On May 3, the Federal Reserve announced it would raise interest rates by a quarter of a percentage point. The hike marks its 10th consecutive increase, the sum total of which has taken the federal funds rate – the overnight rate charged between banks – from 0.125% a little over a year ago to 5.125% today. This is the most aggressive hiking cycle since the early 1980s. Back in March, I outlined why I expected these rate hikes were eventually going to cause something to break. The recent collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic – as well as the takeover of Credit Suisse – indicates this has indeed come to pass. Even if the Fed is done hiking rates (as it hinted it might be), and even if it cuts them quickly (as some market participants forecast), we will be feeling the negative economic consequences for a while. I believe that there are three potential outcomes resulting from these events, which I outline below.

Three Possible Economic Outcomes: The Bad, the Good, and the Ugly

The first and most likely outcome contains some economic discomfort but avoids a total collapse. In this scenario, there are more hiccups, but the financial system remains generally sound – albeit with meaningfully tighter financial conditions, such as higher interest rates and less credit creation. This will cause a recession, which I still expect will be relatively mild. The strength of the labor market and the health of U.S. balance sheets (low levels of debt and high levels of savings) will mitigate some of the pain resulting from challenging credit conditions. Moreover, better risk management and regulatory systems put in place after the 2008-09 global financial crisis, as well as policy responses learned from that time (such as the quick extension of deposit insurance and takeovers by stronger banks), should limit the contagion from current hiccups. However, the Fed’s mistakes with Silicon Valley Bank suggest a small but healthy dose of concern is warranted.

The most benign outcome is a “soft but bumpy landing” in which the economy manages to avoid a recession through the strength of the labor market. Thus far, there has been little evidence of a meaningful labor slowdown; while mild layoffs have occurred in recent months, they appear to be restricted to specific sectors. Strong hiring would in turn bolster consumer spending and limit the pain from tighter credit conditions. The Fed managed to pull this off in 1994-95, when a series of aggressive rate hikes led to some painful but contained events in the financial system (Orange County, California, went bankrupt and Mexico came close). The U.S. economy slowed but didn’t contract.

The final alternative – which is still fairly unlikely to occur – is a broad financial crisis. If the financial system were to seize up, it would likely lead to a deep recession, as credit would be meaningfully harder to obtain for all but the safest borrowers. The Great Recession resulting from the global financial crisis was the deepest and longest-lasting downturn since the Great Depression and caused a very long painful tail (the COVID-19 pandemic caused a deeper recession, though the economy came roaring back much more quickly than after the Great Recession). I remain cautiously optimistic; as my colleague Greg Brown has illustrated, the banking problems to date are more endemic than systemic because of the guardrails described above. Unfortunately, the crisis outcome becomes more likely each time depositors flee and market participants train their eyes on the next wobbly bank. Healthy assets can become marked down enough that liquidity issues bleed into insolvency, feeding a vicious cycle. Clearly, this would be the “ugly” of our three possibilities.

What Should We Be Keeping an Eye On?

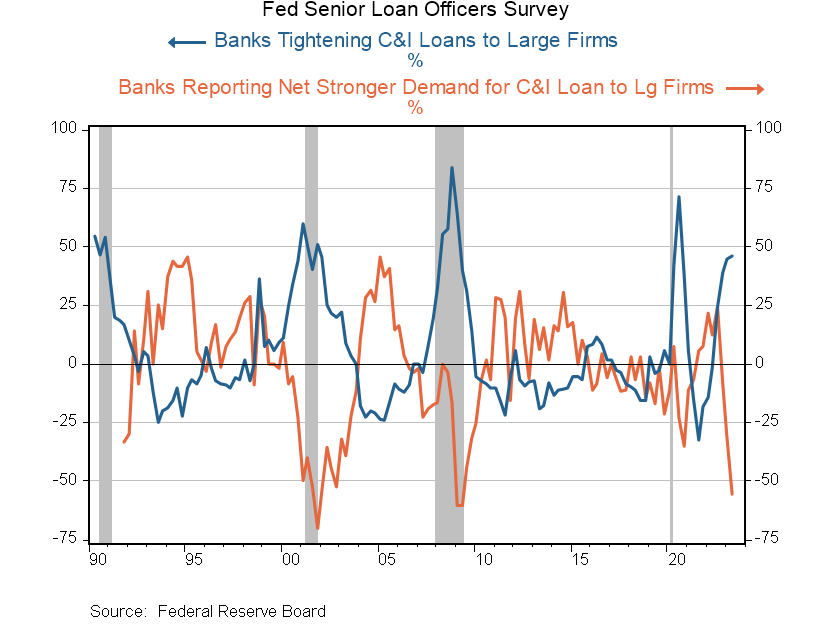

Under the base case of tighter financial conditions and a mild recession (the first scenario outlined above), the interest rates paid by households and business will rise. Subsequently, banks and financial markets will be less forthcoming with credit. These factors will weigh on businesses’ ability to invest and expand – and, in some cases, will lead to shutdowns. Meanwhile, fewer households will be able to borrow money to buy a car or a home. Job losses will likely ensue, leading to further cutbacks in spending exacerbating the slowdown. The beginning of this relatively slow-moving process is already apparent in the data. Even before SVB, banks had been tightening lending standards for both commercial and industrial (C&I) and business loans to near-recessionary levels, as evidenced by the Fed’s Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey (SLOOS). This quarterly survey asks banks about their willingness to lend to businesses and households, the risk premium they are charging customers, and the demand for those funds.

