The Upending of Education and Childcare

Seven Forces Reshaping the Economy

As the historic 2020 U.S. presidential election approaches, the economy continues to rank as voters’ top issue – coming as no surprise given the unprecedented economic turmoil caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. In this seven-part series of Kenan Insights, we offer a current and in-depth analysis of the findings in our latest report, which explores the economic challenges and opportunities facing our nation amid and beyond both the election and the pandemic. The Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise, in partnership with the North Carolina CEO Leadership Forum, has issued Seven Forces Reshaping the Economy to help decision-makers navigate these critical trends and offer pragmatic solutions to the economic shifts that are defining our new normal. This week, we look at the upending of education and childcare.

The start of a new school year can be challenging even in normal times, with new routines, teachers and learning objectives for kids to adjust to. But this year has brought on a whole new set of worries. Students who started the school year virtually traded in their composition notebooks for iPads and bus rides for dinner tables that doubled as school desks. Others who continued to attend in-person classes faced challenging new safety protocols including practicing social distancing and wearing facing masks. It has not been an easy adjustment for students, parents and teachers alike.

With students spending more than 30 hours per week in school, not including extracurricular activities and after-school care,1 the massive changes to education delivery since the start of the pandemic have left school districts scrambling. Schools provide a host of services for students and parents — education for a range of student abilities, guaranteed childcare, access to critical educational infrastructure like computers and broadband, meal programs and more. Although this massive disruption in education will affect all, it will undoubtedly have greater consequences for some, such as low-income families, students with disabilities and working parents (mothers in particular).

The Pandemic Could Widen the Achievement Gap

The “achievement gap” refers to the longstanding disparities in academic performance or educational attainment between subgroups of students, in particular groups defined by race/ethnicity and/or socioeconomic status.2 These disparities are often measured through standardized test scores (an imperfect measure, to be sure), but can also be seen through dropout rates, college enrollment and other academic factors.

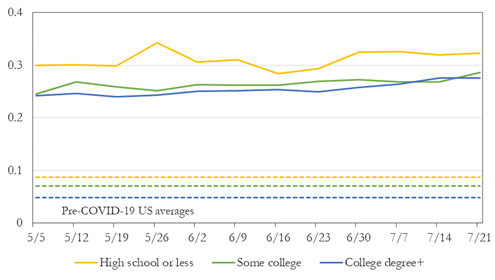

Source: Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise3

Some fear the pandemic will only exacerbate these inequities due to the ineffectiveness of current online tools and the potential decline in the number of students reached.4 In particular, access to computers and broadband may be a barrier for some, especially low-income or rural students (a phenomenon known as the “homework gap”).5 Nearly 12 million school-aged children in the U.S. live in homes without broadband access.6 Using data from Curriculum Associates, creators of the i-Ready digital instruction and assessment software, McKinsey found that only 60 percent of low-income students are regularly logging in to online instruction compared to 90 percent of their high-income peers. Additionally, engagement rates lag behind in schools serving predominantly black and Hispanic students, with only 60-70 percent logging in regularly.7 In their model, which assumes that school closures and part-time schedules will continue intermittently through the 2020–21 school year and in-school instruction will resume in January 2021, McKinsey estimates that the average learning loss for all students is seven months. However, there are larger projected learning losses for minority and low-income students, with black students falling behind by 10.3 months, Hispanic students by 9.2 months, and low-income students by more than a year.8

Students with disabilities are also at risk of falling behind. Disabled students make up 14 percent of national public school enrollment.9 This includes students with learning disabilities, speech and language impairments, physical disabilities, autism, and developmental delays, among other disabilities. Instruction for these students is often difficult to replicate in a virtual environment for a number of reasons. For example, assistive technology can be incompatible with the online tools being employed.10 In response, some states have granted provisions allowing school districts to offer some in-person special education instruction even if schools are primarily virtual.11

Childcare Burden for Working Parents

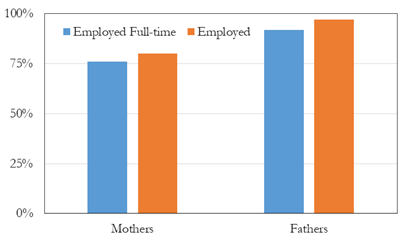

Most parents with school-aged children work, and with many students now schooling from home, working parents will have to balance their own work responsibilities while supervising and instructing their children. Many families also are experiencing financial challenges created by the economic downturn and mass unemployment. This nearly impossible balancing act will have some short- and medium-term impacts on the labor market at large — and the shock could cause long-standing implications for the career trajectories of women, who shoulder much of the childcare responsibilities. Additionally, there are roughly 15 million households headed by single mothers, accounting for 70 percent of single-parent households.12

Source: U.S. Commerce Department, Bureau of Labor Statistics

However, there may be a silver lining. Existing studies have shown that women need more flexible work schedules, and that they often prefer jobs that offer greater flexibility even if that means a pay decrease. Changing social norms around remote work and flexible hours formed during the pandemic could benefit women over time.13 14 In addition, some companies are offering benefits for emergency childcare and online tutoring of children.

