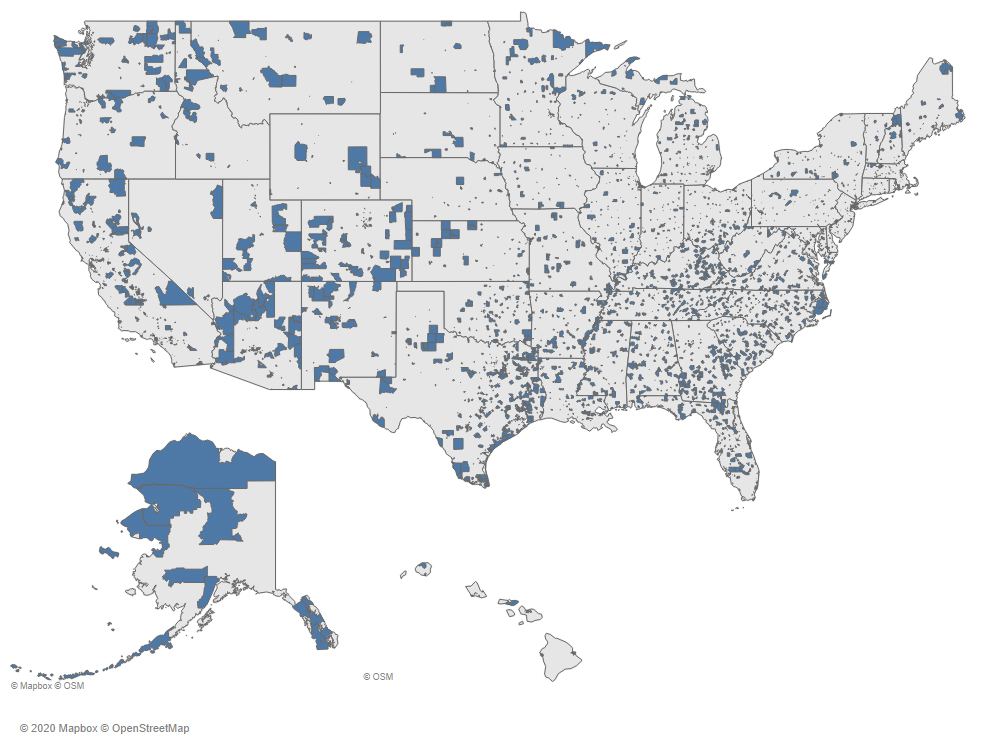

In the hope of bolstering poor communities, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) allowed for the creation of Opportunity Zones (OZs) — specially designated census tracts encompassing low-income neighborhoods meant to stimulate investment through large tax incentives. Responding to these incentives, investors poured money into so-called Opportunity Funds, and Republicans have touted the large influx of capital as evidence that these policies have been wildly successful. Indeed, midway through his 2020 State of the Union Address, U.S. President Donald Trump proclaimed, “Jobs and investments are pouring into 9,000 previously neglected neighborhoods thanks to Opportunity Zones… Wealthy people and companies are pouring money into poor neighborhoods or areas that haven’t seen investment in many decades.”

In a contrasting narrative that several prominent Democratic lawmakers have suggested, this policy is not spurring additional investment, but rather rewarding politically connected investors. These critics maintain that investors with existing projects in poorer neighborhoods have lobbied to have those neighborhoods reclassified as OZs in order to reap large tax benefits.

