The Global-K Recovery

The 2020 U.S. economic downturn fueled by the COVID-19 pandemic generated both big losers (such as restaurants and the hospitality sector) and big winners (such as high tech and online retail), leading economic commentators to call the recession “K-shaped.” As the pandemic evolves in 2021, this K-shaped recovery will go global; though some countries, notably the U.S. and China, are securely tethered to the largest economic booster rocket ever built, a sizable swath of the world will continue to suffer weak growth.

In this analysis, we’ll explore how the global K-shaped recovery will affect U.S. businesses and households.

What’s driving the U.S. economy?

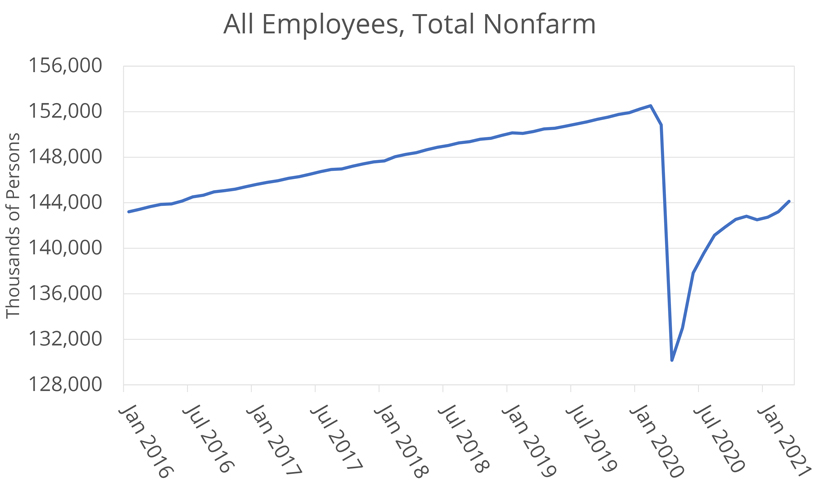

The March U.S. employment report reveals that the economy is normalizing more rapidly than expected. An increase in payrolls (916,000) exceeded forecasts, but more important, strong gains in such sectors as restaurants, hotels, transportation and construction suggest that growing optimism over a light at the end of the pandemic tunnel is being reflected in business hiring. Although the U.S. still needs to generate 8 million jobs to return to February 2020 employment levels, the pool of unemployed workers still seeking jobs continues to decline. The result is a U.S. unemployment rate that has dipped to 6.0% — just slightly above the long-run average. As the pandemic wanes and the economy continues to recover, many workers who have exited the labor force will return to work, which will drive total employment back toward pre-pandemic levels over the next year. These rapid gains in employment are self-reinforced as workers generate disposable income that feeds more spending and job growth.

But is the downturn really over? Or, put another way, can we be confident that a fourth wave of the pandemic won’t quash the rebound, as second and third waves did in 2020?

We believe we can be. It appears that the U.S. has turned the corner and pandemic-related constraints on the domestic economy will end in the second and third quarters. The game-changing vaccines now being rapidly administered will allow us to reach a critical level of immunity in the late spring or summer . This will provide businesses and the general public the confidence they need to resume pre-pandemic activities.

As we’ve been saying for almost a year, nonessential activities away from home should be governed by healthcare capacity. With high vaccination rates among those most likely to contract a severe case of the virus, the burden on the healthcare system will continue to decline and stay well below critical levels. When viewed in this light, vaccine dissemination remains the single most important government stimulus effort.

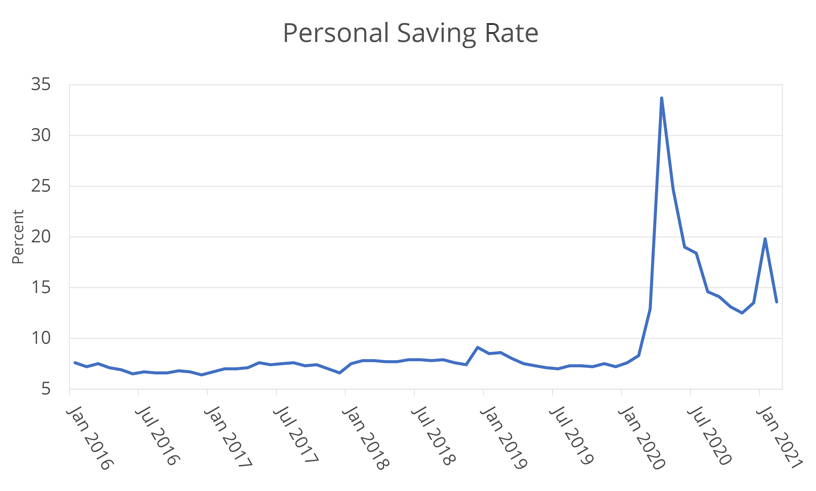

The transition back to a more normal world will release unprecedented pent-up demand for items ranging from leisure travel and entertainment to business investments. Over the past year, many households have amassed substantial savings and financial gains from asset appreciation that will fuel an enormous spending spree. In addition, businesses are awash in cheap capital that will be unleashed on capital expenditures to support the spike in demand.