Strategies to Best Meet Student and Parent Needs

More effort needs to be put into solutions that get children back to school quickly, and there is clearly a need for more robust delivery of online K-12 education. Nonetheless, schools are already integrating the lessons they have learned from operating virtually in the spring into the traditional education model. To meet student needs in a blended academic experience at a level of quality that students should expect, schools must focus their attention and resources on three key areas: technology infrastructure, strategies for effective online instruction and increased student services accessibility.

- Technology infrastructure: The shift to online education has highlighted equity gaps in access to technology and internet connectivity, among others, which will remain a challenge for both K-12 and higher education. Also, it is important that any technology employed be assessed for its capabilities for students with a range of learning, developmental and physical disabilities. Addressing broad technological challenges could have far-reaching and long-lasting positive economic and social effects.

- Strategies for effective online instruction: As many students and teachers learned this spring, simply moving a class to Zoom is not an effective replacement for the traditional classroom experience. That said, deliberate full-scale adoption of technology solutions can provide a high-value learning experience if teachers are supported and prepared with effective techniques to successfully engage students on virtual platforms. Without pedagogical support, equity gaps in student outcomes are likely to widen.

- Student services accessibility: In addition to core education, schools now have to consider carefully how students interact with broader services, including food services, counseling, college preparation, social/athletic activities and special education. The adaptations will be wide-ranging and require thoughtful planning to reimagine services and ensure access, but in many cases existing technologies can be leveraged. Additionally, such solutions will require additional person power, which could come from recent college graduates faced with a competitive job market.

1National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.). Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS). U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=76

2 National Assessment of Education Progress. (2020). Achievement Gaps. U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/studies/gaps/

3 Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise (2020). Kenan Dashboard: Reopening Amid COVID-19. https://kenaninstitute.unc.edu/dashboard/reopening-amid-covid-19/

4 Dorn, E., Hancock, B., Sarakatsannis, J., & Viruleg, E. (2020, June 1). COVID-19 and student learning in the United States: The hurt could last a lifetime. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-student-learning-in-the-united-states-the-hurt-could-last-a-lifetime

5 Vogels, E.A., Perrin, A., Rainie, L., & Anderson, M. (2020, April 3). 53% of American Say the Internet has Been Essential during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/04/30/53-of-americans-say-the-internet-has-been-essential-during-the-covid-19-outbreak/

6 U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee. (2017). America’s Digital Divide. Retrieved from https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/ff7b3d0b-bc00-4498-9f9d-3e56ef95088f/the-digital-divide-.pdf

7 Dorn, E., Hancock, B., Sarakatsannis, J., & Viruleg, E. (2020, June 1). COVID-19 and student learning in the United States: The hurt could last a lifetime. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-student-learning-in-the-united-states-the-hurt-could-last-a-lifetime

8 Dorn, E., Hancock, B., Sarakatsannis, J., & Viruleg, E. (2020, June 1). COVID-19 and student learning in the United States: The hurt could last a lifetime. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-student-learning-in-the-united-states-the-hurt-could-last-a-lifetime

9 National Center for Education Statistics. (2020, May). Students with Disabilities. U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgg.asp

10 Hill, F. (2020, April 18). The Pandemic is a Crisis for Students with Special Needs. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2020/04/special-education-goes-remote-covid-19-pandemic/610231/

11 Reid, A. (2020, July 15). IDEA at 45: How the Pandemic Affects Students With Disabilities [Blog]. NCSL. Retrieved from https://www.ncsl.org/blog/2020/07/15/idea-at-45-how-the-pandemic-affects-students-with-disabilities.aspx

12 Alon, T., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., & Tertilt, M. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality (NBER Working Paper No. 26947). Retrieved from National Bureau of Economic Research website: https://www.nber.org/papers/w26947.pdf

13 Alon, T., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., & Tertilt, M. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality (NBER Working Paper No. 26947). Retrieved from National Bureau of Economic Research website: https://www.nber.org/papers/w26947.pdf

14 Alon, T., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., & Tertilt, M. (2020). This Time It’s Different: The Role of Women’s Employment in a Pandemic Recession (NBER Working Paper No. 27660). Retrieved from National Bureau of Economic Research website: https://www.nber.org/papers/w27660.pdf