Venture-backed vs. Main Street: A Widening Business Gap

COVID-19 has affected entrepreneurial funding in ways that will shape the economy for years to come. As businesses begin to look past the pandemic, a stark contrast in access to external capital is emerging. Although venture capital funding is extremely robust, many main street businesses face questionable futures as government support programs wind down. For both high-tech and main street businesses, the pandemic hit underserved communities and minority-owned businesses especially hard.

In this Kenan Insight, we examine the entrepreneurial funding trends detailed in the 2021 Trends in Entrepreneurship Report; the forces creating the haves and have-nots in this new economic climate; and potential policy remedies.

Venture-backed Business Boomed…

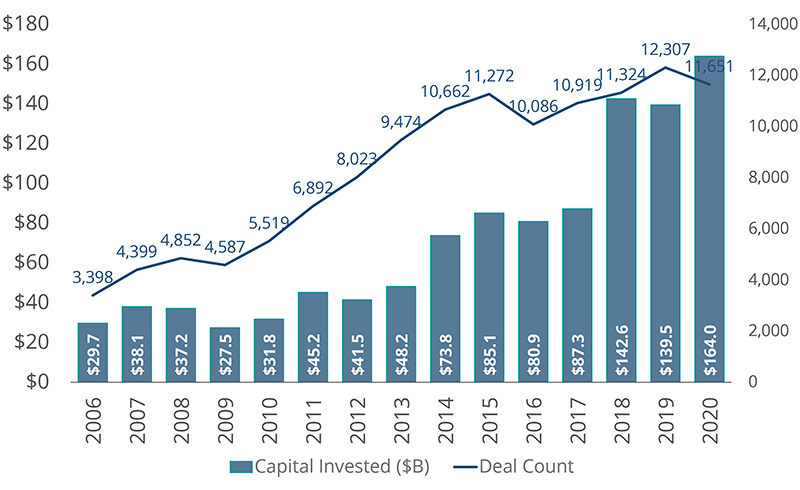

During the pandemic, venture capital investments continued almost as though nothing had happened. In fact, 2020 was a landmark year for venture capital. The number of deals and rates of funding remained robust, with 2020 funding dollars reaching a new all-time high.1 Additionally, this activity was strong across all deal flow stages – seed/angel, early-stage and late-stage.

Boom: VC Deal Activity Remains Very Strong

One reason that venture remained strong, is that many of the types of companies raising money did not face the inherent problems that the pandemic caused for more mainstream, consumer-facing businesses. Tech companies were not only able to continue developing their business even with employees working virtually – but many companies got a boost from increased digital use during the pandemic. In particular, the lockdowns and travel restrictions of 2020 meant that workers and consumers were more reliant on tech services such as video conferencing and online shopping, benefiting many tech companies.

Halfway through 2021, and all indication is that venture capital is going to continue to reach new heights. According to the NVCA/Pitchbook Venture Monitor for Q2, 2021 is on track to be venture capital’s best year yet, with $150bn in VC dollars already deployed to high-growth startups.2

But Small Businesses Were Hit Hard

The story is much different for many main street businesses. From around January 2020 to April 2021, small business sales figures dropped 20% or more. Businesses in high-income zip codes tended to be hit harder during this time. This is likely because businesses in these areas tend to provide non-essential services to business clientele, or because consumers in these areas could more easily substitute online delivery for going to the store.

For many small businesses, government programs such as the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) was the primary aid that kept them afloat during COVID-19. Although this funding was essential, it may be difficult for these businesses to transition to other sources of capital as PPP and other programs have ended in recent months. Additionally, even as the vaccine ushered in new hope for re-opening, the rise of the delta variant and stagnant vaccination rates has caused more uncertainty. For these reasons, we likely still have not seen the full economic consequences of the pandemic yet.

According to the Office of the Advocate for Small Business Capital Formation Annual Report for Fiscal year 2020, 70% of small businesses are concerned about financial hardship due to prolonged closures, and 58% worry about having no choice but to permanently close.3 Now, as many businesses start to re-open, there are new challenges. In particular, small businesses have greater competition for attracting and retaining workers in the tight labor market especially for low-skill jobs which have rebounded significantly in recent months . According to the National Federation of Independent Business’s monthly jobs report, 46% of owners reported job openings that could not be filled, which is well above the 48-historical average of 22%.4 Additionally, global supply chain disruptions have caused shortages and prices spikes for a wide variety of goods . The struggles these small businesses face will most likely have long-term consequences for the economic resilience of many areas of the country.

Business Formation Takes Off – But Out of Necessity?

