Black Economic Futures

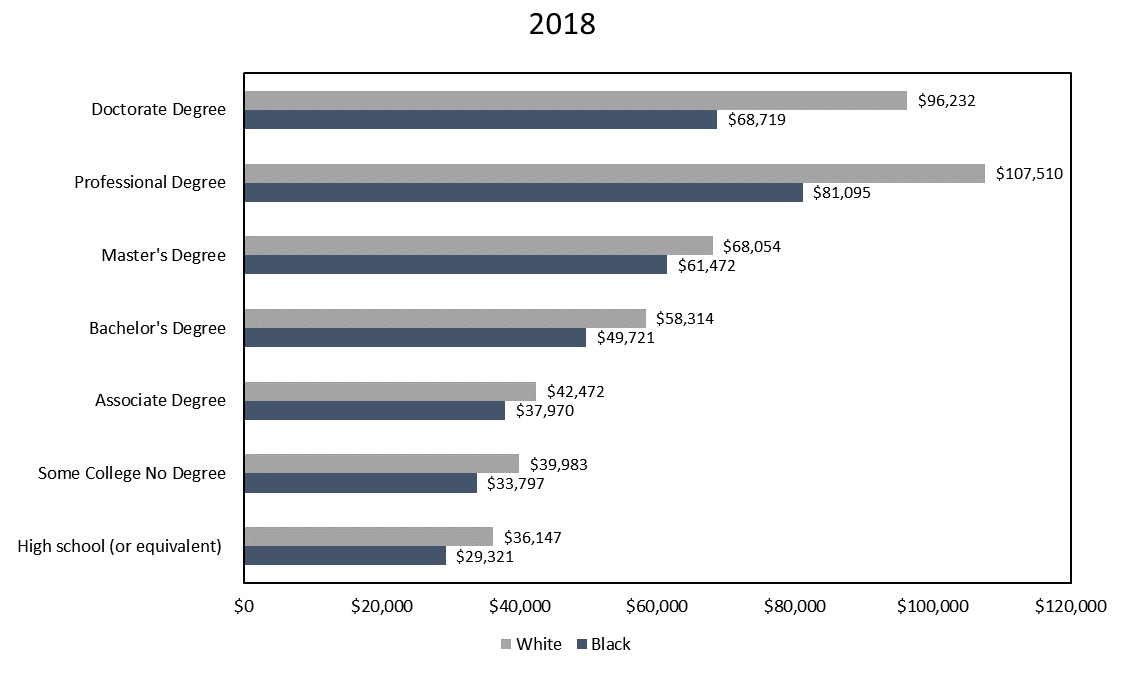

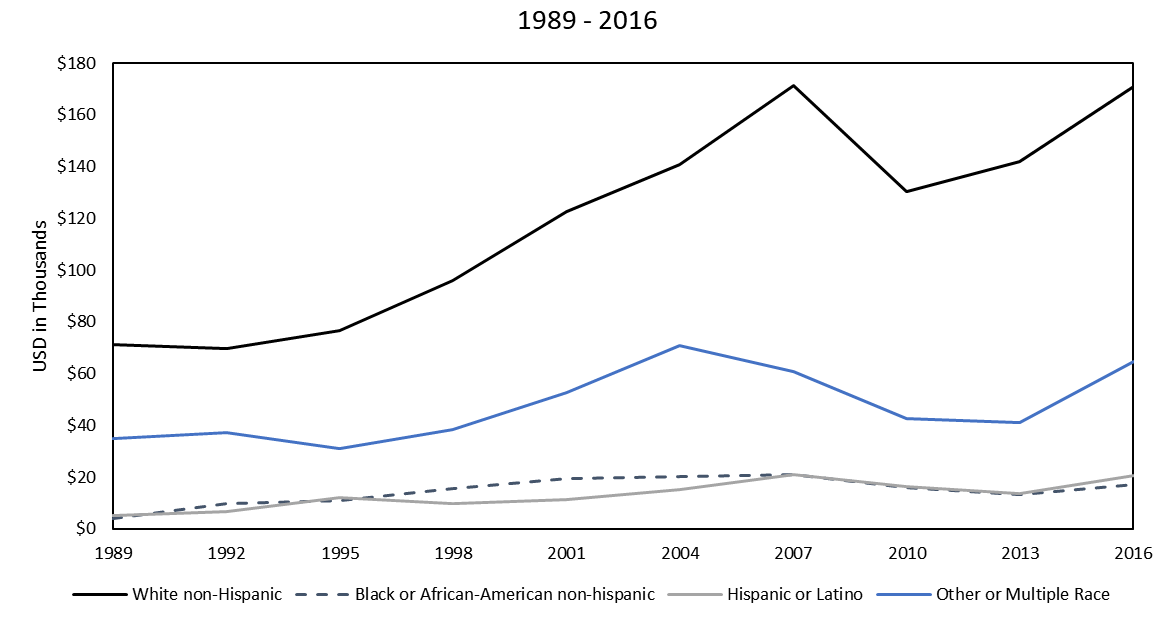

Given the declining power of education to improve economic outcomes for African Americans, persistent racial wealth gaps and the disproportionate health and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, the economic outlook for African Americans does not look promising.

But is it inevitable that COVID-19 will further entrench the devastating economic trends of the past 30 years? Or will the killings of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Elijah McClain and so many others force a fundamental reckoning of American apartheid? If this moment in history is the harbinger of fundamental change, then Black activists, business leaders, academics and policymakers all have key roles to play in re-envisioning Black economic futures.

Is it inevitable that COVID-19 will further entrench the devastating economic trends of the past 30 years?

Understanding the Racialized Economic History of the U.S. Is Critical

To generate a radically different economic future for Black communities, businesses, economies and people, some understanding of the economic history of the United States is necessary. Since the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, a common feature of government-sponsored segregation and desegregation has been an explicit intent to disadvantage African American economic success and break down Black social structures. Across the South, the de facto segregation of the antebellum Reconstruction years was not sufficiently punitive for Southern white power structures. Black communities were constantly under threat from vigilante violence as well as from state and local government intervention—often because of the success of their local economies. Black economic and political power was seen as a threat by Southern whites.

Even desegregation and urban renewal, which, in theory, should have benefitted Black communities, instead became opportunities to shutter Black schools and institutions, erode the Black professional class, disadvantage Black businesses and destroy community infrastructure. For example, the construction of Highway 147 in Durham, North Carolina during the 1960s devastated the Hayti neighborhood, displacing 500 African American-owned businesses. Similarly, Tulsa, Oklahoma’s prosperous Black Wall Street, which was rebuilt after the devastation of a 1921 race massacre, was ultimately destroyed in 1970 by a federally-funded highway project.

