The Impact of COVID-19 on Food and Other Retailers

Seven Forces Reshaping the Economy

As the historic 2020 U.S. presidential election approaches, the economy continues to rank as voters’ top issue – coming as no surprise given the unprecedented economic turmoil caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. In this seven-part series of Kenan Insights, we offer a current and in-depth analysis of the findings in our latest report, which explores the economic challenges and opportunities facing our nation amid and beyond both the election and the pandemic. The Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise, in partnership with the North Carolina CEO Leadership Forum, has issued Seven Forces Reshaping the Economy to help decision-makers navigate these critical trends and offer pragmatic solutions to the economic shifts that are defining our new normal. This week, we look at how COVID-19 has accelerated the transformation of retailing.

Circuit City. Borders. Blockbuster. The list of large retailers declaring bankruptcy in years past is nearly a cliché for the effect of online sales on traditional retailing. Now, expedited by the COVID-19 pandemic, the list of recent bankruptcies and store closings reads like a “who’s who” of retail giants: GNC, Macy’s, Pier 1 Imports, Men’s Wearhouse, Brooks Brothers, GameStop and Bed Bath & Beyond, among others. By the end of 2020, as many as 25,000 retail stores across the United States will shut their doors for good.1

While COVID-19 has accelerated the trend of closing “big box” and chain retail locations in favor of online delivery of goods and services, some retailers, in particular food retailers (e.g., Safeway, Kroger) and chain resturants (e.g., Pizza Hut, Starbucks) have been preparing for these changes for years.

What trends are accelerating?

Retailing in general is facing massive challenges in the wake of the economic tsunami driven by the COVID-19 pandemic. The tectonic shift accelerated by COVID-19 can be categorized into four major trends:

- A shift to more online shopping across all industries and channels, including food retailing.

- Brick-and-mortar retail locations shifting in use cases and experience.

- Accelerated use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) to increase efficiency of operations, in particular for stocking decisions.

- The rise of private labels and hard-discount retailers in the United States.

We will address each of these in turn, with a focus on food retailing in particular.

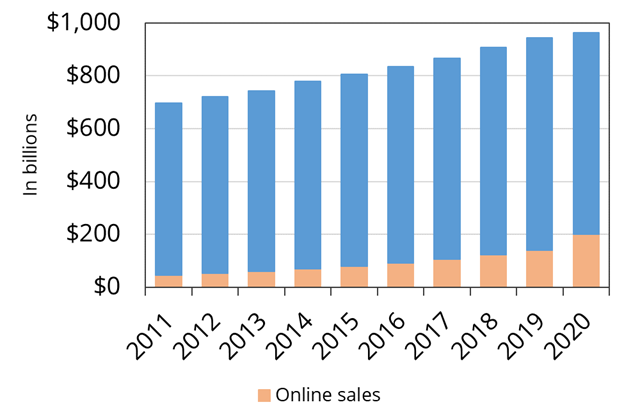

Source: Digital Commerce 360 analysis of U.S. Department of Commerce data

Online shopping can come in various forms: which ones are picking up fastest?

Online retailing has grown significantly in recent years, accelerating in 2020 in the wake of brick-and-mortar store closings related to the COVID-19 pandemic. From July 2019 to July 2020, online sales jumped 55 percent.2 For grocery retailing, the shift to online has been considerably more dramatic, and online sales growth is even more impressive. For example, Walmart’s year-over-year online sales grew by close to 100 percent, while Target’s grew by nearly 200 percent.3 Clearly, the lower the base, the easier it is to achieve such high growth rates. Indeed, a fully online experience (from online click to home delivery, much like we might get with Amazon) has always been challenging in the United States. Suburban and rural areas are less densely populated, so the economics of grocery delivery often make it impractical, including various “last mile” issues (e.g., freshness, produce and meat/fish/poultry selection) that make it more challenging than delivering nonperishables to your door.

Having known this for some time, retailers have (now successfully) been developing three groups of hybrid “click and collect” methods of delivery that minimize both the economic and “last mile” issues of fully online delivery:

- In-store pickup (buy online, pick up in store).

- Near-store pickup (curbside pickup).

- Stand-alone pickup, drive format.

We’ve all seen the first model — order online and then pick up in store, often in a locker of some sort near the store entrance with your complete order waiting for you. Curbside pickup — which Kroger has been using for years — involves ordering online and then driving up to the curbside or a specially designated lane, and having your order loaded into your car for you.

The last format is perhaps the most interesting and innovative, taking a cue from France’s Drive and other European initiatives.4 Here, stand-alone locations and kiosks are designated as pickup locations. These locations are not necessarily on site at the grocery retailer’s physical location, but rather might be placed around town for quick pickup (e.g., gas stations).