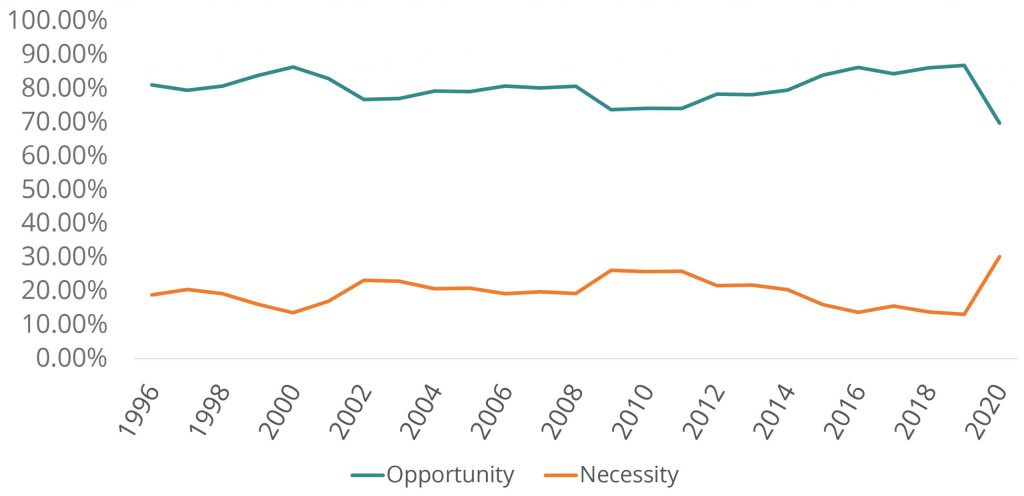

An additional potential bright spot in the overall bleak year for business in 2020, was that new business formation was the highest it has been in more than 15 years.5 There was a spike for both high growth potential and other new businesses. This growth in business formation occurred throughout the United States, and among a wide array of industries. Fortunately, the trend has continued through 2021 with only a slight recent tapering.6

Nonetheless, it is important to recognize that some of this growth in business formation is due to necessity entrepreneurship as more workers were displaced during the pandemic. According to the Kauffman Foundation, the rates of necessity entrepreneurship rose sharply in 2020, and rates of opportunity entrepreneurship experienced a 25-year low.7

Opportunity vs. Necessity Entrepreneurs

In a working paper comparing business application trends between the Great Recession and the COVID-19 recession, Dinlersoz et al. (2021) find that during the Great Recession, business applications fell slowly but persistently. During the pandemic, on the other hand, business applications experienced a sharp V-shaped dip and recovery. Notably, the composition of these applications shifted significantly toward firms most likely to be non-employer businesses relative to new employer businesses.8

At first glance, the business formation data looks positive, but it comes with some caveats that should not be ignored. Only time will tell if dividends pay off from this increased startup activity, or if this is a short-term response to a historically uncertain time.

Women and Minority Business Owners Hit Harder

In addition to the overarching disparities in funding for high tech verses main street businesses, there are also inequalities within these groups. Even before the pandemic, women and minority-owned business founders faced challenges in accessing resources. The pandemic has only widened these wealth gaps. For example, despite an overall rise in venture capital investments, the deal value of venture capital funding dropped by about a third for female-founded start-ups in 2020.

For small businesses, women and minority owners were forced to shut their doors more often than their male and white counterparts in the early months of the pandemic. From February to April 2020, 3.3 million (22%) of all small businesses had to close.9 Among businesses owned by African Americans, that number was a whopping 41%. Nearly one-third of Latino-owned businesses closed, as did over one-quarter of businesses owned by women or by Asian Americans.

Although PPP helped keep many businesses going, the way it was distributed—especially in the first round– may have contributed to these disparities. Banks played an important role in deciding who received PPP support, which meant that some funds initially flowed to regions that were less adversely affected by the pandemic. One study found that the value of loans received by Black-owned businesses amounted to only about 50% of those received by similar white-owned businesses.10 However, this effect was not as persistent as changes in the PPP program were implemented in the second round.

Monitoring Trends Through 2021

For many reasons, 2020 was an unprecedented year. The trends in entrepreneurial funding were no different: on one end of the spectrum, there was historic capital growth for high growth tech startups, and on the other, small businesses closed at alarming rates due to the pandemic. As these trends continue to persist into 2021, industry and policy leaders alike will be carefully watching for the long-term implications of a number of shifts, from the changing makeup of Main Street to the increased digital reliance of consumers and workers. This time is both fraught with challenges but also holds a glimmering hope of opportunity.

The 2021 Trends in Entrepreneurship Report, including insights on emerging technology in the healthcare industry, inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystems and trends in human capital, is available for download.

Have cutting-edge research you’d like featured in our 2022 Frontiers of Entrepreneurship conference and Trends in Entrepreneurship report? Learn more and submit by September 24 for consideration!

1 National Venture Capital Association. (2021) NVCA 2021 Yearbook. https://nvca.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NVCA-2021-Yearbook.pdf

2 Pitchbook & National Venture Capital Association. (2021). Venture Monitor Q2 2021. https://nvca.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Q2_2021_PitchBook-NVCA_Venture_Monitor-1.pdf

3 U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. (2020). 2020 OASB Annual Report. https://www.sec.gov/reports-and-publications/annual-reports/2020-oasb-annual-report

4 Labor Shortage Remains a Challenge for Small Businesses as Inflation Increases. (2021, July 13). National Federation of Independent Business. https://www.nfib.com/content/press-release/economy/labor-shortage-remains-a-challenge-for-small-businesses-as-inflation-increases/

5 United States Census Bureau. (2021). Business Formation Statistics. [Data file]. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/econ/bfs/index.html

6 United States Census Bureau. (2021). Business Formation Statistics. [Data file]. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/econ/bfs/index.html

7 Fairlie, R. & Desai, S. (2021, February). National Report on Early-Stage Entrepreneurship in the United States: 2020. Kauffman Foundation. https://indicators.kauffman.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/03/2020_Early-Stage-Entrepreneurship-National-Report.pdf

8 Dinlersoz, E., Dunne, T., Haltiwanger, J. & Penciakova, V. (2021, January). Business Formation: A Tale of Two Recessions (CES 21-01). U.S. Census Bureau. https://www2.census.gov/ces/wp/2021/CES-WP-21-01.pdf

9 Office of the Advocate for Small Business Capital Formation Annual Report for Fiscal Year 2020. (2020). U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. https://www.sec.gov/files/2020-oasb-annual-report.pdf

10 Atkins, R., Cook, L., Seamans, R. (2021). Discrimination in Lending? Evidence from the Paycheck Protection Program. SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3774992