Monopoly Money: Tech and the Changing Geography of Wealth

Executive Summary

With the election cycle well underway, the deep political divisions cutting across the United States are on full display. These divisions largely reflect the nation’s growing economic inequality driven by the changing geographic distribution of wealth that has taken place over the past few decades. With much of the wealth now concentrated in technology and financial clusters such as San Francisco, Seattle, Boston and New York, manufacturing strongholds mostly located in the nation’s heartland have been left behind. Emerging research from Maryann Feldman of the Kenan Institute shows that technology and finance firms have contributed to regional income disparities across America. Three trends are driving this disparity:

- Many top technology companies exhibit a winner-take-all dynamic that creates monopoly power, which in turn makes certain locations invincible by amplifying the benefits companies gain by clustering together geographically.

- These monopolies inhibit local economic development in other places by imposing what can be considered a “tax” on economic activity, while also restricting dissemination and customization of technology.

- The financial sector feeds this dynamic by favoring geographically concentrated big-tech monopolies at the expense of other places and industries.

The rise of technology monopolies

In 1980, the highest concentration of well-paid workers was in Gary, Indiana, followed by Detroit, Michigan, and Washington, D.C. In 2016, Washington, D.C., held the top spot, followed by San Francisco-San Jose, New York and Boston. From 1980 to 2016, these three metropolitan areas, along with secondary hubs in banking and technology, saw the largest increases in the share of workers earning incomes exceeding the 80th percentile nationally, while income in most of the industrial heartland declined.

Emerging research from Maryann Feldman of the Kenan Institute shows that technology and finance firms have contributed to regional income disparities across America.

Today, an outsized proportion of high-paying jobs is concentrated in places where firms have achieved monopoly status, defined as increased market power and the ability to command prices that far exceed the cost of providing a service or good. Consider, for example, Apple, Google and Facebook in Silicon Valley; Microsoft and Amazon in Seattle; and Qualcomm in San Diego.

Feldman and her co-authors attribute the increasing prevalence of monopolies to three factors:

(1) The platform nature of digital technology: Digital technologies benefit from situations in which a growing number of users increases the product’s value to the consumer and/or decreases the costs to the producer (Evans 2003; Gawer 2010; Rochet and Tirole 2006). Digital platform monopolies make their money by controlling access to previously open networks. This affects not only consumers of digital services, but also potential producers of such services.

(2) Extended IP rights: Like digital platforms, firms based on IP rights such as patented software, algorithms, genetic codes and business models have grown, in terms of both their market power and their geographic concentration. For these firms, clustering near other IP-based firms helps lower marginal costs and facilitate the global reach of the monopoly.

(3) Loss of regulatory oversight: The growth of monopoly power occurred under the reinterpretation of anti-trust law pioneered by Robert Bork in 1967. Previously, monopoly power was assessed based on trade restraint; Bork’s interpretation required evidence of harm to consumers. As the Bork interpretation gained popularity in the 1990s, the number of antitrust cases pursued by the Federal Trade Commission dried up, allowing more monopolies to grow unchecked. In addition, because tech monopolies are valuable industries to their home bases, government has limited motivation to regulate them (Iammarino 2018).