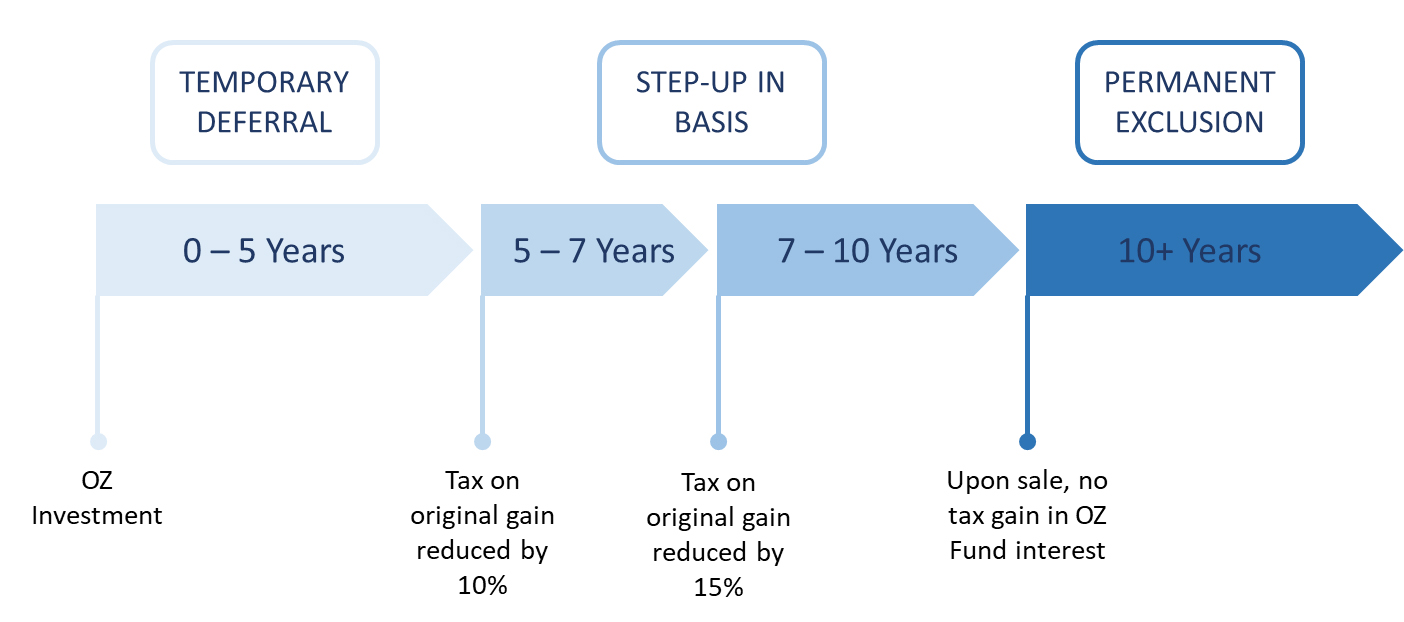

OZs reward investors in three ways. First, investors can defer capital gains on the sale of an asset if those gains are redirected into an OZ investment. Second, if the OZ investment is held long enough, a portion of those deferred gains are excluded (10 percent for holding five years, 15 percent for holding seven years). Finally, if capital invested in an OZ is held 10 years, the entire capital gain is eliminated and investors enjoy an adjustment of basis to the fair market value the day the investment is sold. Given these incentives, understanding whether there is political bias in OZ selection — and if so, how to mitigate that bias — is vital.

Selection of Opportunity Zones

The selection process for OZs began with the U.S. Treasury Department, which identified more than 40,000 eligible tracts. These tracts had to come from low-income communities, which the TCJA defined as areas where the poverty rate was 20 percent or higher (compared with the national average of 15.1 percent), or the median household income was below 80 percent of the local median household income. Alternatively, some of the tracts could also be adjacent to low-income communities — with the goal of spurring economic forces for the nearby low-income communities.

