In this week’s commentary, we’ll discuss the robustness of the improved health statistics, what the president’s executive orders mean for the economy and the first estimates from our undetected cases model. We do this with an eye toward what could be impending deterioration on both the pandemic and economic front.

The healthcare data mostly show improvement over last week, both nationally and in North Carolina. The number of new cases, hospitalizations, positivity rates and infection transmission rates (“R- naught ”) all declined. While modest, these sustained declines over the last two weeks indicate that the recent surge of infections might be reversing. On the other hand, increasing death rates suggest that far too many people are still paying the ultimate price for the carelessness of those who have not taken the pandemic’s risks seriously. And healthcare utilization rates (our primary variable of concern from an economic policy perspective) held steady at acceptable levels. In North Carolina, the rate has remained in the mid-70 percent range for almost two months now, despite the increase in cases and hospitalizations during the same period.

On the economic front, we see a continued plateauing of consumer spending that is well below pre-pandemic levels. Spending rates, both nationally and in North Carolina, are essentially unchanged since mid-June across almost all the major industry sectors we’ve identified as most sensitive to the pandemic (restaurants, apparel, transportation, etc.). In North Carolina, entertainment spending spiked during the last week of July, but we’re unsure if this is anything more than a statistical blip. Small business activity in the state has stalled, but remains ahead of national activity. Certainly, the best news on the state economic front comes from both the ongoing decline in the insured unemployment rate, which ticked down to 6.4 percent at the end of July, and the continuing separation from the national rate, which remains near 11 percent. We do not yet know the full employment statistics for North Carolina for July; however, the national numbers continued to improve, so we’re optimistic that North Carolina will follow suit. Overall, North Carolina continues to rank near the top of all states in labor market recovery.

But is this the calm before the storm? On the healthcare front, nonessential activity continues to expand, both nationally and in North Carolina. Most recently, many colleges (including those within the University of North Carolina system) have begun returning to in-person classes. Some K-12 schools are resuming classes this month. More people are returning to normal work locations. A resurgence of cases as a result of these activities could lead to further policy restrictions, but just as importantly, to an increase in consumer and worker anxiety that depresses economic growth. Our Consumer Consternation Index has remained nearly unchanged on both the state and national level over the last month, and actually ticked up slightly in our most recent reading. Given how closely the index tracks (and generally leads) broader economic conditions, the uncertainty on the healthcare front for August activity is a concern.

As of this writing, we haven’t seen a compromise in Washington on further economic stimulus. Instead, the president has moved unilaterally with executive orders to extend (at a lower level) federal supplements to unemployment benefits, to suspend payroll taxes for some wage earners and some debt-payment relief and to provide a moratorium on some evictions. It’s a surprising gamble by both sides. While the precise impact of the executive orders remains fuzzy, it does appear that they will drive meaningful benefits for some households in the near term. However, our view is that a compromise package is needed, because many problems can’t be effectively solved by executive orders. Perhaps the two most pressing issues are continued support for small businesses and broader relief to mortgage, rent and student loan payers. The benefits outlined in the president’s executive orders are not only less generous than those proposed by the Democrats (which we believe were excessive in some dimensions) but importantly, are below levels received by beneficiaries through July. Consequently, given that many households and businesses will be worse off now, there’s a significant risk not just to those directly affected but also to the economy more broadly. In fact, it’s likely that the declines we’ve been seeing in unemployment during the last three months could reverse in August. This would further adversely affect the already precarious situation facing state government budgets. We support a return by the U.S. Congress to negotiations around extending the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) for small companies, providing some relief to states who otherwise will be forced to contract spending soon (including on essential services) and having a more deliberate (but reasonable) unemployment and direct stimulus payment program.

We conclude with a summary of work we’ve been doing to estimate the number of undetected cases. One of the challenges facing policymakers, business leaders and the general public in understanding the spread of COVID-19 is the fact that many cases go undetected because of testing shortages or infected individuals not seeking testing (e.g., asymptomatic individuals who may not even consider the need for a test). Having an accurate estimate of undetected infections could help planners make decisions about testing policy and economic openness, let business leaders better understand risks to their workers and customers and inform economic projections. The state of North Carolina provides an interesting case study in infection modeling because the number of positive tests has grown steadily faster than the number of hospitalizations. Likewise, hospitalizations in the state have grown more quickly than deaths attributed to COVID-19. A very simple way to understand the disconnect between deaths and reported new cases is to estimate the total number of cases statewide using lagged data on the number of deaths and recent estimates for infection fatality rates that we provide in our COVID-19 statisticsdashboard. The graph shows that these “death-implied” estimates in North Carolina rose rapidly in March and April, then leveled off. This is obviously at odds with the number of new positive tests, which was quite low in March and April and has only recently approached the number of death-implied cases.

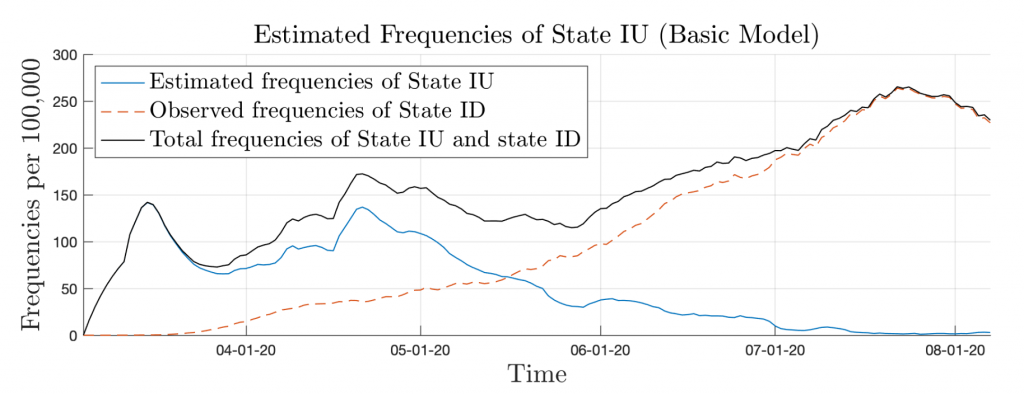

Of course, much better models have been proposed for estimating the number of undetected infections. In our analysis (full report available), we examine a specific model and apply it to data in North Carolina. The model provides estimates of undetected infections (IU) that are plausible, and fits observed levels of positive cases (ID), hospitalizations and deaths very well. We find that the estimated level of undetected cases grew rapidly in early March (see figure below). Estimated undetected cases tapered off in mid-March, grew in early April, and peaked again in mid-April. Since late April, estimated undetected cases have declined substantially, but according to our estimates it was not until mid-May that the number of detected cases exceeded the number of undetected cases. Over this period, the total number of estimated cases stayed fairly constant (100-150 per 100,000). Our results suggest that the substantial increase in testing capacity over the last few months in North Carolina has been successful in identifying a higher percentage of infections. However, it also suggests that much of the recent increase in the number of positive tests represents actual new cases, as opposed to being a consequence of more testing. One concern about our analysis is that we are not able to condition on the age of those with detected cases or who are hospitalized, and consequently, we may underestimate undetected cases if the average age of those infected is declining. Our estimates could also underestimate cases if the quality of care has improved over time and reduced hospitalization and death rates in a way the model does not capture.

Calm before the Storm?