Academic research (Gielens et al., 2020) suggests that all three “click and collect” (“C&C”) models boost a retailer’s online sales, acting to increase primary demand rather than cannibalize existing sales.5 In addition, research on the “C&C” format suggests that:

- In-store pickup works well for larger households that buy more perishables and impulse items.

- Stand-alone pickup works well for shoppers with high collection-convenience needs, e.g., those buying bulky and large items, and rural and weekend shoppers seeking convenience.

- There are often positive spillover effects for brick-and-mortar sales, resulting in increased profits.

These trends will increase in a post-COVID-19 environment as shoppers have become comfortable with the “click and collect” experience.

Implications for brick-and-mortar stores

As noted earlier, thousands of brick-and-mortar stores will close in 2020, but this is not a new trend. In 2019, almost 10,000 retail locations closed.6 The flood of store closures has been led largely by “big box” stores and clothing retailers. While COVID-19 may have accelerated the closure of those stores already on their way out, it allowed remaining stores to emerge stronger. Some scholars, including Scott Galloway, marketing professor at New York University, have criticized the CARES Act for favoring online retailers and larger mass discounters, such as Walmart and Target, who were able to stay open during the pandemic. Ultimately, however, grocery retailing needs physical footprint and hence will survive many of the changes we are currently experiencing.

This said, the shift to an increasing focus on convenience will only continue. Specifically, we will likely see a surge in convenience store growth (7-Eleven, for example, recently took over more than 3,900 gas stations from Marathon).7 Convenience stores may be particularly well suited for the post-COVID world, as consumers have shifted their restaurant expenses almost exclusively to grocery retailing. While the pendulum will almost certainly swing back to restaurants, it is unlikely that it will do so completely anytime soon. More generally, convenience options (e.g., meal kits) and convenience stores will likely benefit from this trend and reap the lion’s share of the shift in consumer spend. To provide evidence and context, this is already happening in Europe, where convenience stores have been rising steadily. In Norway, for example, almost all grocery retailers are convenience stores.

For a broader discussion of the impact on COVID-19 on retailing, view the Kenan Institute webinar “How Can Retail Survive COVID-19?”

The role of machine learning on stocking levels

In retailing, assortment strategy involves the number and type of products that stores display for purchase by consumers. To manage costs, retailers want to reduce assortment size while balancing the push for new products by manufacturers. One way to cut costs is for retailers to have wide SKU facings with limited assortment — a tactic Walmart uses. The European Union, however, has contemplated actions against large retailers for this policy — arguing that a smaller number of SKUs with larger facings for each SKU limits innovation and consumer choice.

A potential alternative for both consumers and retailers is for automated assortment decisions to be made through machine learning (ML). Employed in a variety of industries, ML attempts to automatically adjust stock levels to customer demand. While ML techniques have not been widely employed in food retailing, the COVID-19 pandemic is changing that.8 Supply chain pressures have forced manufacturers and retailers alike to reduce assortment size in order to increase overall category profitability.9 10 ML techniques can be extended to food retailing to balance the need to lower costs and increase profitability while maintaining SKU variety (as per the EU concern noted above). This may indeed be the push that is needed to use ML to bring about assortment size reductions efficiently. One major downstream benefit might be even more personalized sales promotions, consumer-specific price cuts and so on, to the benefit of both consumers and retailers.

Private labels and hard discounters on the rise

Retailer-owned products, known as private labels, are often cheaper than their national-brand equivalents. Historically, U.S. private labels have suffered from quality issues — both in reality and in terms of consumer perceptions. However, today these labels are often comparable in quality and value. Hard discounters such as Aldi or Lidl, whose private-label brands account for more than 80 percent of their SKUs, have been a constant and growing threat to traditional food retailers in the United States.

For private labels and hard discounters, success and growth are heavily tied to the aggregate economy.11 12 In recessions, both typically take off and grow quickly. Because of budget constraints, consumers are forced to shift partly to private labels or to hard discounters, and once they learn that they are “good enough” or an even better value, they typically do not go back to the higher-priced national brands completely. This allows for sustained growth of private labels and hard discounters during recessions.

However, in a bit of a trend anomaly, high-priced premium private labels with extremely high quality outgrew national brands by a factor of three in the past few years, which was a period of unprecedented economic growth. The impact on food retailers is significant. A recent white paper by Gielens (2020) has shown that the rise of hard discounters (who often have prices that are as much as 40 percent cheaper than competitors) leads to enormous pressure on prices and reductions up to 15 percent across all products.13

The COVID-19 pandemic may push private label and hard discount growth to unprecedented levels. First, given that the pandemic has driven wide swaths of the economy to fall to unemployment and bankruptcy, we would expect a shift to value-focused, cheaper private labels and hard discount retailers to increase through 2021.14 Indeed, Lidl has recently announced it will invest more than $500 million to grow its U.S. retail store base by 50 percent and create more than 2,000 jobs by the end of 2021. Second, many consumers have stopped going out, and restaurant-related expenses have dropped drastically. Yet these consumers still crave “restaurant-like” meal quality, and higher-priced premium private labels may be particularly well positioned to cater to these needs.