But vaccination rates are by no means the only factor at work. The U.S. government has also distributed an unprecedented number of stimulus dollars. In addition to the 2020 stimulus payments, the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 will generate fresh demand, creating a powerful second-stage booster to an economy that has already blasted off. Further fiscal expansion (such as the Biden administration’s proposed infrastructure plan) could generate even more thrust.

The government’s extremely accommodative monetary policy also provides powerful fuel for economic growth. The Federal Reserve continues to signal a lack of trepidation about an overheating economy, and will maintain its unparalleled push to keep rates low for an extended period.

All of this signals boom time in America, with an expectation that 2021 will usher in one of the largest GDP growth rates on record. We should note that there are very real questions concerning the implications of such federal support on inflation and government debt capacity. But the upward trajectory of the U.S. economy — an important component of the upper branch of the K-shaped recovery — is not in doubt.

The global economy

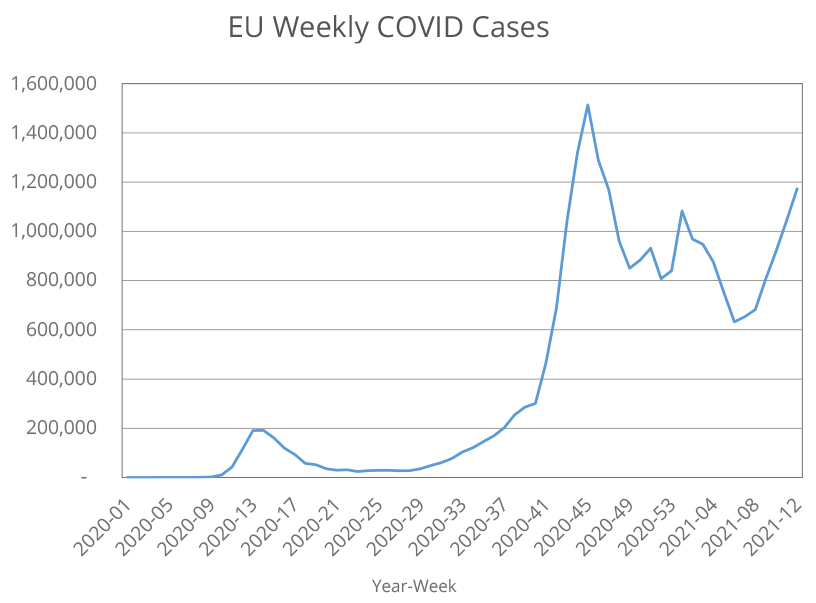

Unfortunately, such forces are not at work uniformly across the globe. Many large economies are well behind the U.S. in their vaccination rates. Numerous developed countries, particularly those in western Europe, have experienced significant increases in COVID cases in recent weeks, accompanied by new economic restrictions as vaccination efforts have faltered. Large developing economies such as India and Brazil are not expected to have substantial vaccination levels until well into 2022. Fiscal and monetary policies will be less successful in these countries because they will be powerless to effectively stimulate restricted parts of the economy, and business investment there will continue to languish as capital is diverted to economies that can normalize business activity (and are thus more productive).

As a result, a substantial part of the global economy will find itself in the lower branch of the K-shaped recovery. The economic and social costs of the pandemic will linger in parts of the world for far longer than in the U.S. and China. Unequal vaccine access will translate into critical differences in economic recovery rates, with less developed countries recovering much less quickly than their more developed counterparts from the pressures of the pandemic.

What does the global K-recovery mean for U.S. businesses?

As we’ve already noted, the business sector in the U.S. will boom in 2021 on the back of rapid domestic demand from consumers, with the industries most affected by the pandemic recovering quickly. In turn, this growth will generate spillover demand to all industries, even those that have benefited from the pandemic.

Although this is great news for the economy, it will also generate two important challenges. First, many businesses in the U.S. will experience labor shortages. With more than 5 million people exiting the labor force in 2020, some industries have already struggled with staffing. The March Beige Book survey of U.S. businesses by the Federal Reserve found “labor supply shortages were … acute among low-skill occupations and skilled trade positions.” As the economy gains speed, these shortages will become more severe and especially challenging for small businesses, which are historically less likely to be competitive in tight labor markets (and currently in worse financial shape, on average).