So what can be done to repair the long-standing damage of racial economic inequality and chart a fundamentally different path for the United States? Since March 2020, a number of diverse organizations and individuals – from activists to prominent Black scholars to public corporations – have advocated for both policy prescriptions and market-based solutions to address America’s racial divide from all angles.

Corporations Respond to Calls for Racial Equality

Some major firms have gone well beyond declarations that “Black Lives Matter” by announcing plans to use their business-to-business relationships to create new opportunities for Black-owned businesses. For example, private equity firm SoftBank announced a new $100 million Opportunity Fund for investment in companies run by people of color. Responding to Aurora James’ 15 Percent Pledge, cosmetics retailer Sephora has dedicated 15 percent of its inventory to Black-owned businesses. Vista Equity Partners CEO Robert F. Smith has challenged large corporations to invest two percent of their annual net income in Black businesses, and the NC IDEA Foundation has committed to increasing startup funding for Black entrepreneurs. Other corporations and foundations, from Nike to the Ford Foundation, have also made pledges, although not all explicitly target economic or business parity.

| 0 to 9 Employees | 10 to 99 Employees | 100 to 499 Employees | 500+ Employees | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 0.37% | 0.08% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.45% |

| Asian | 8.24% | 1.85% | 0.06% | 0.94% | 10.15% |

| Black or African American | 1.86% | 0.38% | 0.03% | 0.00% | 2.26% |

| Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander | 0.10% | 0.02% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.13% |

| White | 69.07% | 16.87% | 1.08% | 0.14% | 87.02% |

Bold Solutions Re-emerge

America’s historical attempts to disenfranchise African Americans have resulted in the disproportionate health, economic and policing impacts being experienced today by many Black communities and individuals. But it is also from this context that some of the boldest ideas for the future have gained new momentum.