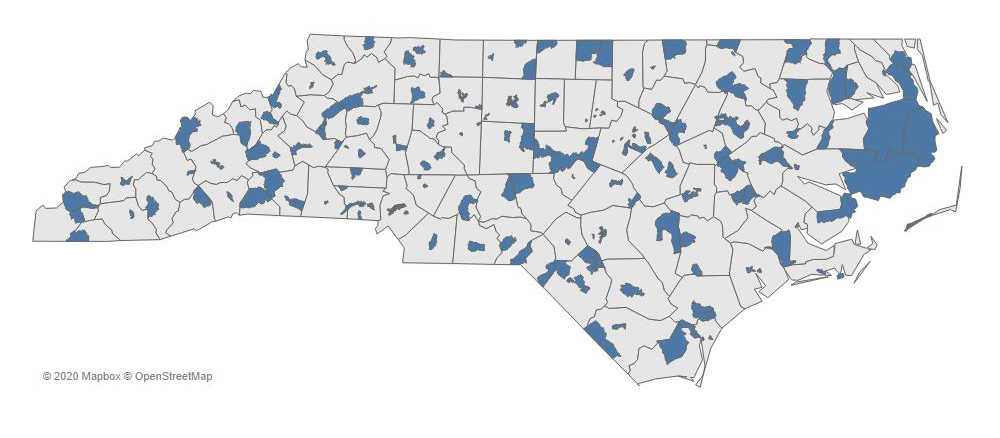

Of the eligible tracts, state governors were allowed to select up to 25 percent of those in their own states to be designated as OZs. This selection by governors introduced a subjective, potentially biased aspect to the process. Because governors, both Republican and Democratic, were allowed to select their state’s OZs, whether they chose tracts dominated by their own political constituency gives us insight into whether the process was biased. UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School Professor Jeff Hoopes, who also serves as UNC Tax Center research director, working with UNC Tax Center Research Fellow Mary Margaret Frank of the University of Virginia and Becky Lester of Stanford University, explored whether the dominant political party of a census tract affects the likelihood of the tract being chosen as an OZ by a governor affiliated with that party. In other words, do Republican governors tend to choose OZs full of Republican constituents, and Democratic governors those dominated by Democrats? The researchers found an increase of 6.8 percent in the likelihood of a tract being selected if it shared political affiliation with the governor.

However, while the evidence suggests political bias does affect OZ selection, this bias may not be due to politicians distributing incentives to their friends. Alternatively, state governors may have better information on the challenges and potential of areas dominated by constituents of their own party than other areas. They simply may be making their selections because their greater information leads to more confidence that constituents would benefit from being in an OZ.

The research team then looked at the different processes governors used to choose between potential OZs. The three primary tools governors used were professional engagement, public comment and applications. They found that professional engagement — the hiring of public advisors to analyze and make recommendations — and, to a lesser extent, public comments, mitigated the effects of political bias in the results.

Why even use place-based incentives?

OZs are an example of placed-based tax incentives, which stand in contrast to most tax incentives available to all filers. Place-based policies target specific geographical areas, with a goal of providing investment, economic growth, jobs, higher incomes, etc. Many favor these incentives over traditional incentives, and some researchers call for an increase in their use. Historically, economic disparity between geographic regions in the U.S. has been the norm, but the dynamics of our economy have led toward a steady convergence of poorer and wealthier areas in terms of economic success. Until the 21st century, poorer Americans would migrate to high-income regions in search of opportunity, and investment was attracted to the lower wages in poorer areas. In recent years, however, these trends have ended or reversed. Americans, especially young adults, are migrating at the lowest rates since the U.S. Census Bureau started tracking such movement in 1947. Important funding for creating new jobs, such as venture capital funding, is becoming more concentrated as startups prefer the skill base of expensive areas such as Silicon Valley over low-income areas without a highly skilled workforce.

Proponents of OZs believe they can help address regional declines and lack of investment. However, the effectiveness of such a policy depends on efficient choice of OZs to maximize gains to the disadvantaged communities best positioned to capture them.

Discussion

While we see some evidence of bias in the OZ decision-making process by governors, it appears that proper processes can mitigate that bias. Also of note is that other factors played a major role in selection. Although the low-income communities selected by the U.S. Treasury Department required only a 20 percent poverty rate or a median household income rate of 80 percent of local median income, the research team found that poorer tracts were much more likely to be selected, even from among the already poor tracts. An increase of one standard deviation in the poverty rate corresponded to a 7.5 percentage point increased chance of being selected. A decrease of one standard deviation in median income increased the chance of being selected by 5.6 percentage points. Both of these factors dwarf the 1.6 percentage point bonus from party affiliation, indicating that at least some of OZ selection was based on the poverty of the area rather than its political leanings.

We are still too early in the process to determine whether OZs have been generally successful, but recent research has provided insights into effective targeting with place-based incentive policy. The OZ project benefitted from a two-step process in which potential OZs were objectively identified from a federal source that didn’t make subsequent selection decisions. This separation of powers allows for greater objectivity in selection. Analysis done by Hoopes, Frank, and Lester expands on this work, finding evidence that the engagement of outside professionals may help mitigate any political bias.

1 “Full Transcript of President Trump’s State of The Union Address” (2020)

2 Summers (2018)

3 Sala-I-Martin (1991)

4 Berry & Glaeser (2005)

5 Tavernise (2019)

6 Kenan Institute for Private Enterprise (2020)