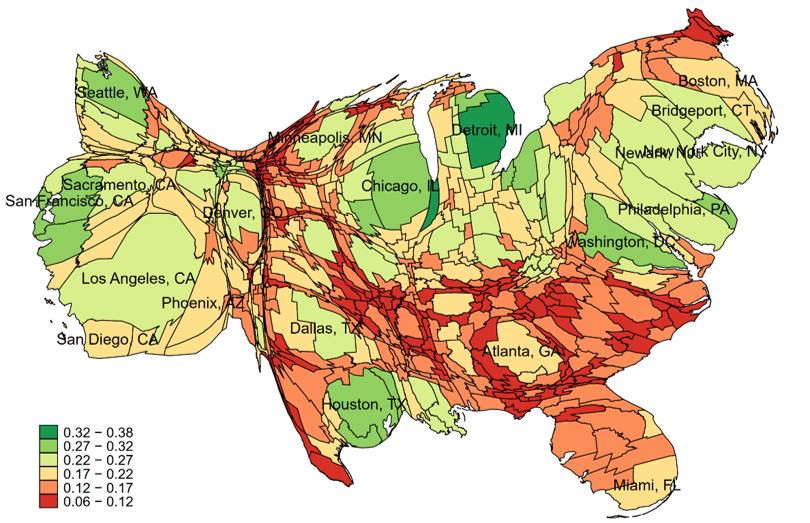

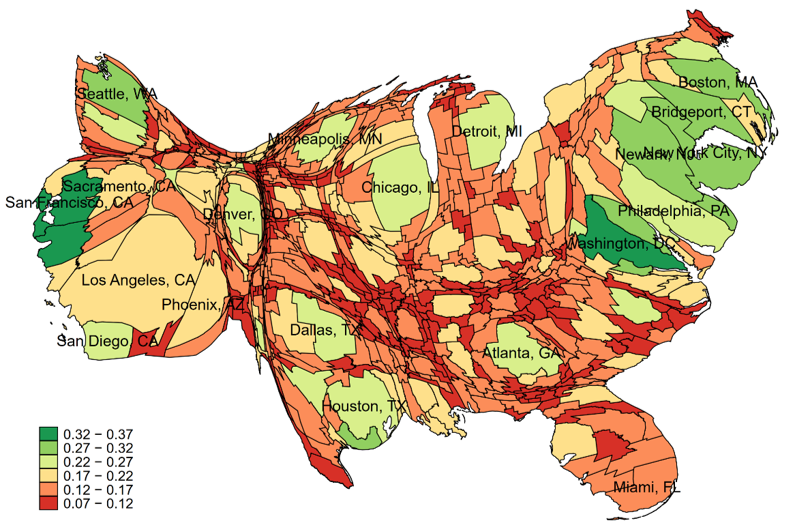

By commuting zone (CZ); areas scaled by population

Concentrated benefits, widespread costs

Companies tend to cluster near other companies that are in related industries, to benefit from proximity to a pool of skilled labor, knowledge spillovers and access to specialized suppliers and customers. While this clustering tendency has been observed for more than a century, monopolies can amplify the effect. In the winner-takes-all world of digital platform monopolies, the value of access to a highly talented workforce and better market intelligence can make the difference between market dominance and irrelevance (Rosen 1981; Sattinger 1979). As a result, such firms derive a great deal of value from proximity to skilled labor and knowledge spillovers, making geographic concentration critical.

The geographic concentration of tech monopolies has many economic implications for communities. Areas with technology clusters have experienced rocketing real estate costs, rising homelessness and transportation problems. On the other hand, places lacking tech monopolies have been not just left behind, but held back. Today’s technology monopolies collect revenues that effectively are a tax on almost all business activities in most parts of the world. For example, intermediaries like Airbnb, Trip Advisor, Booking.com, Expedia (Microsoft) and Uber all take significant slices of revenue from many thousands of globally dispersed small businesses. This situation redistributes wealth from around the world to the shareholders and employees of the platform companies found in a few privileged places.

Finance further feeds monopolies

The financial sector plays an important role in the geography of wealth because it facilitates the movement of capital away from firms with lower returns, which tend to operate in more competitive markets, to firms with monopoly power or monopoly prospects. In effect, this means finance flows to places with monopolies at the expense of those without. This situation has resulted from a shift in which companies have become significantly more dependent on financing. From the 1970s until the year 2000, the typical medium or large American firm was largely self-financing, paying some of its cash flow out to shareholders and using a greater portion for capital expenditure. Since 2000, many firms have paid substantially more of their cash to shareholders or to acquire other firms, with average payouts approximately equaling capital expenditure – resulting in companies relying more heavily on financing.

In a competitive market, increased dependence on financing can indicate increased efficiency of financial markets because capital is moved from less productive uses to more productive ones (Rajan and Zingales 1998). However, the same does not hold true in a market with monopoly power. If higher returns are gained by investing in monopolies, commercial banks are incentivized to strip assets from perfectly viable firms to finance monopolies. When monopolies are found in clusters, this dynamic increases the inflow of capital to monopoly firms and the places in which they invest (Myrdal 1957), inhibiting opportunities for growth or economic revival elsewhere. This dynamic is further intensified by the growing industrial and geographical concentration of commercial banking.