Wrapping up — accelerating trends

There is an old proverb that says, “May you live in interesting times.” Whoever said this surely did not have 2020 in mind, but the COVID-19 pandemic has been described again and again as “unprecedented,” “once in a lifetime,” and “interesting times.” For retailers who were unprepared for the tectonic shift the pandemic has brought, the impact has been devastating. For those, like grocery retailer Kroger, who had already been preparing for the shift for years, this acceleration of trends has presented an opportunity — to increase the efficiency of operations through AI and ML, to implement “click and collect” methods that stimulate primary category demand, to shorten the format of what “brick-and-mortar” means, and to shift to private label brands that can generate higher margins. There are valuable lessons here — lessons from which retailers in nongrocery categories may learn. Such lessons may indeed be the key to the survival of retail in 2021 and beyond.

For additional analysis of the transformation of retailing, including segments beyond the grocery industry, view our research report, Seven Forces Shaping the Economy.

This article is based in large part on the webinar “COVID-19: Accelerating Trends in Food Retailing,” July 1 2020, Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise). We thank Jody Kalmbach, Group Vice President of Product Experience at Kroger and Mark Baum, Senior Vice President of Industry Relations and Chief Collaboration Officer at FMI, for their insights for this article.

1 Whiteman, D. (2020, August 12). These Chains Are Permanently Closing the Most Stores in 2020. Moneywise. Retrieved from https://moneywise.com/a/chains-closing-the-most-stores-in-2020

2 Redman, R. (2020, August 18). Omnichannel efforts lift Walmart in second quarter. Supermarket News. Retrieved from https://www.supermarketnews.com/retail-financial/omnichannel-efforts-lift-walmart-second-quarter

3 Redman, R. (2020, August 19). Target Q2 sales jump more than 24% overall and 195% in digital. Supermarket News. Retrieved from https://www.supermarketnews.com/retail-financial/target-q2-sales-jump-more-24-overall-and-195-digital

4 Wells, J. (2017, July 20). Report: France’s Drive is a growth model for U.S. grocery e-commerce. Grocery Dive. Retrieved from https://www.grocerydive.com/news/grocery–report-frances-drive-is-a-growth-model-for-us-grocery-e-commerce/534893/

5 Gielens, K. et al. (2020). Navigating the Last Mile: The Demand Effects of Click and Collect Order Fulfillment. [Working paper].

6 Lawless, S. (2019, December 23). More than 9,300 stores are closing in 2019 as the retail apocalypse drags on — here’s the full list. Business Insider. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/stores-closing-in-2019-list-2019-3

7 Wong, J. (2020, August 3). 7-Eleven’s $21 Billion Deal Could Be a Marathon. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/7-elevens-21-billion-deal-could-be-a-marathon-11596451820

8 Dekimpe, M. G. (2020). Retailing and retailing research in the age of big data analytics. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 37(1), 3-14. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2019.09.001

9 Sloot, L. M., Fok, D., & Verhoef, P. C. (2006). The Short- and Long-Term Impact of an Assortment Reduction on Category Sales. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(4), 536-548. doi:10.1509/jmkr.43.4.536

10 Sloot, L. M., & Verhoef, P. C. (2008). The Impact of Brand Delisting on Store Switching and Brand Switching Intentions. Journal of Retailing, 84(3), 281-296. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2008.06.005

11 Lamey, L., Deleersnyder, B., Dekimpe, M. G., & Steenkamp, J. E. (2007). How Business Cycles Contribute to Private-Label Success: Evidence from the United States and Europe. Journal of Marketing, 71(1), 1-15. doi:10.1509/jmkg.71.1.001

12 Lamey, L., Deleersnyder, B., Steenkamp, J. E., & Dekimpe, M. G. (2012). The Effect of Business-Cycle Fluctuations on Private-Label Share: What has Marketing Conduct Got to do with it? Journal of Marketing, 76(1), 1-19. doi:10.1509/jm.09.0320

13 Gielens, K. (2020). The Impact of Lidl’s Entry on Grocery Prices in Long Island, New York. [White paper]. Commissioned by Lidl.

14 Redman, R. (2020, August 25). Lidl powers up U.S. expansion with another 50 stores. Supermarket News. Retrieved from https://www.supermarketnews.com/retail-financial/lidl-powers-us-expansion-another-50-stores