The most recent SLOOS release (published on May 8th) suggests additional tightening has occurred since SVB’s collapse. The blue line in Figure 1 below illustrates this trend for loans to large businesses; small firms showed a similar rise. This survey included a special question about the outlook for the remainder of 2023; banks’ responses indicated a general expectation of tighter standards across all loan categories. At the same time, the interest rate charged by banks (not shown in the graph) increased substantially, resulting in a marked drop in the willingness of businesses to borrow (the orange line is the net of stronger minus weaker demand). Not surprisingly, demand lags behind changes in lending standards and interest rates by a quarter or two (note the lag between the peaks in the blue line and the troughs in the orange line). To summarize: even without SVB, the data was suggesting a weakening of demand to recessionary levels, denoted by the gray bars in the figure, and it has gotten worse since then.

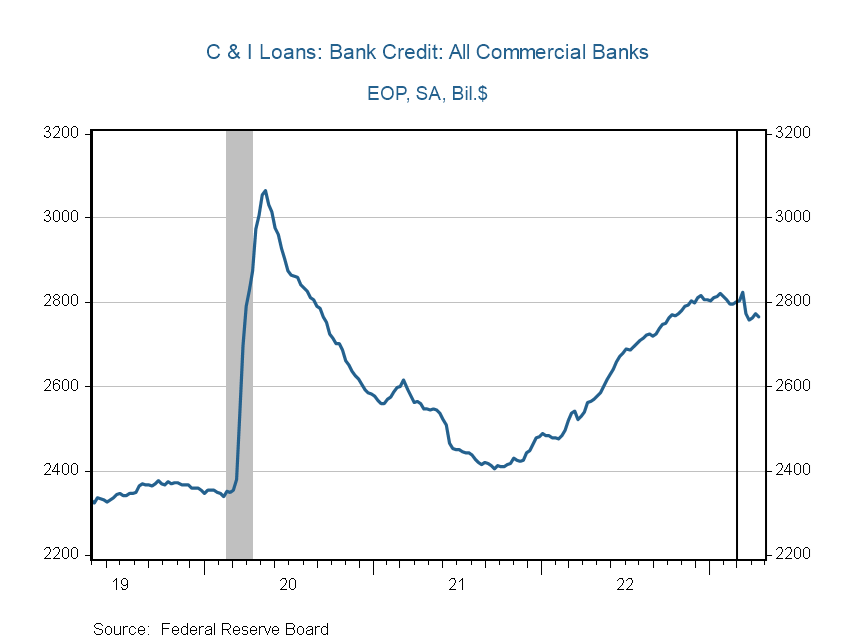

Higher frequency data also suggests that the pain inflicted by recent wobbles in the banking system has translated into an actual contraction in the amount of credit available to businesses (the blue line in Figure 2 below; the black vertical line in the figures below denotes March 1, 2023). This data is released weekly, so we can follow it in real time – and we will be watching it closely. If this trend continues, it is a likely sign of recessionary conditions (the jump in lending in early 2020 and subsequent falloff is an exception because of Paycheck Protection Program loans).

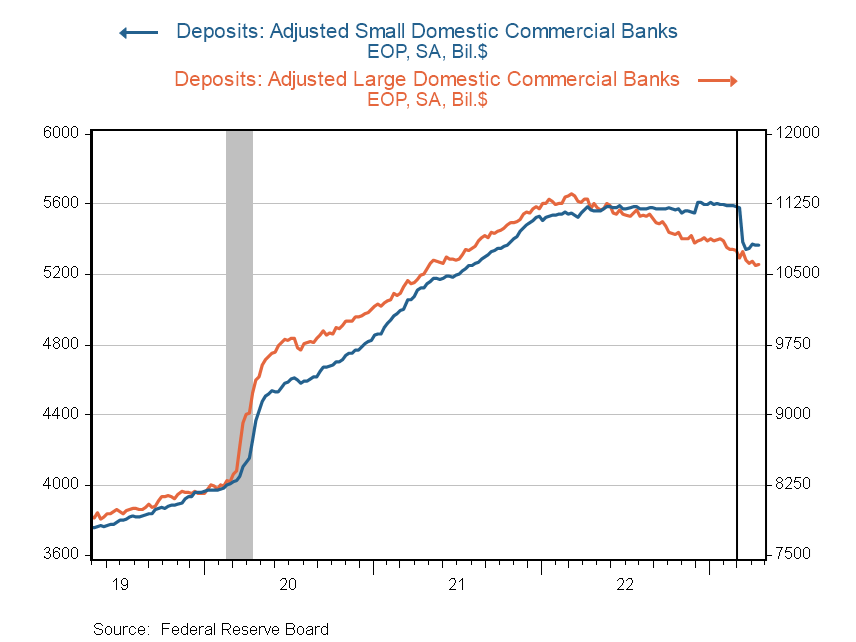

Moreover, the drop in deposits for smaller banks (the blue line in Figure 3 below), suggests that further credit contraction is likely, especially to small- and medium-size businesses (SMEs) and startups. SMEs and startup firms depend more on the relationship-style banking of smaller financial institutions and are unlikely to be able to access credit from financial markets.

Startups are also a significant source of job creation in the economy, well beyond the tech community served by SVB (note that the orange line denoting large banks encompasses the largest 25 banks, which include SVB and First Republic). And, while credit conditions may be the driver, the key outcome is job creation. Current demographic trends suggest roughly 100,000 jobs should be created per month. While this would seem like a significant slowdown from recent readings, it’s actually a sustainable level of job formation, and would be in line with solid economic growth. Until we consistently dip below that level, we won’t be in true recessionary conditions – which is why we think this is a slow burn.

The (Hopefully) Slow Burn of Tightening Financial Conditions