The Black Belt and Baby Bonds

UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School professor Jim Johnson recently proposed a place-based federal policy solution that focuses on the Black Belt in the American South, defined in 1900 by Booker T. Washington as “the counties where the black people outnumber the white,” that stretches from southern Virginia through eastern North Carolina and across the Deep South. In his essay, Johnson outlines a comprehensive approach to “inclusive and equitable development in the region,” including increased opportunities for Black-owned businesses through diversified supply chains and more financial tools for community development. A policy designed to address generational racial wealth disparities is championed by Ohio State University Professor Darrick Hamilton. Hamilton suggests the implementation of “baby bonds,” or a race-neutral, tiered program by the federal government that would provide investment funds to all children born in the U.S.

Reparations for Descendants of Slaves

Since the abolishment of slavery, there have been successive calls for Black reparations (e.g., William Tecumseh Sherman, in Official Records of the American Civil War, Series 1, Volume 47, Part 2, 60-62;) The Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act, reintroduced into Congress every year since 1989, is receiving renewed attention. Proponents of reparations argue that the U.S. government owes compensation to the descendants of enslaved Africans for centuries of free labor. Contemporary scholars have extended the argument to include the economic impact of decades of racially discriminatory policies and their knock-on effects, such as the Homestead Act, which excluded African Americans from acquiring free land granted to more than a million white families. Jim Crow laws suppressed African American wages, home values and economic activity; “redlining” by the Federal Housing Administration intentionally prevented Blacks from owning homes. And de facto implementation of the G.I. Bill denied many African Americans access to a college education. Nearly all of these examples are still affecting Black Americans today. Scholars have provided detailed enumerations of the debt and plans for how national reparations might be executed (e.g., direct payments, baby bonds, college tuition, commercial grants, etc.). Most recently, Duke professor William “Sandy” Darity makes a case for direct payments as the primary mechanism to distribute total reparations on the order of $10 trillion. The call for reparations gained popular currency during the 2019 presidential primary season, and they continue to pervade national discussions (e.g., Asheville, NC).

Black aspirations for a collective economy

At the opposite end of the ideological spectrum from reparations are movements to build a collective Black economy that eschews federal intervention. Most historic Black towns and settlements founded by formerly enslaved people were rooted in the dream of a life and economy safe from government tyranny and vigilante violence. These places, as well as historic Black commercial districts, also proved successful in creating wealth and a Black middle class.

The desire for a collective economy has persisted within Black America despite decades of state and federal intervention. However, the social movement for Black justice has galvanized interest in efforts among African Americans to “buy Black,” “bank Black,” and recycle wealth within African American communities. While the total value of Black-owned firms is small and Black firms are being disproportionately devastated by COVID-19, they are receiving renewed interest. Scholars Julian Agyeman and Kofi Boone also suggest that “an expanded concept of the ‘Black commons’—based on shared economic, cultural and digital resources as well as land—could act as one means of redress…encouraging economic development and creating communal wealth.”

Whatever approaches are taken, this moment in history affords an unprecedented opportunity to take stock of racial economic disparities in the U.S and work together to re-envision Black economic futures.

1 See Hammond et al. (2019); Solomon et al. (2019)

2 See Ehrsam (2010)

3 Johnson et al. (2020), Booker (1901)

4 Lowrey (2020)

5 Official Records of the American Civil War Series 1, Volume 47, Part 2, 60-62

6 See Coates (2014)

7 See Martin (2020)

8 See Merritt (2016) and Frymer (2017)

9 See Aaronson et al. (2019)

10 See Katznelson (2006)

11 See Darity & Mullen (2020)

12 See Burgess, (2020)

13 See Slocum (2019) and Our Mission

14 See Fairlie (2020)

15 .eg., #BuyBlack30Challenge, #BlackOutDay2020, Beyonce’s new collaboration with BlackOwnedEverything.co; https://theundefeated.com/features/buy-black-movement-gains-international-attention/

16 See Agyeman & Boone (2020)