The second major challenge is the fragile global supply chain. We’ve seen throughout the pandemic how U.S. business operations have been disrupted by long and thin supply chains. These problems have not been resolved and are getting worse in some sectors. For example, supply constraints for semiconductors are negatively affecting production of an increasingly wide variety of consumer and capital goods ranging from automobiles to automated machine tools. With many businesses experiencing simultaneous constraints on labor and capital, it will be hard to manage the impacts through traditional means, such as substitution of one factor for the other.

What does it mean for U.S. households?

Is a massive economic boom good news for U.S. households? It’s great news for those most negatively affected by pandemic shutdowns. Laborers and sole proprietors in the most distressed industries will be in high demand, as many workers have shifted out of those jobs or left the work force in 2020. Wage growth overall will be strong in 2021, and low-skilled workers in particular will see strong upward wage pressures and improvements in benefits as companies compete for increasingly scarce labor (and try to entice those who have left the labor force into returning).

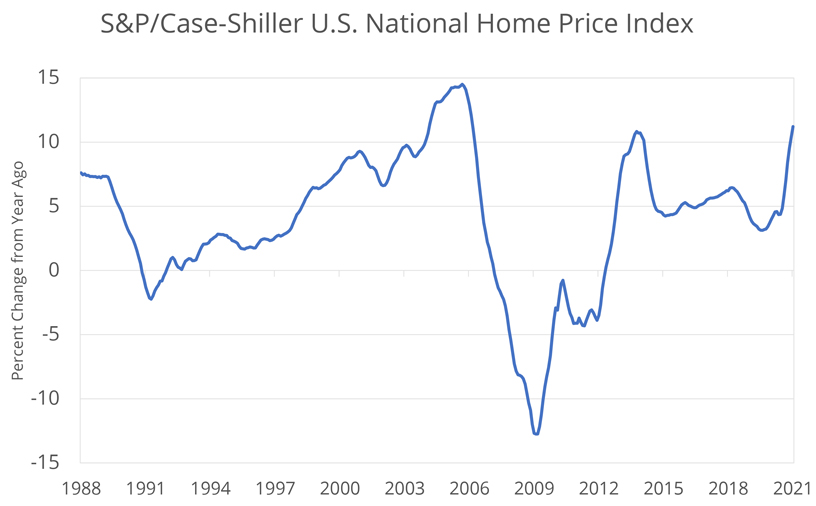

But the boom will create challenges for households as well. Most concerning is the possibility of higher inflation, as demand starts to exceed supply in certain sectors. This is most evident in housing, where home prices have already shot up at their highest rate since 2006 and rents in some regions also have spiked. While this is good news for homeowners, it’s an added burden to renters and households who are first-time home buyers — exactly, on average, the households disproportionately affected by the 2020 downturn. Likewise, many consumer goods will experience inflationary pressures on high-demand and supply challenges, which will also most affect households with low disposable income (because goods are a higher percentage of their expenditures). The roadmap for inflation remains one of the most important issues for a post-pandemic U.S. economy.

Another challenge facing many lower-income households will be overcoming the scarring of their balance sheets and credit ratings. Those who lost work and accumulated new debts during the pandemic will benefit less from the return to normal as loan and rent forbearance ends. Such households overlap substantially with those that had low net assets prior to the pandemic. Although they will end 2021 better off than at the start of the year, their gains will be less, on average, than those of wealthier households who more likely maintained employment in 2020.

A final challenge for households will be managing permanent shifts in the economy. The pandemic accelerated an existing trend toward jobs requiring certain skills (especially technical skills). Younger workers will more likely be hired and/or trained for these new jobs, while many middle-aged and older workers will struggle to find opportunities for upskilling to advance their careers. It’s likely that the shift in skills demanded by the labor market will create near-term frictions that temporarily increase the equilibrium unemployment rate, i.e., NAIRU — the nonaccelerating inflation rate of unemployment. This bump in NAIRU further increases inflation risks to households.

The bottom line

Although U.S. economic growth in 2021 is shaping up to be among the best in decades, both businesses and households will face some challenges. Lower-income households should stand to benefit the most from a strong economy, but after a brutal 2020, many will remain worse off than before the pandemic. Yet there is still time to consider how to more evenly share the benefits of growth as the global economy catches up. For example, in addition to high domestic demand for capital goods and industrial facilities, the U.S. will discover more opportunities to export high-value goods and services. Policy can provide additional incentives to encourage low-skilled workers to prepare for these opportunities that will be in high demand in coming years.